Before a newly synthesized protein can undergo folding, it must be processed and transported to the correct location within the cell after emerging from the ribosome. N-terminal acetylation (Nt-acetylation) is a ubiquitous irreversible modification that affects a variety of protein properties and functions including folding, aggregation propensity, half-life, localization, and assembly. While modifications on histones influence chromatin function, how they occur co-translationally on these abundant and small proteins is not understood.

In a new study published in Science Advances titled, “Mechanism of cotranslational modification of histones H2A and H4 by MetAP1 and NatD,” researchers from ETH Zürich have uncovered how histones H4 and H2A undergo the correct chemical modifications during synthesis. The findings offer new avenues for diseases of histone dysregulation, such as cancer.

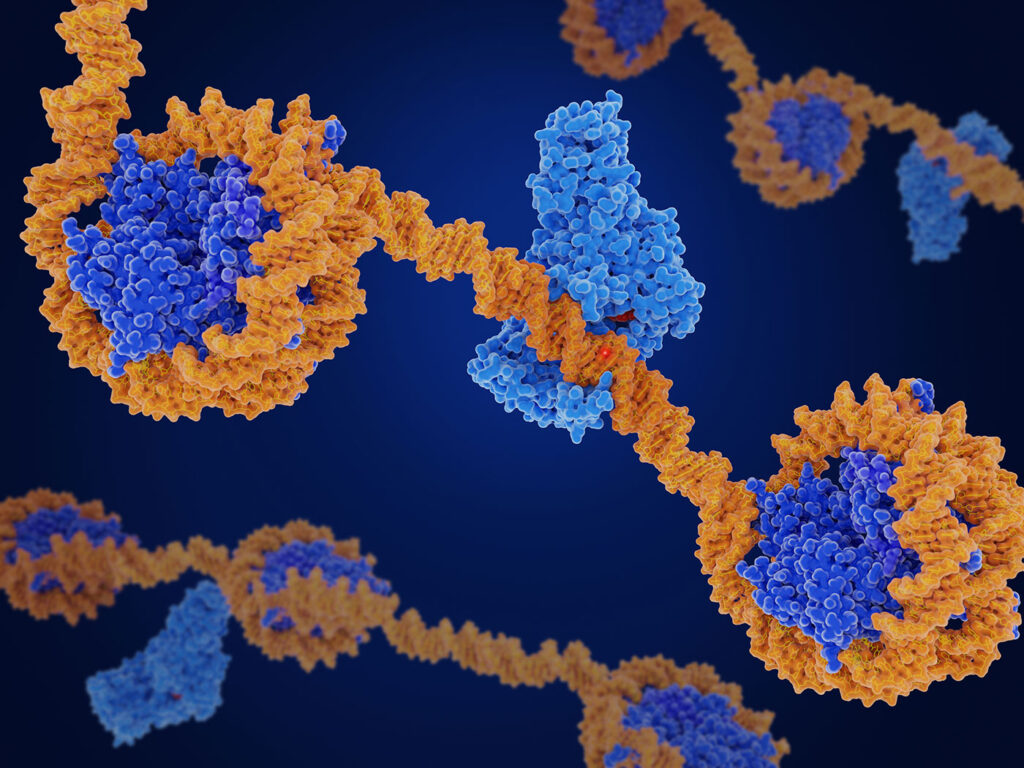

In eukaryotes, the heterodimeric nascent polypeptide-associated complex (NAC), an abundant ribosome-bound regulator of protein biogenesis, recruits and activates NatA to assist in the Nt-acetylation of approximately 40% of the mammalian proteome. NAC consists of two proteins that form a central ball-shaped core with four highly flexible extensions. One arm anchors NAC to the ribosome. The other three can bind a wide range of enzymes and other molecular factors involved in protein production.

Nearly all newly synthesized H2A and H4 are acetylated by N-terminal acetyltransferase D (NatD) following removal of the initiator methionine by methionine aminopeptidases (MetAPs).

The researchers show that NAC brings MetAP1 and NatD to the ribosome to remove the first amino acid from the histone protein and modify the newly exposed end with an acetyl chemical group. As histones are assembled very rapidly, these two processing steps must occur in the correct sequence.

“For histones, the time window for modifications is incredibly tight because their protein chains are very short,” explains Denis Yudin, graduate student at ETH Zürich and first author of the study. “NAC ensures that the right enzyme is at the right place at exactly the right time.”

Detailed structural information describing how NatD binds to one of NAC’s flexible arms could open new therapeutic strategies, such as drugs that block NatD’s interaction surface or prevent its recruitment to translating ribosomes. Additionally, NatD is frequently overproduced in certain types of cancer, altering gene regulation and promoting tumor growth. NAC’s control over the access of the enzyme NatD to the ribosome could provide new insights into tumor biology.

“The new findings change our view of protein synthesis,” said Nenad Ban, PhD, professor of structural molecular biology at ETH Zürich and corresponding author of the study. “They show how coordinated and dynamic the processes at the ribosome are, and how a small complex at the tunnel exit sets the pace for a large fraction of protein production in our cells.”

Ban describes NAC as a molecular gatekeeper rather than a passive scaffold. “By selectively opening or closing access to the ribosome depending on the type of protein that is being synthesized NAC acts like a remarkably precise sorter that nonetheless fully obeys the principles of thermodynamics,” explained Ban.