Researchers at Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Cambridge Centre and the University of Cambridge have shown that an existing medication for managing hot flushes that mimics the hormone progesterone can slow tumor growth in estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive) breast cancer when combined with standard anti-estrogen therapy. The effect was seen in post-menopausal women with early-stage ER-positive, HER2-negative disease, which accounts for around three-quarters of all breast cancers. The findings, published in Nature Cancer, provide added evidence that low doses of the drug megestrol acetate could alter how ER-positive breast cancer is treated in the future.

“On the whole, anti-estrogens are very good treatments compared to some chemotherapies. They’re gentler and are well tolerated, so patients often take them for many years. But some patients experience side effects that affect their quality of life. If you’re taking something long term, even seemingly relatively minor side effects can have a big impact,” said senior author and trial leader Richard Baird, MD, PhD, of University of Cambridge.

Megestrol acetate is a synthetic progestogen that mimics the hormone progesterone which has, at higher doses, already received regulatory approval for the treatment of metastatic ER-positive breast cancer. However, long-term use can be associated with side effects such as weight gain and hypertension. Lower daily doses in the 20 mg to 40 mg range have already shown in earlier trials to relieve hot flushes in women receiving anti-estrogen therapy, a side effect that often leads patients to stop treatment early.

Data from the new combination treatment strategy are from the PIONEER clinical trial, a Cambridge-led, randomized Phase IIb “window-of-opportunity” study designed to test whether targeting the progesterone receptor alongside estrogen deprivation could enhance anti-cancer effects. The trial has enrolled 198 post-menopausal women with operable ER-positive breast cancer at 10 U.K. hospitals. Participants were randomized to receive the aromatase inhibitor letrozole alone, letrozole plus 40 mg of megestrol acetate daily, or letrozole plus 160 mg of megestrol daily. Treatment was given for two weeks prior to surgery, allowing researchers to compare tumor samples taken before treatment and at surgery.

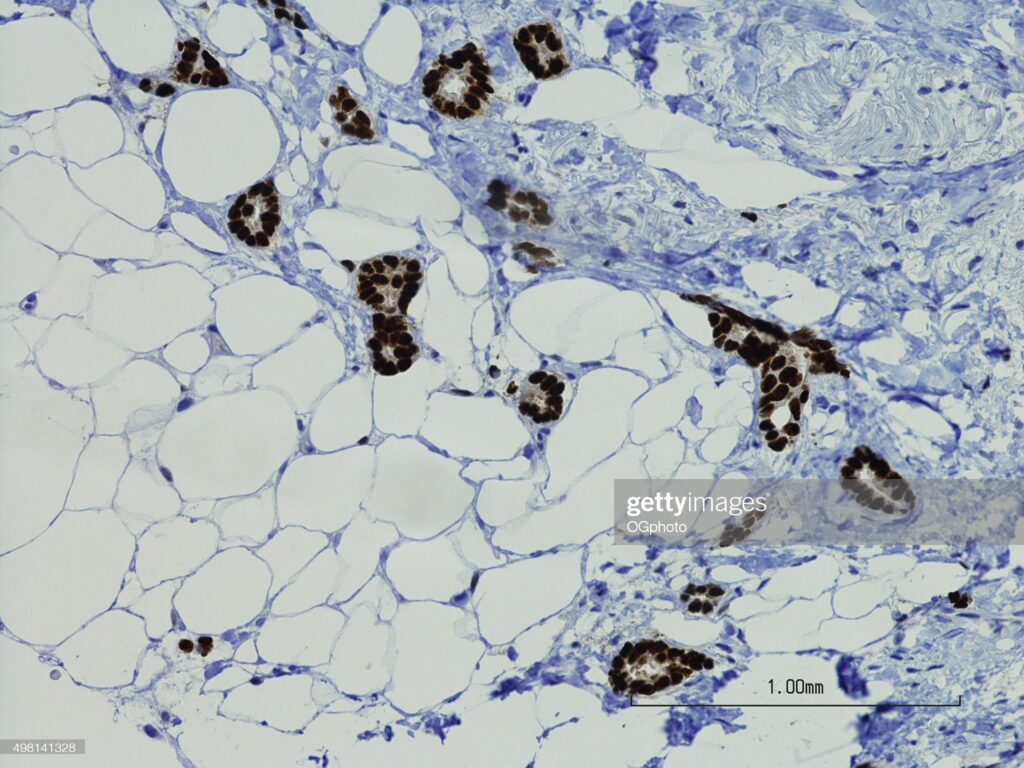

The data showed that the trial met its primary endpoint, with a greater reduction in tumor proliferation observed when megestrol was added to letrozole. Tumor proliferation was measured using Ki67 immunohistochemistry, a marker commonly used in short presurgical studies of endocrine therapy. Comparable reductions in proliferation were observed with both the lower and higher doses of megestrol.

“In the two-week window that we looked at, adding a progestin made the anti-estrogen treatment more effective at slowing tumor growth,” said joint first author Rebecca Burrell, PhD, a research associate at CRUK. “What was particularly pleasing to see was that even the lower dose had the desired effect.”

Previous research had demonstrated the potential of this therapeutic approach which prompted the clinical trial. Studies in cell cultures and mouse models had shown that progesterone can interact with the estrogen receptor and alter its activity, leading to slower tumor growth. “Treating mouse xenograft models with both progesterone and anti-estrogen therapy led to greater inhibition of tumor growth than either treatment alone,” the researchers wrote, which suggested that progesterone receptor activation could complement standard anti-estrogen therapy.

If confirmed in additional clinical studies, there are a couple of implications for clinical care for this approach. First, low-dose megestrol could help patients tolerate long-term anti-estrogen therapy by reducing hot flushes, which would likely increasing treatment adherence. Second, the drug itself appears to enhance tumor growth suppression when combined with an aromatase inhibitor. Because megestrol is off-patent, it could become a cost-effective option, particularly in care settings where newer targeted therapies are less accessible.

The researchers now plan to launch a new phase of the research in a larger cohort of patients treated to for a longer duration to determine if the drug would have the same treatment benefits and reduced side-effects.