The causal role of a gene is interrogated by experimentally perturbing its function, often using interventions that produce strong protein knockouts. However, biological systems possess complex quantitative dynamics, with strong knockdowns being less informative than more subtle, quantitative perturbations.

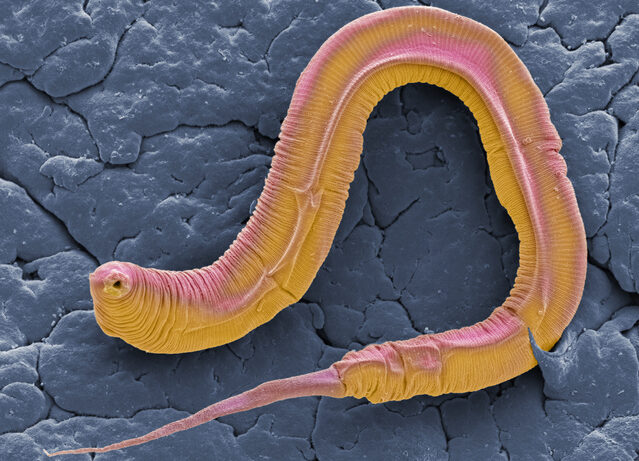

In a new study published in Nature Communications titled, “Engineering the auxin-inducible degron system for tunable in vivo control of organismal physiology,” researchers from the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and the University of Cambridge have leveraged the auxin-inducible degron (AID) system to tune protein levels with precision in the model worm, Caenorhabditis elegans. The advance has applications in uncovering the molecular underpinnings of aging and disease.

The AID system evolved in plants as a mechanism through which the hormone auxin regulates proteins required for growth and development and possesses many practical advantages over other methods, including rapid and reversible degradation. Notably, the involvement of an easily-deliverable, small-molecule activating compound makes the AID system a particularly promising technology for quantitative control over protein abundance in vivo.

“No protein acts alone. Our new approach lets us study how multiple proteins in different tissues cooperate to control how the body functions and ages,” said Nicholas Stroustrup, PhD researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation and corresponding author of the paper.

The lack of precise, lifelong, tissue-by-tissue control has been a bottleneck to understanding how subtle molecular changes impact an entire organism over time. The new method has implications for studying whole-body, systemic processes, such as aging, that are shaped by interactions across different organs.

“To unpick nuance in biology, sometimes you need half the concentration of a protein here and a quarter there, but all we’ve had up till now are techniques focused on wiping a protein out. We wanted to be able to control proteins like you turn the volume up or down on a TV, and now we can now ask all sorts of new questions,” explained Stroustrup.

The AID system identifies a protein with a degron tag for recognition by TIR1 for degradation when auxin is present. The researchers genetically engineering worms to produce a TIR1 enzyme in specific tissues only. When the worms are fed auxin-containing food, TIR1 is activated, causing the cell to remove the appropriate amount of protein. The technique allows scientists to control how much of a protein remains, where in the body it is controlled, and when the change happens while the worm continues its normal living functions.

Notably, the study combined two different TIR1 enzymes, each triggered by a separate auxin compound. By placing the system in separate tissues, the researchers independently controlled the same protein in the worm’s intestine and neurons or controlled two different proteins at the same time

“Getting this to work was quite an engineering challenge. We had to test different combinations of synthetic switches to find the perfect pair that didn’t interfere with one another. Now that we’ve cracked it, we can control two separate proteins simultaneously with incredible precision. It’s a powerful tool that we hope will open up new possibilities for biologists everywhere,” said Jeremy Vicencio, PhD postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation and first author of the study.