Researchers at the National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) have newly identified sets of genetic variations that increase susceptibility to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and influence survival once the disease develops. The findings, published in Nature Communications, show that mutations in two genes, FCN1 and PLAT, a part of the innate defense mechanism called the complement system, are associated with an increased risk of developing PDAC, while the expression of other complement system genes shapes immune cell infiltration and prognosis. Together, the results suggest that genetic profiling of complement system pathways could help identify individuals at higher risk of PDAC and guide earlier surveillance strategies, a critical step for a cancer that is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage.

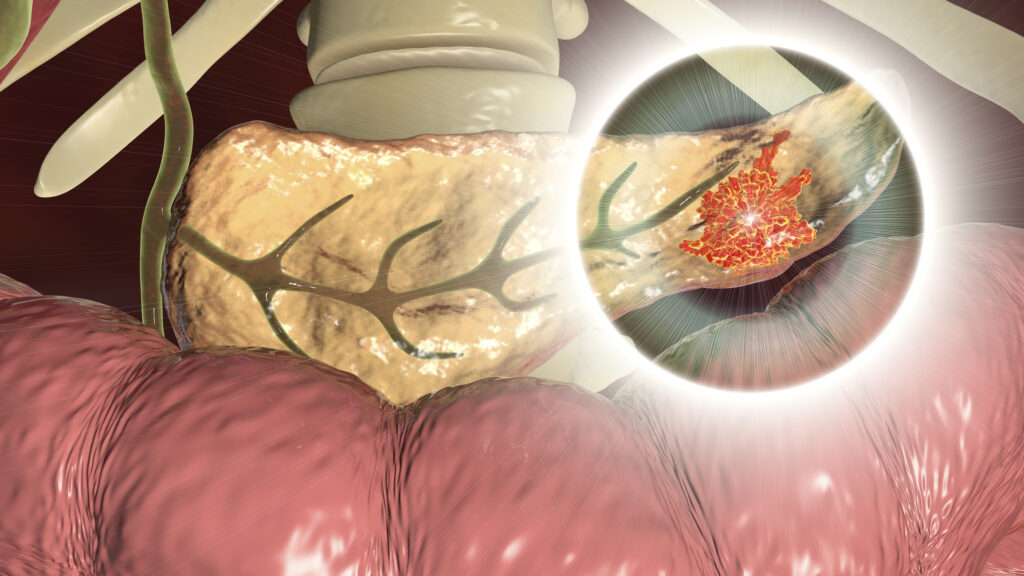

Pancreatic cancer is among the deadliest solid tumors. PDAC accounts for about 95% of cases, and patients have a five-year survival rate of 5% to 10%. Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal cancers, and its prognosis is unlikely to improve “unless multiple actions are taken,” the researcher noted, which could include the identification of high-risk populations who could undergo more regular screening designed to diagnose PDAC development early.

The new study builds on research that has linked immune-related genetic regions to PDAC. These studies have implicated the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) in pancreatic cancer risk, but most work focused on MHC class I and II regions. The complement system, which is encoded largely within the MHC class III region has received less scrutiny in PDAC research despite that fact that complement genes are prognostic indicators in other cancer types.

To address this gap, the CNIO-led team conducted a hypothesis-driven analysis of genetic variation across 111 complement system–related genes using data from the PanGenEu study, a European research project seeking to define risk factors for PDAC. Their analysis to identify SNPs associated with disease risk were then validated against data from the UK Biobank. The team found that genetic variation in FCN1 and PLAT showed a significant association with PDAC risk. These genes are involved in immune defense, tissue remodeling, and interactions with coagulation pathways, processes already known to be altered in pancreatic cancer.

The researchers then tested how these genetic signals might affect disease behavior using functional in silico analyses and large transcriptomic datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas and the International Cancer Genome Consortium. “Results from this study suggest that [complement system]-related genes play a role in PDAC genetic susceptibility and survival through specific immune cell infiltration,” the researchers wrote.

In addition to identifying variants that make people more susceptible to PDAC, the researchers also identified several complement-related genes linked to improved survival when highly expressed, such as IGHG3, IGKC, IGHM, A2M, F2R, F2RL2, CFI, and C4A. Tumors with higher expression of these genes showed greater infiltration of CD8+ T cells, B cells, and Th1 cells. Conversely, higher expression of genes such as FGA, FGG, SERPINE1, and F3 was associated with poorer survival, increased regulatory T cells, and reduced CD8+ infiltration.

These immune patterns are especially relevant in PDAC, which is considered a “cold” tumor that typically evades immune recognition and responds poorly to immunotherapy. “Understanding the relationship between the genes of the complement system and pancreatic cancer may also have implications for treatment,” the researchers wrote. This knowledge opens the possibility of new immunotherapies targeted at these genes.

These findings could eventually provide clinical benefits. First, FCN1 and PLAT could be developed as biomarkers for diagnostic approaches that could identify those at higher genetic risk who could benefit from regular monitoring before symptoms appear. Second, complement-related gene expression signatures could help stratify patients by prognosis and inform treatment strategies once PDAC is diagnosed.

Next in this line of inquiry is validating these findings in non-European populations, exploring rare genetic variants. “Future research should focus on unraveling the intricate mechanisms through which these complement-related genes contribute to PDAC development, as well as exploring their potential as therapeutic targets in PDAC tumors,” the researchers noted.