Identifying the root of any given disease is often the first step in developing effective therapies. Neurodegenerative diseases are notoriously difficult to study and treat. Conditions like multiple sclerosis—an autoimmune disease characterized by myelin degradation—are especially challenging to test in vivo.

A team at Johns Hopkins Medicine led by Dwight Bergles, PhD, has focused their work on myelin development using oligodendrocytes. While oligodendrocyte precursor (OPCs) are the largest population of progenitor cells in the adult brain, their differentiation mechanisms are not well understood.

“OPCs are fascinating because they enable one of the longest developmental programs in the brain,” Bergles told GEN. “We were motivated to try to understand this process, as a way to increase their differentiation to enhance remyelination in disease states like multiple sclerosis.”

Using a variety of techniques, the team focused on determining how OPCs differentiate into new oligodendrocytes. They used a combined approach including analyzing gene expression in multiple species (including mice, marmosets and humans), determining localization of proteins in brain tissue, and using time lapse microscopy in the brains of live mice to follow OPC differentiation.

Bergles explained, “This multifaceted approach gives us greater confidence in the conclusions, as it did not depend on one method alone.”

The culmination of their work was published in Science in a paper titled: “Myelin is repaired by constitutive differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors.”

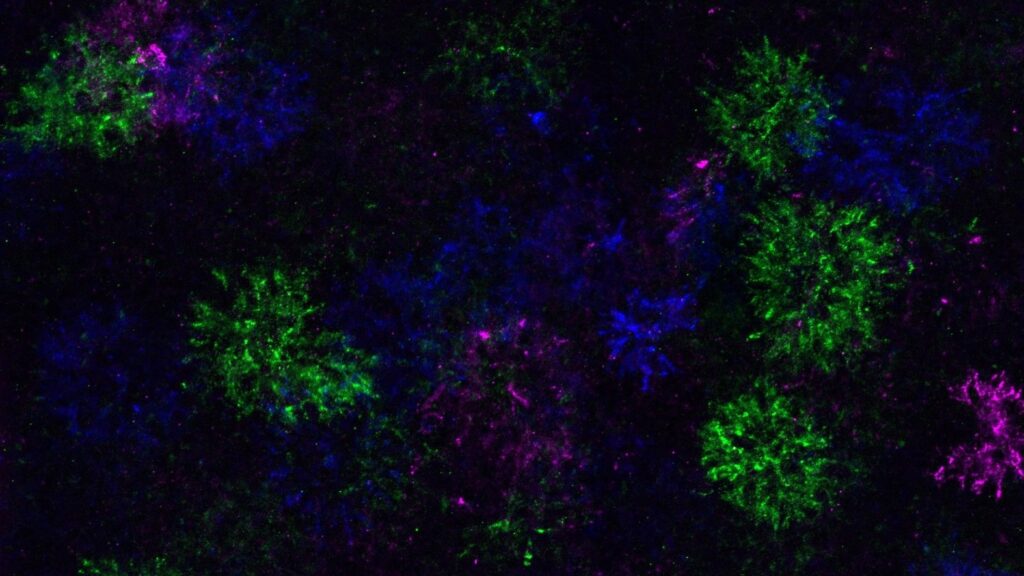

During differentiation, OPCs change not only their own gene expression, but also modify the surrounding extracellular matrix. These changes result in the formation of “dandelion clock-like structures,” or DACS. “This understanding gives us a new way to study where and when this happens in the brain, a question that was not possible to answer before,” Bergles told GEN.

Using time lapse imagery in live mice enabled tracking of the DACs through differentiation. Through this analysis, the team found that “OPCs were attempting to differentiate all over the brain, even in regions where they will never be able to form oligodendrocytes,” suggesting that differentiation is intrinsically controlled by the OPCs, and not instigated by external factors, like the loss of other oligodendrocytes.

To test the impacts of disease, trauma, and aging on the brain, the team mimicked myelin-related disease by removing oligodendrocytes and myelin in mouse brains. They found that the rate and location of OPC differentiation was not changed in these animals.

“We often talk about myelin ‘regeneration’ or ‘repair,’ but our studies suggest that what happens is simply a continuation of developmental myelination,” Bergles commented to GEN. “These results suggest that there isn’t a repair process for myelin in the brain, and that our ability to reform oligodendrocytes is because the developmental program for production of new oligodendrocytes continues into adulthood.”

Bergles continued, stating that these results have implications for the study of diseases of myelin loss, like multiple sclerosis, since there is no targeted regenerative mechanism. Further, their work showed that the rate of differentiation slows with age, which may lead to increasing disability in individuals with such conditions as they age.

While this study fills in a large gap in understanding the function and development of OPCs in the brain, Bergles was clear that there is much more still to come.

“We are excited about exploring why OPCs change the surrounding extracellular matrix just when they start to differentiate. They undergo an elaborate change in gene expression to allow this matrix alteration to occur, but we don’t know yet why they do this.”

Not only will his team continue to work on the mechanism behind early differentiation, but there are still questions related to the survival of differentiation oligodendrocytes, as they were noted to begin development in areas of the brain that did not retain the fully differentiated oligodendrocytes.

“The mechanisms that control this later step in oligodendrocyte differentiation are not known but could provide us with new ways to restore normal myelin patterning in developmental disorders and to more efficiently reform oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis,” Bergles explained.

Bergles highlighted how his team worked diligently to develop new techniques to study the brain in vivo. “Science is a team effort, and this project exemplifies how diverse perspectives can lead to unexpected new insights about brain development and repair.”