The rapid rise of biosimilars is reshaping retinal therapeutics, and manufacturing science is increasingly central to that shift. As Ashish Sharma, MD, a consultant in retinal research at the Lotus Eye Hospital and Institute in Coimbatore, India, and colleagues explain, ranibizumab biosimilars have already “led the way over the past few years across various global markets,” while newly approved aflibercept biosimilars are poised to follow. Beneath regulatory milestones, however, lie profound differences in how these molecules are made—differences that might ultimately influence adoption, pricing, and patient access.

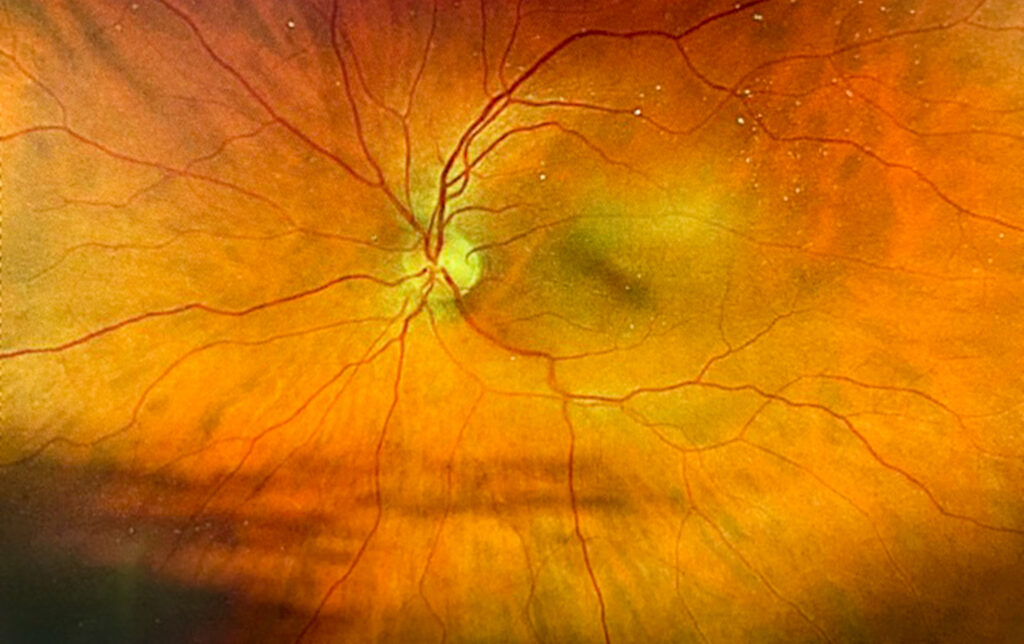

Both drugs target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a family of signaling proteins that promote blood-vessel formation and increase vascular permeability. In retinal diseases, pathological overexpression of VEGF drives abnormal neovascularization and fluid leakage, leading to vision loss. Anti-VEGF therapies work by neutralizing this pathway, but they do so by using structurally distinct molecules that demand very different manufacturing approaches.

Ranibizumab is a humanized antibody fragment composed only of the Fab portion of IgG1 and lacks an Fc region. Its relatively small size makes it amenable to bacterial expression, most commonly in Escherichia coli. Yet, as the authors note, “expressing active protein in E. coli is technically challenging, particularly for complex proteins like ranibizumab.” Correct folding of light and heavy chains, along with precise disulfide bond formation, is difficult to achieve in bacterial systems. This often results in inclusion bodies—insoluble aggregates that require laborious solubilization, oxidative refolding, and purification steps. Even when periplasmic expression is used to obtain soluble protein, yields are typically modest, and process variability can affect consistency.

Aflibercept, by contrast, is a recombinant fusion glycoprotein that combines VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 domains with the Fc region of human IgG1. Its complexity necessitates a mammalian expression system, and Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells have become the platform of choice. CHO cells enable proper folding, glycosylation, and secretion of aflibercept in its active form directly into the culture medium. This design “eliminates the need for refolding,” reducing manufacturing complexity and potential variability. Downstream processing is comparatively straightforward, relying on affinity and interaction chromatography followed by filtration.

These divergent platforms have clear implications for yield and cost. Aflibercept expression in CHO cells is “fairly high,” with a controlled process designed to meet a defined quality target product profile. Ranibizumab manufacturing, particularly when inclusion bodies are involved, is more resource-intensive and less predictable.

Ultimately, as Sharma and colleagues conclude, manufacturing efficiency might be as important as clinical equivalence in shaping biosimilar uptake. Given aflibercept’s dominant market share among retina specialists, its biosimilars—supported by scalable CHO-based production—might accelerate competition, reduce costs, and expand access, turning biomanufacturing excellence into tangible benefits for patients and healthcare systems alike.