A meta analysis of clinical trials data by researchers from the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration has shown that statins do not cause most of the side effects listed in medicine package leaflets. Drawing on individual participant data from more than 150,000 people from 23 double-blind studies, the team found no evidence that statin therapy causes many commonly reported problems such as memory loss, depression, sleep disturbance, erectile dysfunction, fatigue, or headache. The findings, published in The Lancet, are intended to better inform clinicians and patients in making decisions about statin use to manage cardiovascular disease risk.

“Statins are life-saving drugs used by hundreds of millions of people over the past 30 years,” said lead author Christina Reith, PhD, an associate professor at Oxford Population Health. “However, concerns about the safety of statins have deterred many people who are at risk of severe disability or death from a heart attack or stroke. Our study provides reassurance that, for most people, the risk of side effects is greatly outweighed by the benefits of statins.”

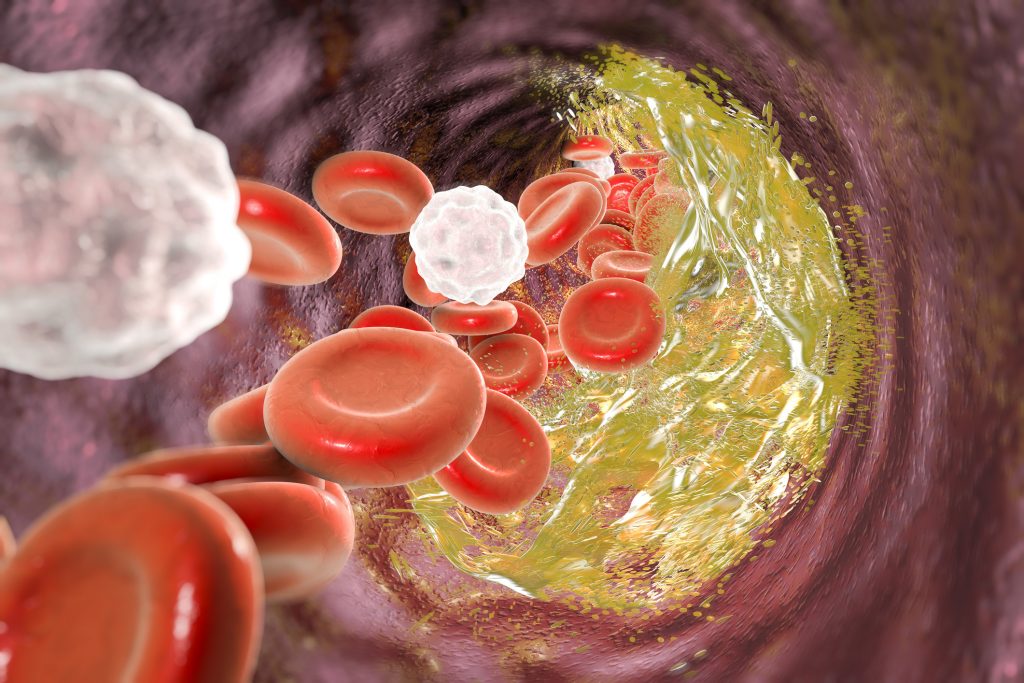

Statins lower LDL cholesterol and reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes, but uncertainty about side effects has affected uptake and persistence with treatment. The CTT Collaboration is an international research collaboration formed in 1994 in recognition of the fact that no single randomized clinical trial of lipid-lowering drug candidates would have enough participants to provide reliable assessments of mortality outcomes. To address this, CTT researchers conducts individual patient data meta analyses of long-term studies with more than 1,000 patients. To date, the collaboration’s work has focused on statins and now has data from 28 major statin trials comprising more than 175,00 trial participants.

For this new analysis the researchers used data from 19 trials comparing statins with placebo, involving 123,940 participants, and four trials that compared more intensive with less intensive statin therapy, involving 30,724 participants. All trials were double-blind and followed the patients for a median of nearly five years. The list of potential side effects was compiled from product information for five commonly prescribed statins.

“Statin product labels (e.g., Summaries of Product Characteristics [SmPCs]) list certain adverse outcomes as potential treatment-related effects based mainly on non-randomized and non-blinded studies, which might be subject to bias,” the researchers wrote. The CCT method that uses individual participant-level data allows the team to compare rates of adverse events within each trial between randomly assigned groups.

Of the 66 outcomes assessed beyond muscle symptoms and diabetes, only four showed a statistically significant association with statin therapy and included abnormal liver transaminases, other liver function test abnormalities, urinary composition alteration, and edema. The absolute excess risk for combined liver test abnormalities was about 0.13% per year. There was no increase in clinical liver disease such as hepatitis or liver failure.

For cognitive outcomes, rates were identical between groups. Reports of memory impairment occurred in 0.2% per year among people taking statins and 0.2% per year among those taking placebo. Similar patterns were seen for depression, sleep disturbance, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, nausea, fatigue, and headache.

These findings contrast with information in package leaflets, which often list a wide range of possible side effects. Senior author Sir Rory Collins, FRS, FMedSci, a professor of medicine in the clinical trial service unit at Oxford University said: “Statin product labels list certain adverse health outcomes as potential treatment-related effects based mainly on information from non-randomized studies which may be subject to bias. We brought together all of the information from large, randomized trials to assess the evidence reliably.”

Earlier work by the CTT has shown that most muscle symptoms reported by patients taking statins are not caused by the drugs, with only about one percent experiencing statin-related muscle symptoms in the first year of treatment. The analysis also showed that statins can lead to a small increase in blood sugar levels, leading to diabetes diagnosis in some people already at high risk. It was these findings prompted the current broader examination of other potential side effects.

While it’s important to better inform doctors of the true risks of statin use, this newest study can also help alleviate patient concerns. “Widespread confusion about statin safety hinders the ability of doctors and patients to make informed decisions about initiating or continuing statin therapy,” the researchers wrote. Previous analyses linked negative media coverage of statins to increases in treatment discontinuation and potentially avoidable cardiovascular events.

For clinicians, the results offer clearer guidance when discussing risks and benefits with patients. Bryan Williams, MD, chief scientific officer of the British Heart Foundation said the evidence “should help prevent unnecessary deaths from cardiovascular disease” and support decisions about when alternative treatments may be needed.

The team noted that the liver enzyme changes it uncovered appear to be tied to dosing levels and that these changes typically do not lead to serious disease. Work on these data is ongoing to examine biochemical liver function data in more detail and to assess additional adverse events noted in the trials that were not included in the current analysis.