New research identifies a regulator that helps the brain use amyloid assembly in a controlled way – with implications for cognitive aging.

Some memories dissolve before they have even finished forming; others arrive with a click of permanence, as though the brain has decided they deserve shelf space for life. A new study from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research, led by Scientific Director and neuroscientist Kausik Si, PhD, tackles a long-standing mystery behind that selectivity – and does so by rehabilitating one of biology’s most notorious substances.

The work centers on amyloids, the tightly packed protein assemblies most commonly associated with Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease. Yet amyloid-like structures are also known to play a physiological role in the brain, supporting long-term memory in at least some animals. The question has been awkwardly simple: if amyloid assembly can be useful, how does the nervous system stop it becoming destructive?

Longevity.Technology: We have spent the better part of two decades treating amyloid as biology’s equivalent of a bad guest – loud, sticky and impossible to get out of your house – and then acting surprised when therapeutics designed to vacuum it up deliver mixed results; this study offers a far more unsettling and, frankly, more interesting proposition: that at least some amyloid assembly is not a mistake at all, but a strategy, and one that the brain can deploy with exquisite intent when a “chaperone” protein is present to keep the process on a tight leash. The implication is not that amyloid is suddenly “good” – biology rarely does moral binaries – but that the difference between memory that evaporates and memory that persists may hinge on whether protein aggregation is regulated rather than merely resisted, which in turn reframes proteostasis as something closer to active governance than passive housekeeping.

For geroscience, the provocation is clear: if cognitive healthspan depends not only on clearing damage but on preserving the machinery that uses potentially dangerous molecular states for constructive purposes, then aging may be less about the arrival of pathology than the slow collapse of control systems – and the next generation of neuroprotective interventions may need to restore the conductor, not just silence the orchestra.

A regulator hiding in plain sight

At the heart of the paper is a J-domain protein the team calls Funes – a “helper” or chaperone protein that shapes how a memory-related protein, Orb2, assembles into an amyloid state [1]. Orb2 is not a newcomer to this story. In earlier work, Si’s lab showed that Orb2 forms amyloid-like oligomers in vivo and that this transformation is required for long-term memory persistence [2].

The missing piece was control. “The fact that amyloid is needed to form memory implied there must be a mechanism that controls the process,” said former Stowers Postdoctoral Research Associate Rubén Hervas, PhD, co-corresponding author on the current study.

The authors describe Funes as a molecular manager with unusually specific taste. In their experiments, the protein interacted with oligomeric Orb2 and, crucially, promoted its conversion into a stable amyloid state linked to memory. In other words, it did not merely stop aggregation; it participated in directing a particular kind of assembly at a particular time [1].

“I wanted to understand how unstable proteins help create stable memories,” Si added. “And now, we have definitive evidence that there are processes within the nervous system that can take a protein and make it form an amyloid at a very specific time, in a specific place, and in response to a specific experience.”

Fruit flies, hungry and highly motivated

The paper leans heavily on a behavioral readout, which is refreshing – a molecular story about memory should, ideally, end with an organism doing something differently. The team used fruit flies trained to associate a specific odor with a sugar reward, and then asked what happened to that learned preference when Funes was disrupted [1].

“We trained very hungry fruit flies to link a specific, unpleasant smell with a sugar reward,” Patton said.

When the authors reduced Funes function, the flies struggled with long-term memory. Restoring the protein improved outcomes, consistent with the idea that Funes is not ornamental biology but part of the machinery that locks experience into persistence. Mechanistically, the paper reports that the J-domain of Funes is required, and that its activity appears to center on guiding Orb2’s “physiological amyloidogenesis” rather than suppressing it outright [1].

There is also a neat literary nod. “We were inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ short story Funes the Memorious … perfect memory comes at a cost, so we named the chaperone Funes,” Kyle Patton, PhD, a former Stowers Graduate School student and lead author on the study said. A bit of wit, yes, but also a reminder that memory is not simply a filing cabinet; it is a metabolic and cognitive trade-off.

Structure matters – especially for translation

If amyloid is to be treated as a tool rather than a toxin, structure becomes the difference between elegance and catastrophe. The authors used cryo-electron microscopy to resolve the architecture of Orb2 amyloid fibrils, reporting a structure “consistent with an endogenous amyloid.” This is not mere molecular stamp-collecting; it is the kind of detail needed if anyone hopes to design interventions that influence assembly without triggering unpredictable aggregation elsewhere.

Generally treated as villains, amyloids are typically associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s. They form tightly packed, highly stable detrimental protein fibrils, but the same protein chemistry, under regulation, can be recruited in the service of long-term memory.

One can feel the therapeutic itch in the language. “It may be possible to either activate these chaperones and guide toxic amyloids to be less harmful – or, by activating them, we can potentially endow the brain with enhanced capacity to form functional amyloids,” Si said. The sentence is speculative but revealing; the target is not necessarily amyloid itself, but the system that tells it when to behave.

Chaperones as cognitive infrastructure

Longevity research has become deeply familiar with the concept of proteostasis – the careful choreography of protein folding, trafficking and clearance that keeps cells functional over time. Chaperones are the stagehands, quietly preventing chaos. This paper proposes something more active: chaperones not only prevent ruin, they may enable precision.

“Ultimately, chaperones may allow the brain to perceive, process, or store information about the outside world,” Si said. It is a bold framing, and it lands in a useful place for the healthspan field. Cognitive aging is not simply the slow accumulation of plaques and tangles; it is also the erosion of resilience, adaptability and signal fidelity – the ability to make meaning, not just to avoid damage.

The authors also gesture toward neuropsychiatric relevance. “If you look at the human version of these genes, they have surprisingly been implicated by genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia,” Patton said. “That’s not something we anticipated.”

From the paper’s perspective, this is an invitation rather than a conclusion: genetic association is not mechanism, and fruit flies are not humans. Still, the direction of travel is intriguing – a protein quality-control axis that sits uncomfortably close to perception and interpretation.

“And in diseases where we do not see the world as it is, like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, we could imagine chaperones playing a role,” Si added.

Aging, regulation and the cost of control

The longevity angle here is not that this work is a ready-made therapy for dementia; it is that the biology of memory may depend on precisely the kind of regulation that aging tends to corrode. Chaperone capacity declines with age across tissues, while misfolded proteins and aggregation-prone states become more common. If Funes-like mechanisms exist in vertebrates – and the team is already hunting for “early evidence” – the implication is that cognitive decline could be driven not only by the appearance of pathological amyloid, but by the weakening of systems that constrain and direct assembly.

“We are now getting early evidence that, like the fruit fly shows in this study, this process may also be manifesting in the vertebrate nervous system,” Si said.

“Our hypothesis is carrying us all the way to the vertebrate brain, illustrating that it may actually be universal,” he added.

That universality is the real wager. Functional amyloid has always been a slightly uncomfortable concept in a world trained to fear plaques, but biology is rarely polite enough to honour our categories. When the same class of structure can encode memory in one context and destroy neurons in another, the story is no longer about good proteins and bad proteins; it is about governance.

Where the real leverage may lie

As the longevity biotech ecosystem matures, it is becoming clearer that prevention is not only about removing damage but about maintaining regulation – the cellular and systems-level ability to keep complicated machinery within safe bounds. In that light, chaperones begin to look less like maintenance staff and more like infrastructure.

“While it’s an unknown universe, it’s an exciting one, and we’ll see where we end up,” Si said.

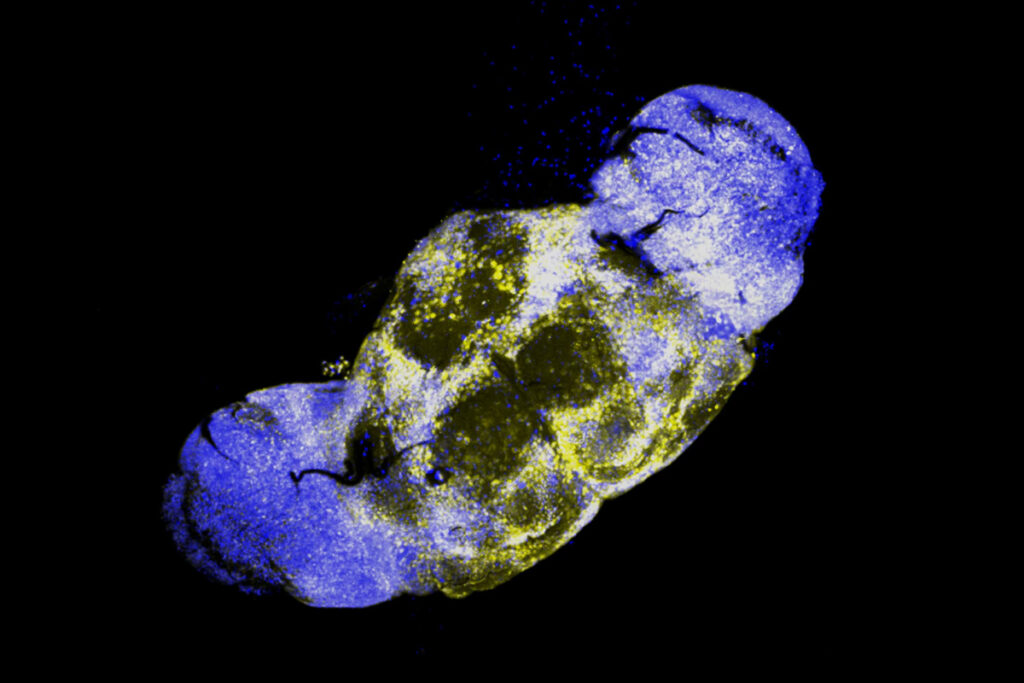

Images courtesy of Stowers Institute for Medical Research. Main image shows a projection of Fly 1b Funes 1

[1] Patton, K, Yi, Y, Burt, R, Ng, K K-S, Mukhi, M, Khaki, P S S, Hervas, R and Si, K (2026) ‘A J-domain protein enhances memory by promoting physiological amyloid formation in Drosophila’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 26 January

[2] https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aba3526