If you zoomed in far enough on a new experimental HIV vaccine, you wouldn’t see the usual protein shell that most vaccines rely on. Instead, you’d find tiny geometric structures folded from strands of DNA—molecular origami designed not to be noticed at all. This “invisible” scaffold may be the key to awakening some of the rarest and most sought‑after cells in immunology: the B cells capable of maturing into broadly neutralizing antibody producers.

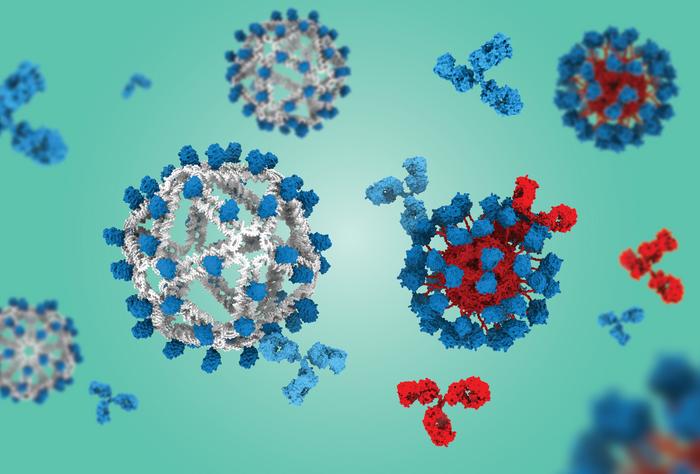

Many next‑generation vaccines use virus‑like particles (VLPs)—nanostructures that mimic the outer shape of a virus but contain no genetic material. By displaying many copies of a viral antigen on their surface, VLPs can activate B cells far more effectively than free‑floating proteins. The paper is titled “DNA origami vaccines program antigen-focused germinal centers,” and was published recently in Science.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies, or bnAbs, are a long‑standing goal of HIV vaccine research because they can disable many strains of the virus at once. HIV mutates so quickly that most antibodies recognize only a single strain, which is why researchers have long sought broadly neutralizing antibodies that target conserved regions of the virus. But bnAbs target deeply conserved regions of the virus—sites HIV can’t easily change without compromising itself. The challenge is that the B cells capable of evolving into bnAb‑producing cells are extraordinarily rare, and they’re easily drowned out by other immune responses.

That’s where the new DNA‑based vaccine platform comes in. Developed by researchers at MIT and Scripps Research Institute, the vaccine uses DNA instead of a protein-based VLP scaffold to display an engineered HIV antigen called eOD‑GT8. This antigen is specifically designed to activate the precursor B cells that can eventually mature into bnAb‑producing lineages. By removing the protein scaffold, the team eliminated a major source of “off‑target” immune responses that can distract the immune system.

“We were all surprised that this already outstanding VLP from Scripps was significantly outperformed by the DNA‑based VLP,” said Mark Bathe, PhD, professor of biological engineering at MIT. “These early preclinical results suggest a potential breakthrough as an entirely new, first‑in‑class VLP that could transform the way we think about active immunotherapies, and vaccine design, across a variety of indications.”

In mouse models engineered with human antibody genes, the DNA‑based vaccine generated dramatically more of the desired precursor B cells than the protein‑based version—about eightfold more in one set of experiments. It also produced a far more focused immune response: nearly 60% of germinal center B cells targeted the HIV antigen, compared to only about 20% with the protein scaffold.

“The DNA‑VLP allowed us for the first time to assess whether B cells targeting the VLP itself limit the development of ‘on‑target’ B cell responses—a longstanding question in vaccine immunology,” said Darrell Irvine, PhD, professor at Scripps Research and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

The key advantage is that B cells don’t mount antibody responses against DNA, which means the scaffold remains immunologically silent. That silence gives the rare bnAb‑precursor cells a better chance to survive, expand, and evolve. “Reducing the competition among other irrelevant B cells may help these rare cells have a better chance to survive,” noted lead author Anna Romanov, PhD.

The implications extend beyond HIV. The same strategy could help focus immune responses for universal influenza vaccines, pan‑coronavirus vaccines, or even active immunotherapies targeting Alzheimer’s‑related proteins or addictive substances.

For now, the DNA‑origami platform offers something HIV vaccine researchers have been chasing for decades: a way to reliably prime the right B cells at the very start of the bnAb pathway. And that first step may finally open the door to a protective HIV vaccine.