Northwestern researchers unveil the most detailed 3D genome maps, revealing how DNA folding regulates genes and disease risk.

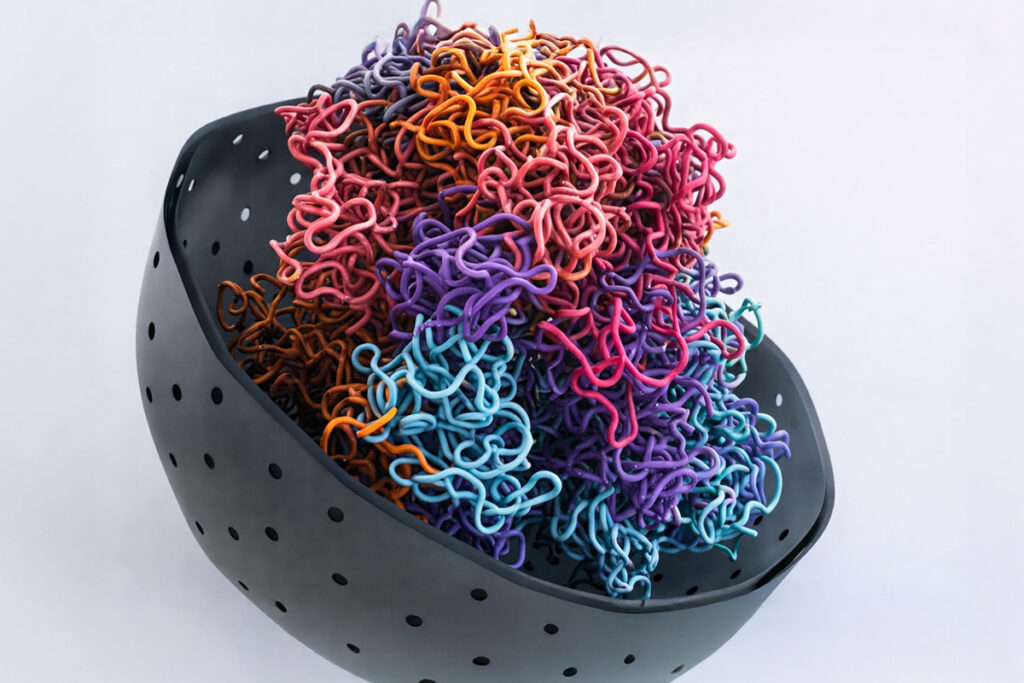

For decades, we’ve talked about the human genome as if it’s a tidy, one-dimensional string of letters – A, T, C, G – like a biological barcode that explains everything. Convenient. Also misleading. Because inside the nucleus, DNA doesn’t sit politely in a straight line. It folds, loops, coils, and tucks itself into an ever-shifting origami of chromatin that decides, in very real terms, which genes get to speak and which are gagged.

And that’s the point of new work from Northwestern University and the 4D Nucleome Project: the genome’s geometry is as important as its sequence. Maybe more.

“Understanding how the genome folds and reorganizes in three dimensions is essential to understanding how cells function,” said Feng Yue, co-corresponding author and Duane and Susan Burnham Professor of Molecular Medicine. “These maps give us an unprecedented view of how genome structure helps regulate gene activity in space and time.”

Published in Nature, the study treats DNA less like a static instruction manual and more like a living control system – one that actively shapes cellular behavior. In that model, the 3D “wiring” of the genome influences everything from stem cell fate decisions to what happens when gene regulation goes sideways and disease emerges [1].

To capture that architecture with unusual granularity, the team profiled human embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts, stitching together multiple genomic technologies into a high-definition 3D portrait. The headline results land with a thud:

- More than 140,000 chromatin loops per cell type, pinning down the anchoring elements that bring distant regulatory regions into physical contact with genes.

- A finely resolved taxonomy of chromosomal domains, mapped with their precise nuclear neighborhoods.

- Single-cell, high-resolution 3D genome models, charting where individual genes sit relative to their regulatory elements and chromatin context.

Here’s the part that makes the data feel almost unsettling: no two cells fold their genomes in exactly the same way. Even within the same cell type, the chromatin landscape varies – and those variations are not decorative. They influence core processes like transcription (the cell reading its genetic script) and DNA replication.

“Rather than being static, the genome is dynamic. Its structure changes as cells function, divide, and respond to signals, and this folding directly affects which genes are turned on or off,” Yue explained.

Mapping something this complex is like trying to reconstruct a city from satellite images, street-level photos, and traffic patterns – each view catches different truths, each misses something essential. So the researchers didn’t just generate maps; they benchmarked the mapping tools themselves, stress-testing how well different assays detect loops, domain boundaries, and subtle shifts in nuclear positioning. That might sound like a methodological footnote. It isn’t. For structural genomics – and for any biotech hoping to build diagnostics or therapeutics from genome architecture – it’s a practical playbook.

Better assay selection means better experiments. Less noise. Faster iteration.

Then the team went a step further: they developed computational tools capable of predicting how DNA folds from sequence alone. No experimental scaffolding required. That opens the door to something that gets investors’ attention quickly – a way to forecast how genetic variants might warp 3D genome structure, and what that distortion could do to gene expression, without having to build a full experimental pipeline every time.

“Most variants associated with human diseases are in non-coding regions. Understanding how these variants influence gene expression is critical. The 3D genome provides a framework for predicting which genes are likely affected by pathogenic changes,” Yue said.

Why this matters for medicine – and the longevity-adjacent biotech thesis

Genome misfolding isn’t just academic. Altered 3D architecture has been observed in cancers including leukemia and brain tumors, where regulatory loops and domain boundaries can be rewired in ways that switch oncogenic programs on and keep tumor suppressors quiet. If you can identify those structural failures – and, crucially, find ways to nudge them back – you’re talking about a different class of intervention.

Not symptom management. Circuit repair.

That’s where epigenetic drugs and chromatin-modulating strategies start to look less like blunt tools and more like precision instruments: compounds that could, in theory, reshape genomic architecture and restore healthier patterns of gene regulation.

For biotech firms and investors, the implications are broad:

- Structural genomics-based diagnostics that detect disease risk not just from sequence variants, but from how the genome physically arranges itself.

- Precision medicine pipelines that connect non-coding variants to downstream gene targets through 3D contacts, improving variant interpretation.

- Drug discovery opportunities focused on chromatin architecture as a therapeutic lever – especially in diseases where regulation fails long before cells look “sick.”

Beyond oncology, the same logic extends into developmental disorders and inherited diseases, where subtle disruptions in chromatin domains can produce outsized effects. And because many longevity-relevant phenotypes – cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, dysregulated repair – sit downstream of gene expression programs, 3D genome mapping starts to look like infrastructure, not ornamentation.

The bigger shift here is conceptual. The genome’s function can’t be fully inferred by reading the letters alone. Its shape is part of the code. Loops, boundaries, compartments – this is the operating system that decides what runs, when, and how loudly.

Looking ahead, Yue’s group wants to go from mapping and prediction to intervention – to test whether these structures can be deliberately tuned, including with epigenetic inhibitors.

“Our next aim is to explore how these structures can be targeted and modulated using drugs such as epigenetic inhibitors,” he said.

As 3D genome maps become sharper – and as predictive models get better at simulating architecture from sequence – the translational runway lengthens. This is one of those moments where fundamental biology and biotech opportunity start to overlap in a very investable way: a clearer path from mechanism to target, from variant to function, from structure to therapy.

The genome isn’t just written. It’s folded.