As winter swoops over the world, wrapping the days in mist and hardening the ground beneath a layer of frost, people retreat indoors to snuggle into cozy blankets. With heaters humming in the background, they indulge in steaming hot chocolate to keep themselves warm. However, not all animals on the planet have this luxury. They have come up with other strategies to survive frigid temperatures.

Some frogs adopt an unusual approach: Wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) and Cope’s gray tree frogs (Dryophytes chrysoscelis) bury themselves under leaves on the forest floor, which offers some protection from the cold. However, as temperatures drop below zero degree Celsius, the amphibians freeze up to 65 percent of the water in their bodies, become metabolically inactive, and show no signs of heartbeat, breathing, or nerve conduction.

Wood frogs freeze themselves solid during winter.

Rasha Al-Attar

“For all intents and purposes, this animal is clinically dead,” said Shannon Tessier, whose research at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) involves leveraging lessons from nature for biomedical applications.

Upon freezing, the frogs become solid. “If you hold a frozen frog, it’s literally like a rock,” said Rasha Al-Attar, a biologist who works in Tessier’s lab at MGH. As winter melts into spring and temperatures rise, the frozen amphibians gradually thaw “and start going about [their] day as though nothing had happened,” added Al-Attar.

Inspired by their natural antifreeze properties, scientists have been exploring how to apply the frogs’ survival tactics to better preserve human cells, tissues, and organs.1,2 This is particularly important to boost transplant outcomes as well as to provide more time for distributing transplantable tissues and organs across geographies. In fact, testing some processes drawn from freeze-tolerant frogs prolonged the cryopreservation of some animal organs, offering promising evidence supporting nature-inspired organ cryopreservation strategies.

Current Cryopreservation Challenges and Opportunities

Millions of people across the world suffer from end-stage organ failure. In the United States, about 13 people die every day waiting for a lifesaving organ transplant surgery; more than 100,000 are on the waitlist—which grows by one person every eight minutes—to receive an organ.

One of the major challenges that impedes more transplantation surgeries is the shortage of available organs, which is compounded by the fact that they cannot be stored for a long duration.3 The most commonly used method currently to store harvested organs is static cold storage. “You put the organ in a bag of ice and run to the recipient. You have in the order of hours,” explained Korkut Uygun, a chemical and systems engineer at MGH.

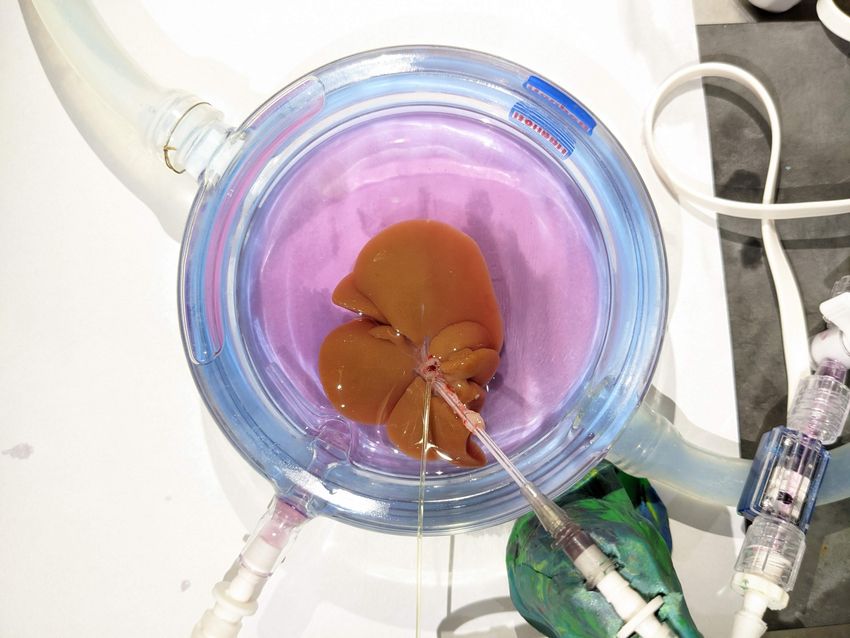

Uygun, Toner, and their teams work with rodent livers to study the effect of nature-inspired cryopreservation strategies. Captured here is a rat liver prior to freezing at -15°C.

Katherine A. Flock, Casie Pendexter/Mass General Brigham

“Organs live [in human bodies] for 70, 80, 90 years. You take it out, [and] in six hours, [it] says ‘I’m out, I’m gone’,” said Mehmet Toner, a biomedical engineer at MGH. This means that all organ transplantation surgeries are done on an emergency basis, as and when organs become available, either donated by living people or harvested from individuals deceased due to brain or circulatory death. “There’s essentially no logistics, no supply chain for organs,” said Uygun.

Toner and Uygun hope to solve this problem. They study ways to extend the duration over which harvested organs can be stored for transplanting into patients whenever required, similar to “the way you can buy something on Amazon that drops in front of your door,” said Uygun.

To this end, the researchers draw on work conducted by Tessier and others in the field investigating animals that have devised ingenious methods to suspend their biological processes in time, such as freeze-tolerant frogs. “Scientists always look for answers in nature,” said Toner. “And for billions of years, nature figured this out.” For instance, the fact that frogs can bounce back from their frozen state without any damage can provide important insights into reducing the effects of ischemia/reperfusion injury that inevitably happens after an organ is transplanted: Blood suddenly gushes into the organ—which lacked blood flow during preservation and transport—triggering an immune cascade that can cause graft dysfunction or failure.4

Decoding How Frogs Tolerate Repeated Freeze-Thaw Cycles

To investigate how frogs survive repeated freeze-thaw rounds throughout the year, scientists collect these animals, put them on wet paper towels in plastic boxes, and freeze the set up. “As soon as ice forms on the wet paper towel, it propagates the wood frog skin, and then they freeze,” said Al-Attar. This slows down metabolic processes and freezes a majority of their body’s water in the extracellular space. “And then, whenever we want to thaw them, we just take them out, put them at four degrees, and then bring them to room temperature,” Al-Attar explained.

Biochemical and physiological analyses have offered some insight into how frogs deal with the frozen conditions. For instance, by measuring the concentration of different molecules in frozen Cope’s gray tree frogs, scientists discovered that the animals accumulate glycerol.5

“What the glycerol does really is [it] cryoprotects the cells from the physical insult of freezing and thawing,” said Carissa Krane, a biologist who studies freeze tolerance in Cope’s gray tree frogs at the University of Dayton. Microscopic observation of cells from cold- and warm-acclimated animals revealed some differences: The former burst open at a lower rate than the latter upon putting water in the suspension. “They really tolerate that osmotic pressure well,” said Krane. She explained that glycerol equilibrates across cell membranes to moderate osmotic pressure, which prevents water from gushing into the cells when the animals thaw in warmer temperatures.

To better understand how the frogs accumulate glycerol upon cold exposure, Krane and her team carried out RNA sequencing of the amphibians’ liver cells through different stages of freezing and thawing.6 They observed decreased expression of the gene encoding an enzyme that metabolizes glycerol, possibly promoting the cryoprotectant’s buildup.

“One of the reasons why this organism is very interesting to us is that this glycerol mechanism has been shown in other systems to work as a very good cryoprotectant,” said Krane. For instance, researchers use glycerol to store microorganisms below freezing temperatures and to cryopreserve animals’ sperm for assisted reproductive technologies, showing the promise of such frog-inspired strategies.7

In contrast to Cope’s gray tree frogs, wood frogs use glucose as their primary cryoprotectant. They accumulate glucose in their bodies by suspending the metabolic pathways that take up the molecule.

Additionally, wood frogs show several adaptations during late fall to prepare for freezing during the winter. They accumulate glycogen which serves as fuel, modify cell membranes which prevents the cells from collapsing, and increase antioxidants to fight oxidative damage.8 The animals also reduce their metabolism to utilize the stored energy only for processes absolutely crucial for survival.

While some of these mechanisms are well-established in frogs, “how do you achieve that in a human or other non-tolerant animal is not explicitly clear,” said Tessier. So, researchers rely on lessons from comparative biology but also apply principles of chemistry and engineering to impart non-tolerant cells the properties of freeze-tolerance. “We try to borrow these lessons from nature but not necessarily mimic it exactly.”

Frog-Inspired Cryopreservation Strategies Show Promise

Scientists perfuse a rat liver with cryoprotectants to prevent damage due to freezing.

Katherine A. Flock, Casie Pendexter/Mass General Brigham

Scientists have begun applying some early lessons from frogs to mammalian systems.

For instance, frogs preferentially form ice in their extracellular spaces and not within the cells. Drawing on this, Tessier, Toner, and their colleagues identified a bacterially derived product that helped them control ice nucleation in extracellular vasculature for cryopreserving cells.9,10

Inspired by wood frogs’ ability to build up glucose as a cryoprotectant, Toner and Uygun pursued investigations on similar lines. “[However], glucose in mammalian cells is toxic at the concentrations that we need to use,” said Toner. So, the researchers turned to a glucose analog that has a chemical modification that prevents mammalian cells from metabolizing it.11

Using this method, the researchers could improve the viability of rat liver cells after thawing them. The analog along with supercooling and reperfusion strategies also prolonged the cryopreservation of rat livers for up to four days.12 The researchers also successfully transplanted a porcine kidney cryopreserved for more than a week using some nature-inspired strategies.

By leveraging some nature-inspired strategies, Uygun and his team recently stored a pig kidney in freezing conditions for 10 days.

Jeffrey Andree, Casie Pendexter, McLean Taggart/Mass General Brigham

While the glucose analog exerts the cryoprotective effects of glucose without causing the toxicity, not all cryoprotectants may have such workarounds. So, Al-Attar is exploring synthetic biology-based approaches and transient gene editing to increase cells’ tolerance and reduce the toxicity of cryoprotective agents such as dimethyl sulfoxide, which is used to preserve mammalian cell lines.

But cryoprotectants are just one line of defense to protect the cells from the side effects of freezing. In addition to mobilizing such molecules, frogs also reduce their metabolism significantly when frozen. Based on this, Toner and his colleagues treated several mammalian cell lines with a drug to downregulate biosynthetic processes and observed improved post-thaw viability.13

The Future of Nature-Inspired Organ Cryopreservation Strategies

Even though individual strategies have offered some promise, Uygun noted that several events must come together to achieve freeze-tolerance. “There’s no magic molecule, [where] you add one thing and everything [gets] solved,” he noted. “It needs to be orchestrated because that’s really how nature does [it]. There’s some coordination, some choreography.”

Doctors recover porcine kidney after thawing it, just before transplanting it into a recipient pig.

Jeffrey Andree, Casie Pendexter, McLean Taggart/Mass General Brigham

Krane agreed that individual freeze-tolerant species have offered important insights into this process. “The challenge for us is to really put all of the pieces together…to put all of those data together from multiple different models.”

Despite the challenges and mammoth task ahead, Uygun noted that the environment is ideal for applying lessons from nature to improve transplant outcomes. Clinicians are largely accepting of such strategies to extend the lives of harvested organs, which is a promising sign for the field of transplantation medicine, he said.

“Five years from now the landscape of transplantation will be very different,” agreed Toner.

Tessier, Toner, and Uygun marveled at the idea that such nature-inspired strategies could one day enable transplantation surgeons to have a catalog of cryopreserved organs to choose from. “That would be the ultimate dream,” said Tessier.

- Al-Attar R, Storey KB. Lessons from nature: Leveraging the freeze-tolerant wood frog as a model to improve organ cryopreservation and biobanking. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2022;261:110747.

- Yokum EE, et al. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles in freeze-tolerant treefrogs: Novel interindividual variation of integrative biochemical, cellular, and organismal responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2023;324(2):R196-R206.

- Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Grand challenges in organ transplantation. Front Transplant. 2022;1:897679.

- Liu J, Man K. Mechanistic insight and clinical implications of ischemia/reperfusion injury post liver transplantation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15(6):1463-1474.

- Storey JM, Storey KB. Adaptations of metabolism for freeze tolerance in the gray tree frog, Hyla versicolor. Can J Zool. 1985;63(1): 49-54.

- do Amaral MCF, et al. Hepatic transcriptome of the freeze-tolerant Cope’s gray treefrog, Dryophytes chrysoscelis: Responses to cold acclimation and freezing. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):226.

- Ogata K, et al. Optimization of canine sperm cryopreservation by focusing on glycerol concentration and freezing rate. Vet Res Commun. 2025;49(2):86.

- Storey KB, Storey JM. Molecular physiology of freeze tolerance in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):623-665.

- Weng L, et al. Controlled ice nucleation using freeze-dried Pseudomonas syringae encapsulated in alginate beads. Cryobiology. 2017;75:1-6.

- Tessier SN, et al. Effect of ice nucleation and cryoprotectants during high subzero-preservation in endothelialized microchannels. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(8):3006-3015.

- Sugimachi K, et al. Nonmetabolizable glucose compounds impart cryotolerance to primary rat hepatocytes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(3):579-588.

- Berendsen TA, et al. Supercooling enables long-term transplantation survival following 4 days of liver preservation. Nat Med. 2014;20(7):790-793.

- Menze MA, et al. Metabolic preconditioning of cells with AICAR-riboside: Improved cryopreservation and cell-type specific impacts on energetics and proliferation. Cryobiology. 2010;61(1):79-88.