Pangenomics, the study of many different genomes from one species, can provide a more holistic picture of the natural variation and mutations that occur within a species than using one singular reference genome.

Although advances in NGS technologies have reduced the cost and increased the speed of sequencing, the data structures and analysis tools needed to study and graphically represent the relationships between millions of sequenced genomes remain a challenge. While graph-based data formats for pangenomes have become popular and widely adopted, they only represent the genetic variation in a collection of genomes, not their shared evolutionary and mutational histories. They also have large storage requirements that do not scale well.

Now, a new data structure and compression technique has been developed that enables the field of pangenomics to handle unprecedented scales of genetic information.

This work is published in Nature Genetics in the paper, “Compressive pangenomics using mutation-annotated networks.”

“The data structures used for pangenomics research are critical because they determine not only how efficiently genetic data is represented, but also what the data can represent,” said Sumit Walia, an electrical engineering PhD candidate in the lab of Yatish Turakhia, PhD at the Jacobs School of Engineering at the University of California, San Diego.

The research team pioneered a new data structure and file format, called Pangenome Mutation-Annotated Network (PanMAN), a “lossless pangenome representation that achieves compression ratios ranging from 3.5–1,391× in file sizes compared to existing variation-preserving formats, with performance generally improving on larger datasets.”

PanMAN not only provides unmatched compression for pangenomes but also significantly advances the representative power by encoding additional biologically relevant information, including phylogenies, mutations, and whole-genome alignments. Their compressive pangenomics approach can perform analysis on compressed pangenomic data, allowing researchers to handle vastly larger scales of genetic data than currently possible.

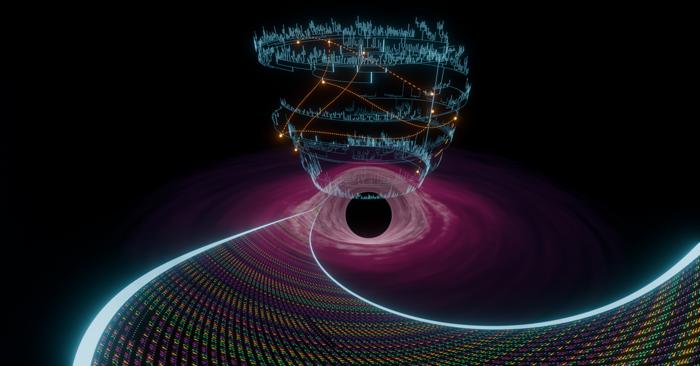

PanMANs are composed of mutation-annotated trees, called PanMATs, which store a single ancestral genome sequence at the root and annotate mutations, such as substitutions, insertions, and deletions, on the different branches. Multiple PanMATs are connected in the form of a network using edges to generate a PanMAN. These edges store complex mutations, such as recombination and horizontal gene transfer data, which result in sequences involving multiple parent sequences and violate the vertical inheritance assumption of single trees. This representation is compact as it exploits the shared ancestry among genomes, representing each mutation only once on the branch where it arose instead of duplicating them across individual sequences.

In addition, PanMAN was crafted to represent a rich set of biologically meaningful information that current pangenome formats lack. Some information in PanMAN is explicitly stored, such as mutations, phylogeny, annotations, and root sequence, whereas other information can be derived, such as ancestral sequences, multiple whole-genome alignment, and genetic variation.

The researchers have used PanMAN to study microbial genomes. They have found that this method is the most compressible format among variation-preserving pangenomic formats, providing up to hundreds or even thousands of times more compression. For example, the team built the largest pangenome for SARS-CoV-2, using more than eight million separate genomes of the virus. Using their PanMAN method, this vast amount of genetic data only required 366MB of file storage space, which is roughly 3,000 times less storage than its corresponding whole-genome alignment that PanMAN encodes.

Now, the researchers are expanding their use of PanMANs from microbes to human genomes. “Extending compressive pangenomics to human genomes can fundamentally transform how we store, analyze, and share large-scale human genetic data,” said Turakhia. “Besides enabling studies of human genetic diversity, disease, and evolution at unprecedented scale and speed, it can depict detailed evolutionary and mutational histories which shape diverse human populations, something that current representations do not capture.”