Researchers from Singapore’s A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (A*STAR IMCB) report that they have identified why certain lung cancer cells become highly resistant to treatment after developing mutations in the EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) gene. In a study “A genome-wide genetic screen reveals the P2Y2-integrin axis as a stabilizer of EGFR mutants in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)” published in Science Advances, the team revealed a previously unknown survival mechanism and demonstrated that disrupting it can shrink tumors in laboratory models.

Many lung cancer cases are driven by mutations in the EGFR gene. In Southeast Asia, these mutations appear in up to 40–60% of adenocarcinoma. While targeted drugs initially work well against these cancers, nearly all patients eventually stop responding.

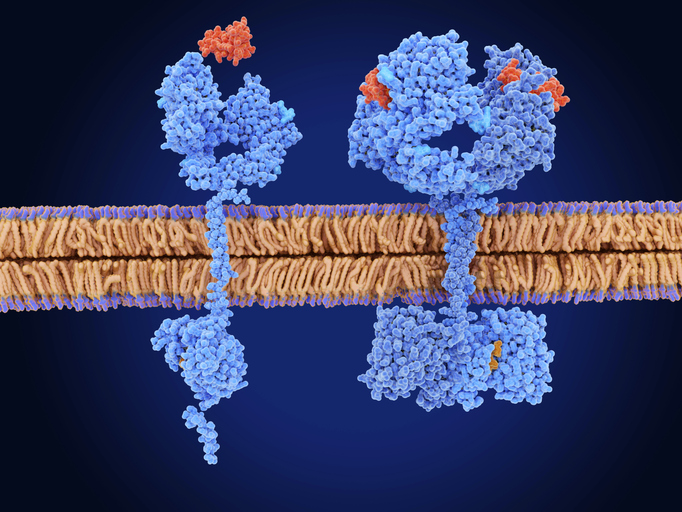

Scientists have long puzzled over why the faulty proteins produced by mutant EGFR are so stable, while normal proteins are recycled via degradation. These mutant versions persist far longer than they should.

Genome-wide screen

The investigators screened more than 21,000 genes to identify what protects these mutant proteins from being broken down. They discovered that cancer cells flood their surroundings with ATP, a molecule normally used for energy. This excess ATP switches on the P2Y2, which then recruits a partner protein, integrin β1, to form a protective barrier around the mutant EGFR.

The barrier stops the faulty protein from reaching the cell’s recycling center. Instead, the protected protein remains active and continues to drive cancer growth. The team confirmed these findings in human cancers by examining tissue samples from 29 lung cancer patients, where both P2Y2 and integrin β1 were found at elevated levels in tumors compared to adjacent healthy tissue.

“We found that cancer cells deploy molecular ‘bodyguards’ to shield the mutant protein from being broken down,” said Gandhi Boopathy, PhD, senior scientist at A*STAR IMCB and co-corresponding author of the study. “The good news is that P2Y2 sits on the cell surface, so it’s much easier for drugs to reach compared to targets hidden deep inside the cell.”

The researchers showed that removing this protective system could stop cancer in its tracks. When they knocked out the P2Y2 receptor in drug-resistant cancer cells, it led to an almost complete loss of the mutant EGFR protein.

The scientists also tested kaempferol, a natural compound found in vegetables like kale and broccoli. In laboratory models with drug-resistant human lung tumors, daily treatment with kaempferol significantly shrank tumors over 24 days. The treatment targeted only the cancer cells carrying EGFR mutations while having no detectable effect on tumors with normal EGFR.

“By targeting the P2Y2 system, we’re not just attacking the mutation itself, but the scaffolding that keeps it stable,” explained Wanjin Hong, PhD, senior principal investigator at A*STAR IMCB and co-corresponding author. “This approach could potentially work alongside current drugs to overcome or even prevent resistance, opening up a new way to tackle drug resistance when existing treatments stop working.”