Chronic gastrointestinal pain conditions, including Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), are well known to impact women more often than men. While some work has connected gastrointestinal pain with estrogen, little has been done to clarify the mechanism behind this physiological phenomenon.

“Instead of just saying young women suffer from IBS, we wanted rigorous science explaining why,” said co-senior author Holly Ingraham, PhD, professor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Just how they have answered this question is described in their study entitled, “A cellular basis for heightened gut sensitivity in females,” is published in Science.

The team used a combination of tissue and whole animal experiments to determine the role that estrogen plays in gastrointestinal pain response. In the first set of experiments, the team used ex vivo mucosal preparations from mice comparing the afferent nerve fiber activity in culture. They tested mechanical and light stimulation effects on tissue samples from males, ovariectomized (OVX) females, and intact females. Male and OVX females both had significantly lower responses to stimuli compared with intact females.

In vivo experiments tested for visceral motor responses to colorectal distension to mimic pain assessment in patients with IBS. The responses in OVX females were again significantly lower than intact females. However, when treated with estradiol benzoate, OVX females had increased response, more akin to intact females.

“We knew the gut has a sophisticated pain-sensing system, but this study reveals how hormones can dial that sensitivity up by tapping into this system through an interesting and potent cellular connection,” said co-senior author and 2021 Nobel laureate David Julius, PhD, at UCSF.

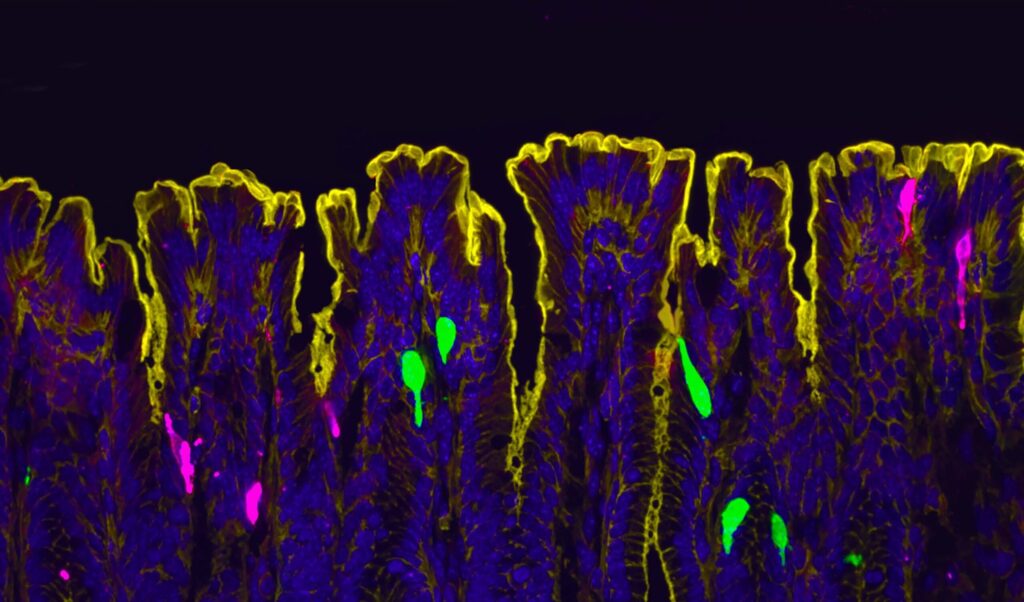

While the researchers expected to find estrogen receptors (ERα) in enterochromaffin (EC) cells—cells known to signal pain from the gut to spinal cord—they found that in fact, there were no ERα in the EC cells. Instead, they found that “Esr1 expression overlaps with 100% of Pyy-(and Cck)-expressing cells, especially in the distal colon.” They note that this lack of estrogen expression is consistent with gene expression data for EC cells and it led them to look at alternative sources of the estrogen response.

“PYY had never been directly described as a pain signal in the past,” said co-first author Eric Figueroa, PhD, a postdoc in Julius’ lab. “Establishing this new role for PYY in gut pain reframes our thinking about this hormone and its local effects in the colon.”

“At the time I started this project, we didn’t know where and how estrogen signaling is set up in the female intestine,” said co-first author Archana Venkataraman, PhD, a postdoc in Ingraham’s lab. “So, our initial step was to visualize the estrogen receptor along the length of the female gut.”

“Given the restricted expression of Esr1 in L cells, we asked whether estrogen promotes visceral pain by increasing L cell secretion of PYY,” the authors wrote. Further testing showed that PYY levels increase sensitivity in males and OVX females, but not in intact females, suggesting that PYY, specifically PYY1-36 is connected to gut sensitivity.

Additionally, estrogen increases expression of a short-chain fatty acid receptor, Olfr78, which in turn increases the sensitivity of L cells to bacterial metabolites. With more Olfr78 receptors, L cells become hypersensitive to these fatty acids and are more easily triggered to become active, releasing more PYY.

“It means that estrogen is really leading to this double hit,” said Venkataraman. “First it’s increasing the baseline sensitivity of the gut by increasing PYY, and then it’s also making L-cells more sensitive to these metabolites that are floating around in the colon.”

This study clarifies a novel mechanism by which L and EC cells interact, leading to hypersensitivity in the presence of increased estrogen levels.

“Identifying this protective signaling mechanism brings us closer to understanding how hormones and diet, when coupled with stress and inflammatory events, could become maladaptive, leading to chronic visceral pain,” concluded the authors.

“We’ve answered that question, and in the process identified new potential drug targets,” Ingraham said. Next steps for the research include searching for drugs that may be effective in reducing pain and inflammation and asking questions about the impacts of other hormone levels on gut sensitivity. They further question how hormone fluctuations during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and lactation may impact the gastrointestinal tract.