Hyperphosphorylated tau, the protein that makes up the tangles observed in tauopathies like Alzheimer’s disease, may be the consequence of an antiviral mechanism intended to protect the brain from infections. That’s according to new research analyzing tau’s microbial activity against herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) performed by scientists at Mass General Brigham (Mass Gen) and their collaborators at Harvard University and elsewhere.

Full details are provided in a new Nature Neuroscience paper titled “Phosphorylated tau exhibits antimicrobial activity capable of neutralizing herpes simplex virus 1 infectivity in human neurons.” The findings support an idea that Rudolph Tanzi, PhD, the paper’s senior author and director of the McCance Center for Brain Health and Genetics and Aging Research Unit in the neurology department at Mass Gen, and his colleagues have been interested in studying. That idea being that people with genes that predispose them to Alzheimer’s pathology may once have had a survival advantage against widespread infection when humans lived for 30 years or less. But as lifespan increased, those once protective mutations increased susceptibility to Alzheimer’s.

Considering the findings from this research alongside the group’s earlier work showing that “amyloid beta, the main component of senile plaques, is an antimicrobial protein, we believe Alzheimer’s pathology may have evolved as an orchestrated host defense system for the brain,” Tanzi said.

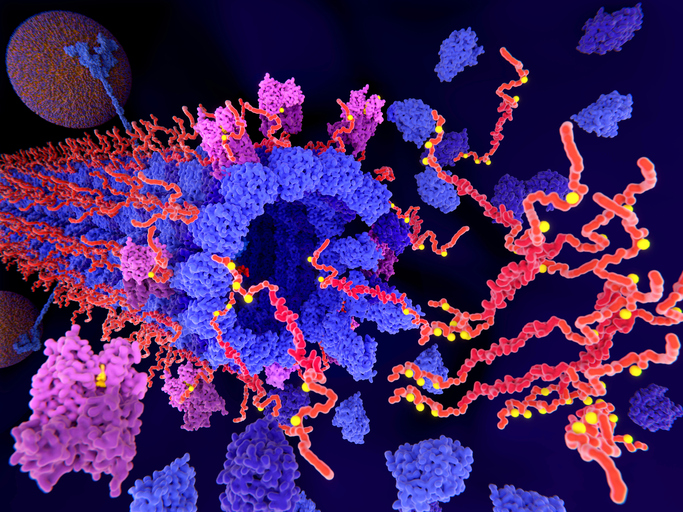

Specifically, “our data suggest that the ‘pathogenic’ characteristics of tau hyperphosphorylation, microtubule destabilization, and aggregation are part of an antiviral response, in which tau serves as a host defense protein in the innate immune system of the brain,” the scientists wrote. “The combined antimicrobial activities of Aβ and phosphorylated tau resulting in Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, along with neuroinflammation, suggest that AD neuropathology may have evolved as an orchestrated innate immune host defense response to microbial infection in the brain.”

To get to that conclusion, Tanzi and his colleagues infected a human-derived neuron cell culture model with an affinity for phosphorylated tau with HSV1. They found that HSV1 infection caused hyperphosphorylation in tau, which in turn formed the characteristic protein aggregates observed in Alzheimer’s disease. Hyperphosphorylated tau then binds to the viral capsid, trapping and preventing it from attacking the neurons, ultimately neutralizing the infection.

“Our findings reveal an important novel role for tau as an antiviral protein against HSV1 and probably other viruses,” said William Eimer, PhD, lead author on the paper and an instructor in Mass Gen’s department of neurology. The findings suggest that “tangles may have originally formed in response to both amyloid and viral infection to prevent the spread of the virus from neuron to neuron in the brain.”