Artificial intelligence systems for diagnosing cancer from pathology slides often vary in accuracy according to a patient’s age, race and sex, researchers report.

The findings, in Cell Reports Medicine, stress the need to check for bias in these data-driven algorithms to ensure they enhance diagnostic accuracy even when overall performance appears strong.

The AI issues may have been due to underrepresented patients in training sets, differences in disease incidence, or subtle molecular variations between different demographic groups.

“We found that because AI is so powerful, it can differentiate many obscure biological signals that cannot be detected by standard human evaluation,” explained researcher Kun-Hsing Yu, PhD, from Harvard Medical School.

The results have led the researchers to develop Fairness-aware Artificial Intelligence Review for Pathology (FAIR-Path), a machine learning framework that mitigates around 90% of bias through a fairness-aware contrastive learning process.

Several studies have previously demonstrated the ability of AI to detect tumors, cancer subtypes, predict cancer-related genomic profiles, and estimate patient survival.

But bias remains a significant challenge, with large-scale pathology datasets predominantly consisting of Caucasian patients that can introduce bias into training sets and is subsequently reflected in diagnostic models.

To investigate the extent to which this might occur, the team performed a systematic fairness analysis in computational pathology that evaluated critical cancer detection and classification tasks across 20 cancer types and eight datasets.

The study involved 28,732 whole-slide cancer pathology images from 14,456 cancer patients, encompassing 20 cancer types across five medical centers and three nationwide study cohorts.

The analysis revealed that standard deep learning models exhibited biases, with performance disparities in 29.3% of diagnostic tasks across demographic groups defined by self-reported race, gender, and age.

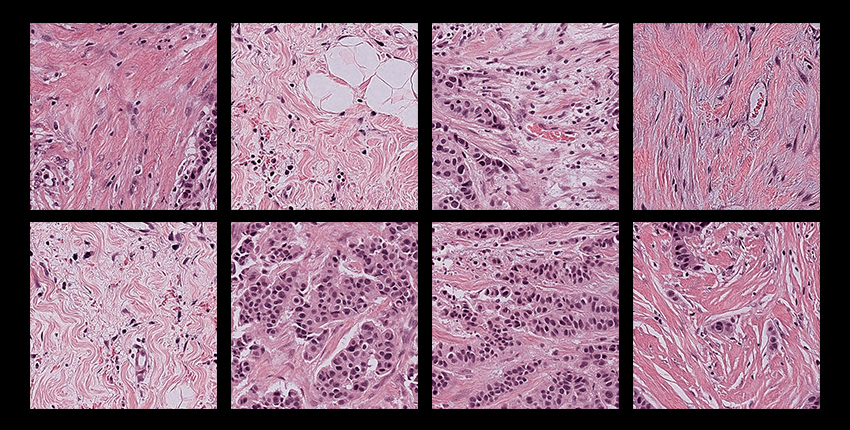

The team found that differences in tumor histology linked with different demographic groups were detectable by AI models.

Specifically, it appeared that morphological variations associated with demographic factors are embedded in tissue architecture and can be inadvertently internalized by AI models.

In older patients, for example, tumors consistently showed increased stromal volume and diminished inflammatory infiltration compared to younger patients.

Tumors from African American patients show a higher density of neoplastic cells and a lower presence of immune and stromal components compared to those from Caucasian patients.

Applying the FAIR-Path framework mitigated 88.5% of the disparities, with external validation revealing a 91.1% reduction in performance gaps across 15 independent cohorts.

“AI models can encode representation biases from demographically imbalanced pre-training datasets, and their downstream training is vulnerable to shortcut learning—a risk that persists regardless of the feature encoder’s representational power unless fairness constraints are explicitly applied,” the researchers reported.

But they added: “By incorporating fairness-aware contrastive learning, our FAIR-Path framework substantially mitigated these performance gaps across a wide range of pathology evaluation tasks in diverse external cohorts.

“This enhanced fairness in AI-driven pathology models will lead to more equitable diagnostic assessments, reducing the risk of misdiagnosis and enhancing patient outcomes.”