One of society’s greatest medical challenges is to understand and develop effective treatments for disorders of intellectual disability (ID). Around 2–3 percent of the global population meet the criteria for ID.1 The condition is consistently more common in males. Recent U.S. data (2019–2021) indicate that 2.31 percent of boys and 1.37 percent of girls have been diagnosed with ID, a ratio of roughly 1.7:1.2

ID is not a single disease but rather a final common outcome of hundreds of genetic, chromosomal, and environmental conditions. Any attempt to catalogue these causes will necessarily be incomplete. Broadly, about a quarter of cases arise from identifiable genetic disorders, while a large fraction is linked to environmental factors such as prenatal alcohol exposure or perinatal complications. Between 30 and 50 percent remain idiopathic or non-syndromic, with no clear underlying cause identified.

Intellectual Disability Research Requires a Unified Strategy

Beyond its personal and social impact, ID carries a substantial financial burden. The lifetime cost per affected individual typically exceeds US $1 million, often more when adjusted for current prices, accounting for medical, educational, and productivity losses.3 The public, through taxpayer-funded systems, bears roughly one-third to one-half of this cost, while families shoulder the remainder through lost income, unpaid caregiving, and significant out-of-pocket expenses.4

Given these realities, there is an urgent need for medical science to deepen its understanding of ID and for the pharmaceutical industry to identify therapeutic solutions that can alleviate the burden, enhance quality of life, and ultimately lead to effective treatments. Governments also have a vital role to play. In April 2025, the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) wrote to the US Senate Appropriations Committee, noting that “95 percent of the > 10,000 known rare diseases still lack an FDA-approved treatment option” and urging that “robust funding for the NIH…is vital for addressing the tremendous unmet medical need.” 5

Such advocacy highlights that relying solely on non-profits, families, or private sector investment is insufficient. Federal research funding and taxpayer-supported therapeutic development are essential. Yet the diverse causes behind ID and the corresponding need for a wide range of therapeutic treatments make it difficult for governments to commit to a coherent, long-term funding strategy.

To better understand neurodevelopmental disorders, including intellectual disability, scientists should focus on the glutamatergic synapse as a central hub. Research on rare monogenic forms of intellectual disability, so-called synaptopathies involving genes that encode proteins at glutamatergic synapses, such as SYNGAP1, FMRP, and the genes encoding various ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits, has already revealed some of the key signaling proteins and molecular targets.6-11 These discoveries mark important milestones for the field. Yet a major challenge remains: to establish a unified conceptual framework that commands broad scientific consensus and offers the pharmaceutical industry a clear roadmap for developing effective therapies.

What is Intellectual Disability?

ID is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior with onset occurring during the developmental period, typically before the age of eighteen. These limitations affect the individual’s capacity to learn, reason, and engage independently in everyday activities. The definition emphasizes that ID is not merely a matter of low intelligence but a broader impairment in the ability to apply cognitive skills effectively within social and practical contexts.1

The assessment of ID relies on standardized measures of intellectual functioning, most commonly through intelligence quotient (IQ) testing. Scores of approximately 70 or below generally indicate significant impairment. However, diagnosis also depends on evaluating adaptive behavior, how well a person manages the conceptual, social, and practical demands of daily life. Conceptual skills include language, literacy, and numeracy; social skills encompass empathy, communication, and interpersonal responsibility; and practical skills involve self-care, work, and managing routines.

Individuals with mild ID are often able to live semi-independently with limited support, while those with moderate ID typically require daily assistance. Severe ID is characterized by extensive dependence on caregivers for most aspects of daily life, and profound ID involves complete reliance on others for care and supervision. This classification acknowledges that functional abilities vary widely, and that support must be tailored to individual strengths and challenges rather than rigid diagnostic categories.

The causes of ID are multifactorial, encompassing genetic, environmental, and biological factors. Genetic syndromes such as Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome represent well-defined causes, while prenatal exposures to infections, toxins, or malnutrition can interfere with brain development.12,13 Perinatal complications, such as oxygen deprivation during birth, and postnatal injuries or neglect can also contribute. Additionally, molecular and genetic mutations affecting neural communication or synaptic structure are increasingly recognized as major contributors, forming a link between the biological and environmental determinants of the disorder.

At the neurobiological level, ID reflects disturbances in brain development that affect reasoning, problem-solving, learning, and judgment. Increasing evidence links ID to dysfunctions in synaptic signaling, the way neurons communicate, particularly involving ionotropic glutamate receptors, such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs).14,12 These receptors play critical roles in learning and memory, and their disruption can lead to broad cognitive and behavioral impairments.13 Such findings have strengthened the view that ID arises from altered neurodevelopmental pathways rather than from a single defect or region of the brain.

Inside the Developing Brain

Early brain development is orchestrated by a complex web of genetic programs that guide the generation and organization of diverse cell types.14 These cells differentiate and migrate to form the distinct regions of the brain, establishing the structural blueprint for later function. Once these fundamental architectures are in place, the maturing brain undergoes an intense phase of refinement. The dynamic processes of connection, pruning, and reinforcement, driven largely by neurotransmitter activity and sensory experience, sculpts neuronal circuits.15,16 During this critical period, sensory inputs determine which synaptic connections are preserved and which are eliminated, shaping the brain’s functional networks that will support cognition, behavior, and perception throughout life.

In the mid-20th century, developmental neuroscientists began exploring how chemical signaling contributes to these processes. By applying pharmacological blockers to neural tissue, they identified L-glutamic acid (L-Glu), an excitatory amino acid, as a key neurotransmitter governing synaptic communication.17 This discovery marked a turning point in the understanding of how neurons communicate and adapt during development. The identification of L-Glu as a primary excitatory signal paved the way for molecular investigations into the receptors that mediate its effects.

Subsequent breakthroughs in molecular biology enabled the cloning of genes encoding the various subunits of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), the receptors directly activated by L-Glu.18-20 This allowed scientists to classify iGluRs into distinct families based on their structure, function, and pharmacology and to map their roles in brain development. Two receptor families emerged as central to this process: NMDARs and AMPARs. Together, they form the cornerstone of excitatory neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity in the developing brain.13,21

NMDARs serve as primary carriers of calcium (Ca²⁺) signals within neurons. Activation of these receptors triggers a cascade of Ca²⁺-dependent biochemical events that drive long-lasting changes in the structure and function of excitatory synapses. However, at resting membrane potentials, NMDAR channels are tonically blocked by magnesium (Mg²⁺) ions, preventing their activation. AMPARs, which are often co-expressed with NMDARs at the same synapses, play a critical complementary role. When L-Glu is released into the synaptic cleft, AMPARs open rapidly to allow sodium influx and depolarize the postsynaptic membrane. This depolarization removes the Mg²⁺ block from NMDARs, enabling Ca²⁺ entry. Through this arrangement, NMDARs act as coincidence detectors, responding only when presynaptic neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic depolarization occur simultaneously, thereby strengthening synapses that are functionally relevant.

Further research by synaptic physiologists revealed that glutamatergic synapses are not static structures but undergo enduring modifications known as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD).22,23 These processes, dependent on NMDAR and AMPAR signaling, represent cellular mechanisms thought to underlie learning and memory. The discovery of LTP and LTD established a direct link between molecular synaptic mechanisms and higher cognitive functions, underscoring the centrality of glutamatergic signaling to brain development and function.

AMPARs Enable Brain Circuits to Perform Neuronal Arithmetic

Neuronal arithmetic, the process by which neurons integrate and compute synaptic inputs, relies on the precise interplay between presynaptic neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic receptor function. On the presynaptic side, the reliability of neurotransmitter release determines how consistently signals are transmitted. On the postsynaptic side, the properties of AMPARs largely define how those signals are interpreted and transformed into electrical and biochemical responses.24 Together, these mechanisms allow neuronal circuits to perform complex computations that underlie perception, learning, and behavior.

A critical determinant of how AMPARs influence neuronal computation is their subunit composition. AMPARs can either act as faithful translators, accurately conveying presynaptic inputs to postsynaptic neurons, or as low-pass filters that integrate or dampen rapid input signals. Which mode they adopt depends on the molecular architecture of the receptor and its associated proteins. Although many of these molecular mechanisms remain under investigation, several key principles have become clear from recent research.

At the structural level, AMPARs are tetrameric complexes composed of four pore-forming subunits, known as GluA1 through GluA4. These core subunits assemble with a range of auxiliary proteins that finetune their trafficking, gating, and kinetic properties.25 Each AMPAR typically co-assembles with at least two Transmembrane AMPAR Regulatory Proteins (TARPs), which modulate receptor localization and conductance. Other auxiliary subunits, including Cornichon homologs (CNIHs), cysteine‐knot AMPAR modulating proteins/Shisa proteins, and Synapse Differentiation Induced Gene family proteins, provide additional layers of regulatory control. While the fundamental rules governing this assembly are not yet fully elucidated, it is clear that different combinations of auxiliary subunits yield receptors with distinct properties across cell types and synaptic environments. This molecular diversity allows neurons to tailor their AMPAR-mediated responses to the specific computational demands of each circuit.

Beyond structural assembly, AMPAR function is further diversified by post-transcriptional regulation. Each subunit undergoes a range of molecular modifications that alter receptor kinetics and ion permeability. One of the most important mechanisms is alternative splicing of the so-called flip/flop cassette within the receptor’s RNA sequence.29 The flip variant enhances regulation by TARP subunits, while the flop variant suppresses such modulation, effectively acting as a molecular switch.26,27 Another key process is RNA editing, which can profoundly alter receptor properties. Editing at the Q/R site within the pore of the GluA2 subunit, for instance, determines Ca²⁺ permeability: the edited (arginine, R) version blocks Ca²⁺ entry, while the unedited (glutamine, Q) form allows it.32,33 Co-assembly with TARPs or CNIHs modify this effect further, creating a continuum of Ca²⁺ conductance rather than a simple on/off state.34, 28 Although the functional significance of RNA editing at another site, the R/G site, remains unclear, its presence adds yet another dimension to receptor plasticity.36

Taken together, these layers of molecular, post-transcriptional, and developmental regulation enable AMPARs to function as dynamic computational elements within neuronal networks. By integrating signals with exquisite temporal and spatial precision, AMPARs help transform neural activity into the complex computations that underlie cognition and behavior.

Dissecting the Genetic Landscape of AMPAR Dysfunction

Despite major advances in our understanding of AMPARs, there remains no clear explanation for why nearly 100 missense mutations in genes encoding their subunits (GRIA1–GRIA4) give rise to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ID (Fig. 1). From the genetic and functional data collected to date, two prominent features nevertheless emerge.

Figure 1. Missense mutations identified in GRIA genes associated with intellectual disability (ID). All four GRIA genes, which encode the AMPA-type glutamate receptor (AMPAR) subunits, have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders involving ID. Notably, nearly half of all reported missense variants occur in the X-linked GRIA3 gene, which encodes the GluA3 subunit (pie chart, left). In contrast to the GRIN genes that encode NMDA receptor subunits, missense mutations in AMPARs are distributed across the entire receptor structure (center), rather than clustering within specific domains—though this observation awaits more comprehensive residue-level functional analyses.

Figure courtesy of Amanda Perozzo. Design Updates by: Janette Lee-Latour

First, missense mutations are distributed throughout the AMPAR structure, suggesting that disruption of multiple receptor processes, including gating, ion permeation, and trafficking, can each contribute to neurodevelopmental pathology.29 Consistent with this idea, a comprehensive recent analysis demonstrated that all 52 missense variants examined produced measurable alterations in one or more fundamental receptor properties, including agonist EC₅₀, response kinetics, desensitization, and surface expression.29 These findings indicate that pathogenicity arises not from a single structural hotspot, but from cumulative perturbations in the receptor’s allosteric and signaling architecture.

A second notable pattern concerns the relative frequency of mutations across AMPAR subunits. Although GRIA1 and GRIA2 dominate AMPAR expression in both developing and mature central nervous systems, GRIA3 contributes disproportionately to known cases of ID.38,39 This is unexpected given that GluA3 typically co-assembles with GluA2 to form A2/A3 heteromers rather than the predominant A1/A2 combination. A plausible explanation lies in genetics: The GRIA3 gene resides on the X chromosome, predisposing hemizygous males to pathogenic expression of mutant alleles. Functional analysis of GRIA3 variants has revealed strikingly similar biophysical consequences to those observed in GRIA1, GRIA2, and the larger GRIA family, suggesting a shared pathophysiological mechanism across subunits.40-42,37

Does a Common Mechanism Link AMPAR Missense Mutations to ID

Given the diversity of pathogenic variants, two interrelated mechanisms may be considered to provide a unifying framework to understand how AMPAR mutations produce ASD and ID phenotypes.

The first relates to the complicated interaction between channel gating and Ca²⁺ permeability in AMPARs. It is now known that native AMPARs form a continuum of ion channels with different degrees of Ca²⁺ permeability.28,30 They achieve this by coordinating Ca²⁺ ion transport between two distinct binding sites: the Q/R site within the pore’s selectivity filter and a novel extracellular site, termed Site-G, which also contributes to the channel gate.31 Interestingly, amino acid residues critical for Ca²⁺ transport are also essential for channel gating. For example, the N-K mutation that causes severe epilepsy associated with ID not only forms a Ca²⁺-binding site at Site-G to funnel Ca²⁺ into the Q/R site of the channel pore, but also serves as an intrinsic component of the channel gate that determines the time course of synaptic signaling.31 This mutation allows the channel to open even in the absence of neurotransmitter, potentially accounting for its tendency to cause seizures, yet it is poor at transporting Ca²⁺, a property likely to contribute to broader dysfunctions in brain activity.

Conversely, a recent study has shown that mutations within the ion channel pathway can give rise to greater Ca²⁺ permeability, suggesting that there is an upper limit to the amount of Ca²⁺ transport that can be tolerated in mammalian neurons by AMPARs.30 This observation agrees well with earlier work demonstrating that alterations in Ca²⁺ permeability of AMPARs can have devastating consequences for both the developing and adult central nervous system, leading in extreme cases to seizures and death.32,33 Consequently, it may be that the clinical consequences of some missense mutations linked to deficits in channel gating also involve dysfunctions in Ca²⁺ transport, either too little or too much. This idea has yet to be fully explored, but it is now well within reach of the research community.

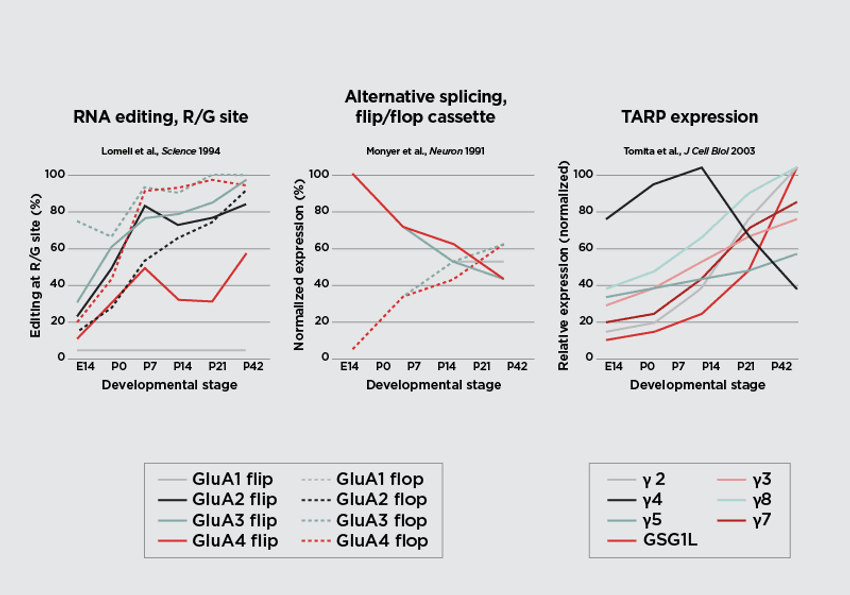

The second possibility is that missense mutations disrupt the post-transcriptional programs that dynamically regulate AMPAR subunit composition during brain development. In particular, these variants may interfere with the timing of RNA editing at the R/G site and/or alternative splicing of the flip/flop cassette, as well as the coordinated expression of auxiliary subunits (Fig. 2).29,36,38,46 Together, these disturbances could alter the normal pattern of AMPAR assembly across the brain, compromising the receptors’ ability to perform the complex “neuronal arithmetic” required for proper synaptic integration.

Figure 2. Dynamic regulation of post-transcriptional modification and auxiliary protein expression of AMPAR subunits during brain development. RNA editing at the R/G site of GRIA transcripts increases across development for all AMPAR subunits except GluA1(left). During the embryonic stages, most AMPAR subunits are expressed as the “flip” isoform, with a progressive shift toward the “flop” isoform as the brain matures (center). Expression of transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs) and GSG1L also increases throughout development, except for TARP γ4, which is highly expressed early in development and declines thereafter.

Figure courtesy of Chloe Koens. Design Updates by: Janette Lee-Latour

Although this hypothesis has yet to be formally tested, it presents a compelling, testable mechanism that could account for many of the nearly one hundred GRIA missense mutations linked to ASD and ID. The precise role of the R/G site in this framework remains uncertain, but if it is found to interface with the properties of AMPAR auxiliary subunits, such an interaction would lend additional support to this unifying model.

NMDARs Act as Coincidence Detectors in Neuronal Circuits

NMDARs serve as critical coincidence detectors in neuronal circuits, integrating presynaptic glutamate release with postsynaptic depolarization to regulate synaptic plasticity. Unlike AMPARs, whose functional diversity depends largely on auxiliary subunits, the diversity of NMDAR functionality arises primarily from changes in receptor subunit composition within the obligate di- or tri-heteromeric channels that assemble across the developing and adult brain.13,34,35 This subunit variability enables NMDARs to fine-tune neuronal computation, synaptic integration, and circuit dynamics throughout life.

The principal role of NMDARs is to mediate Ca²⁺ influx into glutamatergic synapses, where Ca²⁺ acts as a key second messenger initiating long-lasting biochemical cascades that modify both synaptic efficacy and neuronal structure.36 This unique capacity underlies core forms of synaptic plasticity, including LTP and LTD, which are central to learning and memory.

These properties are primarily executed by “conventional” NMDARs, which are typically composed of two GluN1 and two GluN2 (A–D) subunits. The GluN1/2 assemblies form glycine- and glutamate-gated ion channels exhibiting hallmark features such as voltage-dependent Mg²⁺ block, high Ca²⁺ permeability, and slow deactivation kinetics.34,35 Among these, GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors—predominant in the adult central nervous system—display the strongest Mg²⁺ block and greatest Ca²⁺ conductance, whereas GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing receptors exhibit weaker block and lower Ca²⁺ permeability.34 Such subunit-specific properties confer distinct temporal and voltage-sensitivity profiles, allowing NMDARs to perform precise coincidence detection across different neuronal types and brain regions.

This molecular architecture provides the mammalian brain with a remarkable degree of functional flexibility. Beyond the canonical GluN1/2 receptors, additional diversity arises from the “unconventional” or atypical NMDARs that incorporate GluN3 subunits—GluN3A (encoded by GRIN3A) and GluN3B (GRIN3B). These subunits were identified later, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and can co-assemble with GluN1, either with or without GluN2, to generate distinct receptor populations.37

GluN1/GluN3 diheteromeric receptors are unique in that they are activated solely by glycine, not glutamate. They lack the characteristic Mg²⁺ block of conventional NMDARs and are impermeable to Ca²⁺, representing a fundamental shift in signaling modality. In contrast, triheteromeric GluN1/GluN2/GluN3 receptors retain some classical NMDA receptor properties but exhibit reduced Ca²⁺ permeability and a diminished Mg²⁺ block, thereby broadening the physiological range of excitatory synaptic responses.

Together, the array of possible NMDAR configurations, ranging from highly Ca²⁺-permeable GluN2A/B assemblies to modulatory GluN3-containing complexes, provides neuronal circuits with a versatile toolkit for controlling excitatory drive, timing, and plasticity. This molecular and functional heterogeneity underpins the receptor’s dual role as both a coincidence detector and a regulator of long-term synaptic remodeling, making NMDARs central to the adaptability and computational power of the mammalian brain.

Missense Mutations in NMDA Receptors

Missense mutations in NMDARs have been broadly classified into gain-of-function (GoF) and loss-of-function (LoF) categories, reflecting how they either enhance or impair receptor activity. Despite extensive understanding of the varied subunit composition of NMDARs, much of the evidence linking them to ID has focused on the more abundant conventional receptors containing GluN2A and/or GluN2B subunits.

To date, estimates of missense variants affecting genes that encode the GluN1 and GluN2A–D subunits vary, but recent genomic surveys suggest there are at least 400 such variants identified across patient and population datasets.38,39 Many of these variants have been found not only in individuals with ID but also in patients with ASD, epilepsy, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenia, highlighting NMDAR dysfunction as a common molecular hub across neuropsychiatric disorders.40

Genetic and functional studies have revealed distinct contributions of GRIN2A and GRIN2B variants to neurological disease.41 Clinically, GRIN2A mutations are more frequently associated with epileptic phenotypes, whereas GRIN2B variants are predominantly linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, including intellectual disability. These findings underscore the distinct physiological roles of each subunit in synaptic circuit function and emphasize the need for further functional characterization of GRIN2A and GRIN2B variants to refine the subclassification of clinical phenotypes.41

Although GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors were once thought to share similar allosteric mechanisms, structural studies have now demonstrated that they utilize distinct long-range allosteric pathways, involving different subunit interfaces and molecular rearrangements.42 In GluN2A-containing receptors, allosteric coupling primarily occurs between N-terminal domain (NTD) dimers and through the agonist-binding domain (LBD) intra-dimer interface (D1–D1). By contrast, GluN2B receptors rely more on within-dimer rearrangements and the LBD inter-dimer interface. Moreover, GluN2B receptors exhibit greater structural flexibility, with their NTDs sampling larger conformational motions than those of GluN2A, conferring unique pharmacological sensitivities.42

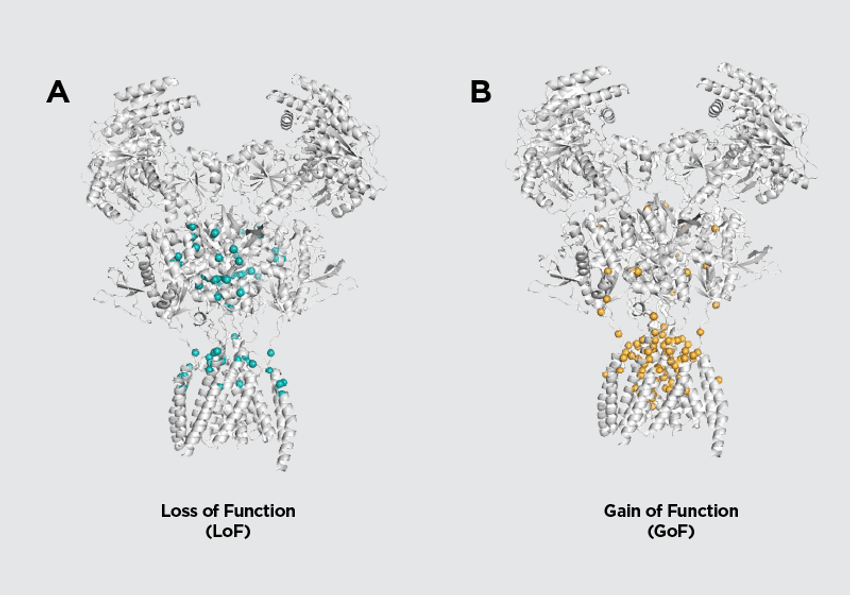

A recent comprehensive analysis of NMDAR missense variants integrated computational predictions with electrophysiological testing to classify mutations as GoF or LoF (Fig. 3).51 By mapping 832 variants from GRIN1, GRIN2A, and GRIN2B onto high-resolution receptor structures, Montanucci and colleagues demonstrated that benign variants are typically located farther from functional regions, such as the ion pore and ligand-binding pockets, whereas pathogenic variants cluster near glutamate, glycine, Mg²⁺, or Zn²⁺ binding sites. Functionally, LoF variants localize near the glutamate-binding cleft, disrupting agonist activation, while GoF variants are enriched near Mg²⁺ and transmembrane regions, where altered voltage-dependent block or gating enhances receptor activity. These spatial patterns enabled the development of machine-learning models that can accurately predict variant pathogenicity and functional directionality based on 3D ligand proximity.38

Figure 3. Loss and gain of function NMDAR variants occupy different locations on the tetramer structure. Mapping variants of GRIN1, GRIN2A, and GRIN2B genes onto high-resolution NMDAR structures reveals that LoF variants localize near the glutamate-binding cleft whereas GoF variants are enriched near the pore and transmembrane regions.

Figure adapted from Montanucci et al (2025). Design Updates by: Janette Lee-Latour

This emerging understanding has direct therapeutic relevance. Patients with GoF variants may benefit from negative allosteric modulators, whereas those with LoF variants could respond to positive modulators that enhance receptor activity. This framework has guided the design of clinical interventions, including an ongoing trial evaluating radiprodil, a selective GluN2B negative allosteric modulator, for the treatment of GoF-associated GRIN disorders.43

The Matrix of Proteins of the Glutamatergic Synapse

Beyond the ion channels of the synapse, it has become clear that deficits in many other proteins essential for the normal function of glutamatergic synapses are linked to the occurrence of ID.

As noted above, these include ionotropic receptor genes such as GRIA1–4 and GRIN1, GRIN2A, and GRIN2B, as well as the less common GRIN2C, GRIN2D, GRIN3A, and GRIN3B genes.44 Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) have also been implicated. Most notably, the GRM7 gene, which encodes the group III metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR7, has been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders featuring ID.45 To date, mGluR7 remains the only metabotropic glutamate receptor directly linked to ID, although earlier studies implicated mGluR5 dysfunction in the ID associated with Fragile X syndrome.46,47

A large group of proteins that make up the postsynaptic density (PSD) scaffold and its associated signaling machinery have also been implicated. Scaffolding proteins such as PSD-95, SHANK3, and SYNGAP1 play crucial roles in maintaining excitatory synaptic structure and signaling and are linked to Phelan-McDermid syndrome and SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability, respectively.61-64 Signaling proteins associated with ID include the Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent kinases IIα and IIβ (CAMK2A and CAMK2B), which are major kinases at excitatory synapses involved in LTP and LTD. De novo and recessive mutations in CAMK2A and CAMK2B cause neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by growth delay, seizures, and severe ID.48

The final group of proteins to consider are those that form the numerous cell-adhesion complexes essential for the organization and maintenance of glutamatergic synapses. Among the most studied are the neurexins, such as Neurexin-1, encoded by the NRXN1 gene, which serve as presynaptic adhesion molecules and key organizers of glutamatergic release sites.49,50 Exon deletions in NRXN1 give rise to a broad spectrum of neurodevelopmental symptoms, including ASD, ID, language delays, and hypotonia.51 On the postsynaptic side, the neuroligins have similarly been implicated in ASD and ID. These adhesion molecules exist as multiple isoforms (NLGN1–4), which are both autosomal and sex-linked. The X-linked genes NLGN3 and NLGN4, encoding Neuroligin-3 and Neuroligin-4, were among the first to be identified as contributors to ASD and ID.52 Missense variants in NLGN3 cause nonsyndromic ID with ASD, and similar findings have been reported for Neuroligin-4.53-55

The link between ID and dysfunction of the glutamatergic synapse is now compelling. From the earliest investigations uncovering the molecular underpinnings of the developing brain to the more recent advances in whole-genome sequencing, research has revealed a wealth of genetic variants that disrupt the normal function of the ion channels, structural proteins, and signaling molecules that define the glutamatergic synapse. Despite this remarkable progress, few translational studies have been designed to target glutamatergic synaptic deficits a priori. Instead, most therapeutic efforts have arisen serendipitously and, to date, have yielded limited success.

Targeting LoF and GoF GRIN mutations with positive and negative allosteric modulators represents a promising first step, but such approaches may face challenges of specificity, as functional impairments are likely to be more cell-type restricted, potentially confined to subsets of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. At the clinical level, greater emphasis is needed on evaluating drug efficacy using biomarkers derived from objective, empirical measurements rather than relying primarily on psychometric assessments or self-reporting.

Ultimately, meaningful progress will require a coordinated strategy that extends beyond the laboratory and clinic. There is an urgent need for national governments to develop directed funding frameworks that harness the combined expertise of biomedical researchers, clinicians, advocacy foundations, families and individuals with lived experience. Each stakeholder holds unique insight that, if integrated, could define a clear and effective path forward: one that can overcome past missteps and creating the conditions necessary to treat, and perhaps one day cure, ID.

- Daily DK, et al. Identification and evaluation of mental retardation. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(4):1059-67.

- Zablotsky B, et al. Diagnosed Developmental Disabilities in Children Aged 3-17 Years: United States, 2019-2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023;(473):1-8.

- Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Economic costs associated with mental retardation, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and vision impairment–United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(3):57-9.

- Crawford C. Learning Disabilities in Canada: Economic Costs to Individuals, Families and Society. 2007:1-49.

- Letter to the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations regarding FY 2026 NIH funding. 1-5 (2025).

- Zoghbi HY, Bear MF. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with autism and intellectual disabilities. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(3):a009886.

- Grant SG. Synaptopathies: diseases of the synaptome. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22(3):522-9.

- Verpelli C, Sala C. Molecular and synaptic defects in intellectual disability syndromes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22(3):530-6.

- Volk L, et al. Glutamate synapses in human cognitive disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:127-49.

- Moretto E, et al. Glutamatergic synapses in neurodevelopmental disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(Pt B):328-342.

- Bagni C, Zukin RS. A Synaptic Perspective of Fragile X Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron. 2019;101(6):1070-1088.

- Tvergaard NK, et al. Unraveling GRIA1 neurodevelopmental disorders: Lessons learned from the p.(Ala636Thr) variant. Clin Genet. 2024;106(4):427-436.

- Hansen KB, et al. Structure, Function, and Pharmacology of Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):298-487.

- Harris WA. Zero to Birth: How the Human Brain Is Built. Princeton University Press; 2022.

- Constantine-Paton M, et al. Patterned activity, synaptic convergence, and the NMDA receptor in developing visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:129-54.

- Aamodt SM, Constantine-Paton M. The role of neural activity in synaptic development and its implications for adult brain function. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:133-44.

- Evans RH, Watkins JC. Team Evans and Watkins: Excitatory Amino Acid research at Bristol University 1973-1981. Neuropharmacology. 2021;198:108768.

- Seeburg PH. The TINS/TiPS Lecture. The molecular biology of mammalian glutamate receptor channels. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16(9):359-65.

- Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31-108.

- Nakanishi S. Molecular diversity of glutamate receptors and implications for brain function. Science. 1992;258(5082):597-603.

- Dingledine R, et al. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(1):7-61.

- Nicoll RA, Schulman H. Synaptic memory and CaMKII. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(4):2877-2925.

- Collingridge GL. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus: From magnesium to memory. Neuroscience. 2025;578:126-131.

- Silver RA. Neuronal arithmetic. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(7):474-89.

- Greger IH, et al. Structural and Functional Architecture of AMPA-Type Glutamate Receptors and Their Auxiliary Proteins. Neuron. 2017;94(4):713-730.

- Dawe GB, et al. Nanoscale Mobility of the Apo State and TARP Stoichiometry Dictate the Gating Behavior of Alternatively Spliced AMPA Receptors. Neuron. 2019;102(5):976-992 e5.

- Perozzo AM, et al. Alternative Splicing of the Flip/Flop Cassette and TARP Auxiliary Subunits Engage in a Privileged Relationship That Fine-Tunes AMPA Receptor Gating. J Neurosci. 2023;43(16):2837-2849.

- A textbook assumption about the brain’s most abundant receptors needs to be rewritten. Nature. 2025.

- XiangWei W, et al. Clinical and functional consequences of GRIA variants in patients with neurological diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(11):345.

- Miguez-Cabello F, et al. GluA2-containing AMPA receptors form a continuum of Ca(2+)-permeable channels. Nature. 2025;641(8062):537-544.

- Nakagawa T, et al. The open gate of the AMPA receptor forms a Ca(2+) binding site critical in regulating ion transport. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024;31(4):688-700.

- Higuchi M, et al. Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2. Nature. 2000;406(6791):78-81.

- Feldmeyer D, et al. Neurological dysfunctions in mice expressing different levels of the Q/R site-unedited AMPAR subunit GluR-B. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(1):57-64.

- Paoletti P, et al. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(6):383-400.

- Hansen KB, et al. Structure, function, and allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors. J Gen Physiol. 2018;150(8):1081-1105.

- Herring BE, Nicoll RA. Long-Term Potentiation: From CaMKII to AMPA Receptor Trafficking. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:351-65.

- Stroebel D, et al. Glycine agonism in ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2021;193:108631.

- Montanucci L, et al. Ligand distances as key predictors of pathogenicity and function in NMDA receptors. Hum Mol Genet. 2025;34(2):128-139.

- Cha JH, et al. Exploring gene-phenotype relationships in GRIN-related neurodevelopmental disorders. NPJ Genom Med. 2025;10(1):40.

- Hanson JE, et al. Therapeutic potential of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor modulators in psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2024;49(1):51-66.

- Myers SJ, et al. Distinct roles of GRIN2A and GRIN2B variants in neurological conditions. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000.

- Tian M, et al. GluN2A and GluN2B NMDA receptors use distinct allosteric routes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4709.

- Banke TG, et al. Inhibition of GluN2B-containing N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors by radiprodil. Brain. 2025:awaf355.

- XiangWei W, et al. De Novo Mutations and Rare Variants Occurring in NMDA Receptors. Curr Opin Physiol. 2018;2:27-35.

- Fisher NM, et al. A GRM7 mutation associated with developmental delay reduces mGlu7 expression and produces neurological phenotypes. JCI Insight. 2021;6(4):e143324.

- Bear MF, et al. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(7):370-7.

- Krueger DD, Bear MF. Toward fulfilling the promise of molecular medicine in fragile X syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:411-29.

- Kury S, et al. De Novo Mutations in Protein Kinase Genes CAMK2A and CAMK2B Cause Intellectual Disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(5):768-788.

- Sudhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455(7215):903-11.

- Connor SA, Siddiqui TJ. Synapse organizers as molecular codes for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46(11):971-985.

- Ching MS, et al. Deletions of NRXN1 (neurexin-1) predispose to a wide spectrum of developmental disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(4):937-47.

- Nguyen TA, et al. Neuroligins and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: X-Linked Genetics. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2020;12:33.

- Quartier A, et al. Novel mutations in NLGN3 causing autism spectrum disorder and cognitive impairment. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(11):2021-2032.

- Redin C, et al. Efficient strategy for the molecular diagnosis of intellectual disability using targeted high-throughput sequencing. J Med Genet. 2014;51(11):724-36.

- Jamain S, et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):27-9.