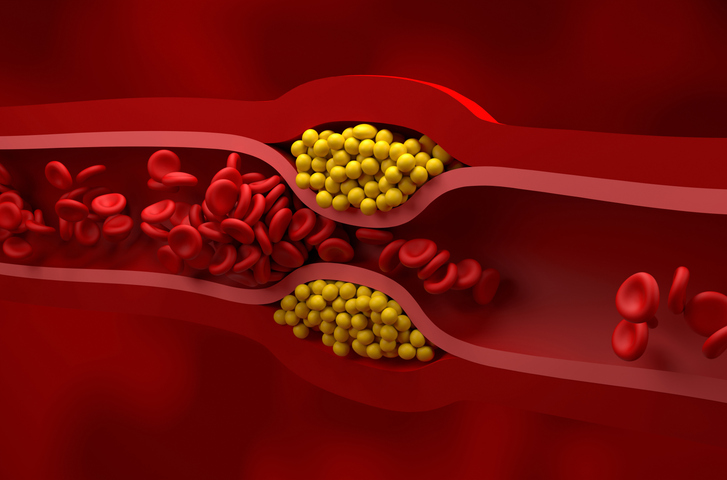

Aortic stenosis is one of the most common and deadly forms of heart valve disease, affecting millions worldwide. The condition develops gradually as the aortic valve narrows, eventually limiting blood flow from the heart. Yet despite its prevalence, medicine still lacks drugs that can prevent or slow its progression. Once the disease becomes severe, patients are left with only one option: valve replacement through surgery or catheter-based procedures.

A new study from researchers at UC San Francisco and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard suggests that this reactive approach may not be inevitable. By combining artificial intelligence–based imaging analysis with large-scale human genetics, the team has uncovered early genetic signals that shape aortic valve function long before clinical disease develops. The findings, published in Nature Genetics, point toward a future in which aortic stenosis could be detected, and potentially intercepted, years earlier.

“Our findings suggest that risk for aortic stenosis is conferred at least in part through the same genetic mechanisms that drive normal variation in aortic valve function in the healthy population,” said senior author James Pirruccello, MD, a cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF.

From late-stage diagnosis to continuous risk

One of the biggest challenges in studying aortic stenosis is that severe disease is relatively rare at the population level. Traditional genetic studies rely on comparing patients with advanced disease to controls, which limits statistical power and obscures early biology.

To overcome this, the researchers shifted focus from diagnosis to physiology. Instead of asking who has aortic stenosis, they asked how well the aortic valve functions across the general population.

Using deep learning models trained on cardiac MRI, the team extracted three continuous measures of aortic valve function—peak velocity, mean gradient, and aortic valve area—from nearly 60,000 UK Biobank participants who did not have diagnosed valve disease. These AI-derived measurements capture subtle differences in valve performance that are invisible in routine clinical care.

Genome-wide association analyses of these traits identified 61 genetic loci linked to normal valve function. The researchers then compared these results with a meta-analysis of more than 40,000 aortic stenosis cases and 1.5 million controls from multiple biobanks, uncovering 91 disease-associated loci.

When the datasets were analyzed together, the overlap became striking. A combined multi-trait analysis identified 166 genetic loci associated with aortic valve function or aortic stenosis, demonstrating that the boundary between “normal” valve variation and disease is genetically continuous.

Strong genetic overlap with disease

The study showed substantial genetic correlation between valve function in healthy individuals and clinical aortic stenosis. Gradient-based valve measures had a correlation of 0.64 with disease risk, while aortic valve area showed a correlation of 0.50.

In practical terms, this means that many of the same genetic variants that slightly alter valve function in healthy people also increase the likelihood of developing clinically significant stenosis later in life.

“Using deep learning to measure normal variation in aortic valve function helped us to identify 134 loci associated with aortic stenosis risk,” said Shinwan Kany, MD, a visiting scientist at the Broad Institute. “We observed strong associations between aortic stenosis risk and coronary artery disease, lipoprotein biology, and phosphate handling.”

These links reinforce the idea that aortic stenosis is not just a mechanical problem of aging valves, but a biologically regulated process influenced by metabolism, vascular disease, and mineral balance.

Implications for precision cardiology

Today, aortic stenosis is typically diagnosed only after symptoms appear or when imaging reveals advanced narrowing. By that point, irreversible valve damage has already occurred.

The new findings suggest a different model: identifying individuals genetically predisposed to valve narrowing based on subtle functional changes decades earlier. In a precision medicine framework, AI-derived imaging metrics combined with genetic risk scores could enable earlier monitoring, refined risk stratification, and targeted prevention strategies.

The authors emphasize that clinical validation is still needed. While the study highlights associations with cholesterol and phosphate pathways, it does not yet justify interventions to modify these factors specifically to prevent aortic stenosis.

Still, the work provides a roadmap for how cardiovascular diseases that currently lack medical therapies might be reclassified—from late-stage surgical conditions to lifelong, measurable biological processes.

“These findings demonstrate the power of jointly analyzing cardiovascular structure and function and their downstream disease outcomes,” Pirruccello concluded in a press statement.