Researchers at the University of Exeter have discovered a potential new target against infections from Candida auris, a fungus responsible for deadly infections in at-risk populations. Thanks to the development of a new animal model to study host-pathogen interactions, the team found that C. auris upregulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism during infection.

“Since it emerged, Candida auris has wreaked havoc where it takes hold in hospital intensive care units. It can be deadly for vulnerable patients, and health trusts have spent millions on the difficult job of eradication,” said Hugh Gifford, MD, PhD, NIHR clinical lecturer at CMM and resident physician at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital. “We think our research may have revealed an Achilles heel in this lethal pathogen during active infection, and we urgently need more research to explore whether we can find drugs that target and exploit this weakness.”

Although Candida auris is known to live on human skin without causing harm, patients on ventilators or who are immunocompromised are at high risk of infection. Once an infection is established, the mortality rate is 45% and the fungus is often resistant to azole antifungals. With numbers of pan-drug resistant Candida auris infections on the rise, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies it as a critical priority fungal pathogen.

Despite the threat C. auris poses, there is limited knowledge about which genes are involved in the infection process due to major limitations of currently available animal models. On the one hand, mouse models cannot replicate the deadly effects of C. auris infections in humans. On the other hand, simpler organisms like flies and worms cannot model key elements of mammalian immune systems.

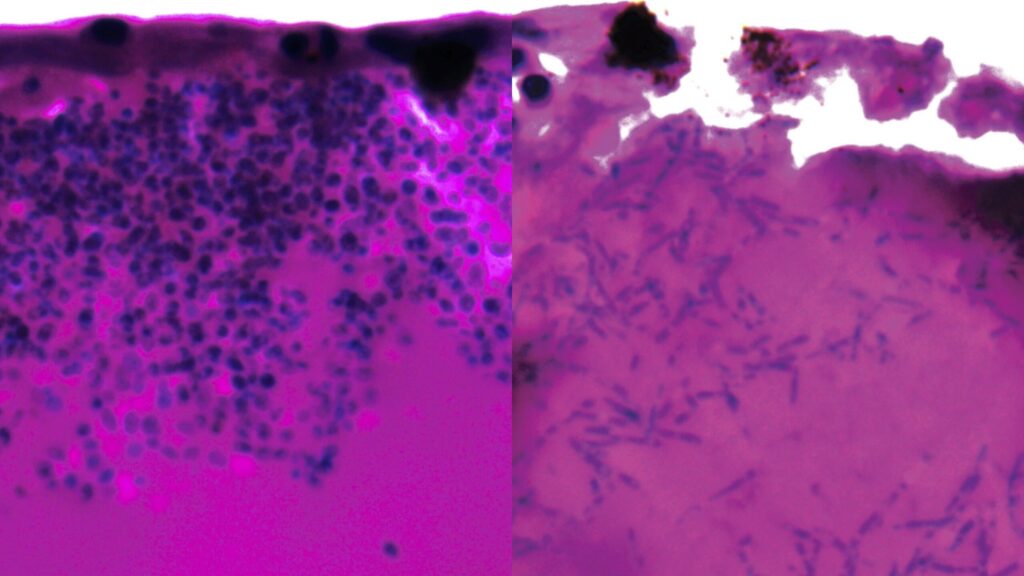

While some fish species can mount adaptive immune responses to fungal infections similar to those seen in humans, the zebrafish commonly used in research cannot stand temperatures above 30°C. Since fungal gene expression varies greatly depending on temperature, studying infection at body temperature is essential. This led Farrer and colleagues to model C. auris infections using Aphanius dispar, also known as Arabian killifish, a species known to stand temperatures of up to 40°C.

In a study published in Communications Biology, the researchers compared the in vivo and in vitro expression profiles of all five major clades of Candida auris. This allowed them to identify a gene expression signature shared across all clades that was consistently enriched for a series of siderophore transporter genes, including 12 xenosiderophore transporter candidate (XTC) genes and five haem transport-related (HTR) genes.

“Until now, we’ve had no idea what genes are active during infection of a living host,” said Rhys Farrer, PhD, senior lecturer in bioinformatics at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology (CMM). “The fact that we found genes are activated to scavenge iron gives clues to where Candida auris may originate, such as an iron-poor environment in the sea. It also gives us a potential target for new and already existing drugs.”

In other Candida species, including strains of C. albicans, iron uptake had been reported to play a central role in the pathogen’s survival during infection. These findings suggest that drugs targeting iron metabolism could offer a much-needed alternative to existing antifungal drugs. However, further work will be needed to confirm the role of these genes in key infection processes over time and investigate whether the same genes are involved in infections of human hosts.

“While there are a number of research steps to go through yet, our finding could be an exciting prospect for future treatment,” said Gifford. “We have drugs that target iron scavenging activities. We now need to explore whether they could be repurposed to stop Candida auris from killing humans and closing down hospital intensive care units.”