Longevity-linked enzyme shown to regulate brain metabolism, opening drug and biomarker opportunities for aging-related neurological disease.

A newly identified role for a longevity-linked brain enzyme could change how scientists – and investors – talk about neurodegenerative disease. Not at the symptom level. At the metabolic wiring level.

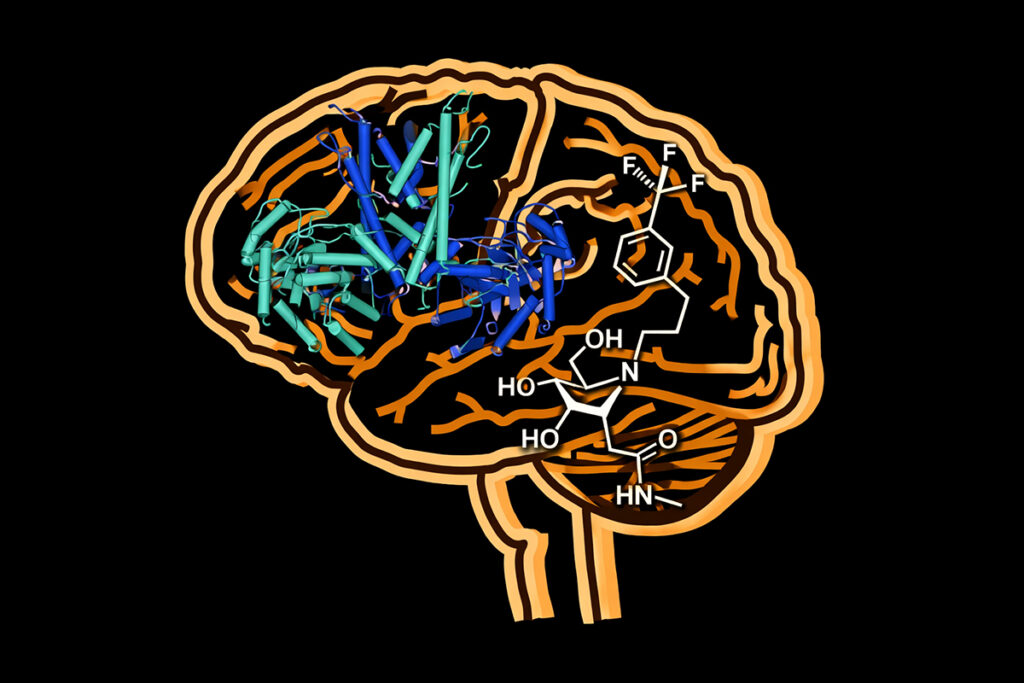

In a Nature Communications study, Israeli and European researchers report that sirtuin 6 (SIRT6), an enzyme long associated with aging and lifespan regulation, acts as a kind of biochemical traffic controller in the brain [1]. Not a passive timestamp of getting older. An active switch. One that decides what happens to tryptophan – an essential amino acid with a surprisingly split personality.

On one side sits the familiar story: tryptophan as the feedstock for serotonin and melatonin, the mood-and-sleep duo that dominates public discourse (and supplement marketing). On the other sits the less glamorous but arguably more consequential route: the kynurenine pathway, a metabolic pipeline that helps generate cellular energy but can also produce neuroactive metabolites with a darker edge.

Balance matters. A lot.

Aging, neurodegenerative disease, and psychiatric conditions have long been linked to disruptions in this tryptophan balance. Insomnia. Depression. Cognitive fog. Impaired learning. The pattern shows up over and over – but until now, the molecular lever behind the shift has been hard to pin down.

“This imbalance has been documented repeatedly, but the mechanism behind it remained a mystery,” said Professor Debra Toiber of Ben-Gurion University’s Department of Life Sciences, who led the research.

Using human cell lines alongside mouse and fruit fly models, Toiber’s team identified SIRT6 as the central regulator of tryptophan metabolism in the brain. When SIRT6 activity is intact, tryptophan is partitioned with something close to metabolic discipline: enough flows toward serotonin and melatonin to support mood, sleep, and neuronal stability, while the rest feeds energy production through kynurenine [1].

Then aging enters the frame. SIRT6 activity declines naturally over time – and the distribution system starts to fail.

As SIRT6 levels drop, the study found, tryptophan doesn’t simply drift off course. It gets rerouted. Actively. More of it is pushed toward the kynurenine pathway. That pathway keeps the lights on – but it also generates byproducts the researchers flagged as toxic to nerve cells, like a power plant that also leaks waste into the water supply. Meanwhile, serotonin and melatonin production falls, stripping the brain of compounds that help protect neurons and keep circadian rhythms from fracturing.

“This is not just a gradual decline,” Toiber said, “It is an active metabolic rerouting that damages the nervous system [2].”

The most interesting part, though, isn’t the mechanism. It’s what happens when you interfere with it.

Crucially, the researchers showed the damage isn’t inevitable – and, at least in model organisms, it’s not irreversible.

In fruit fly models lacking SIRT6, the team inhibited a second enzyme, TDO2, which plays a key role in directing tryptophan into the kynurenine pathway. Blocking TDO2 significantly reduced neuromotor decline and limited pathological changes in brain tissue. In other words: cut the rerouting signal, and the nervous system stops taking as much collateral damage [1].

Toiber explained that their findings established the enzyme SIRT6 as a critical target for pharmacological intervention against brain degeneration.

“These findings change the way we understand the relationship between aging and brain function. It is not simply wear and tear, but a specific metabolic malfunction that can be corrected,” she noted [2].

That framing matters for longevity science because it shifts the emphasis away from inevitability and toward control – the idea that “aging” isn’t just accumulated scarring, but a set of programmable failure modes in metabolism.

For investors, the map changes too. Rather than chasing downstream effects – amyloid, tau, synaptic collapse, movement dysfunction – this work suggests an upstream strategy: restore metabolic balance before the neural circuitry starts shorting out. Boost SIRT6 activity. Or selectively inhibit TDO2. Either approach could, in theory, reduce neurotoxic metabolite buildup while bringing serotonin and melatonin production back online.

The study also nudges open a practical door: development timelines. TDO2 has already been investigated in other therapeutic arenas, including cancer and immunology. That means experimental inhibitors exist, and partial safety packages may already be on shelves somewhere, waiting to be re-labeled for neurological indications – or refined into more brain-specific candidates.

Treatment isn’t the only angle. Diagnostics show up in the margins here too.

Shifts in tryptophan metabolites – or a measurable drop in SIRT6 activity – could evolve into early biomarkers, detectable via blood or cerebrospinal fluid tests. These signals could help identify individuals trending toward cognitive decline, sleep disruption, or mood disorders before symptoms harden into disability. They could also offer a more responsive way to track disease progression and treatment impact, especially in trials where traditional endpoints move slowly and noisily.

The international collaboration included Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, KU Leuven’s VIB Center for Cancer Biology in Belgium, the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology in Russia, and the University of South Bohemia in the Czech Republic.

As longevity research increasingly collides with neurology, the discovery positions metabolic regulation – not just protein aggregation or neuron loss – as a frontier worth watching. And possibly, investing in.

[1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67021-y

[2] https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/brain-enzyme-discovery-may-open-new-path-to-treat-neurodegenerative-disease/article70427104.ece