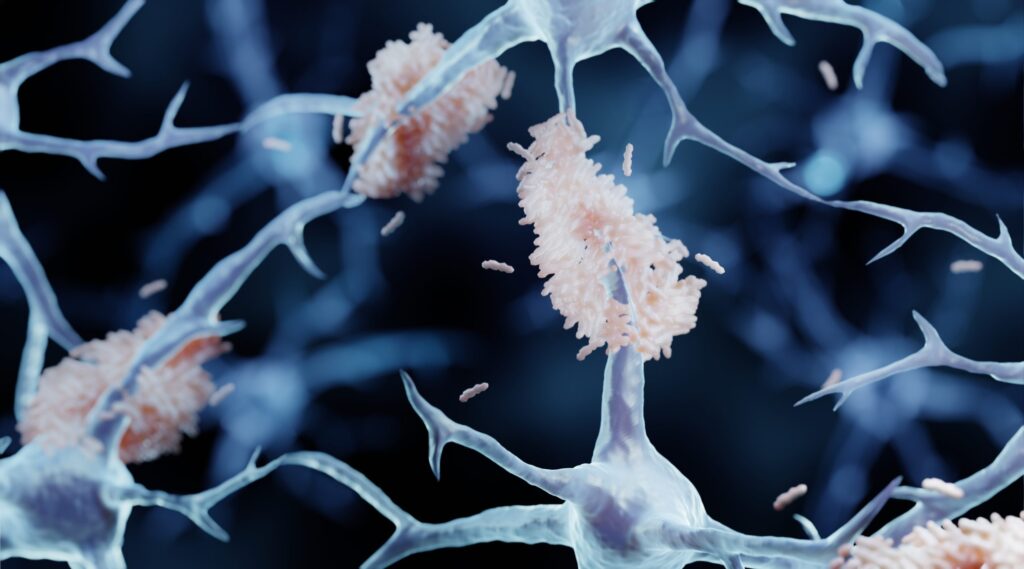

Scientists have long known Alzheimer’s disease (AD) involves the build up of toxic amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the brain but have struggled to understand how these harmful protein fragments are produced. An international research team headed by scientists at Northwestern University has now pinpointed when and where toxic proteins accumulate within the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients, and discovered that a decades-old FDA-approved anti-epileptic drug can stop the accumulation process before it even begins.

Studying animal models, human neurons and brain tissue from high-risk patients, the team found that a particularly toxic protein fragment, amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42), accumulates inside neurons’ synaptic vesicles (SVs), the tiny packets that neurons use to send signals. They discovered that how amyloid precursor proteins (APP) is trafficked also controls whether a neuron forms amyloid-beta 42. Their experiments also showed that administering to animals and to human neurons the inexpensive anti‑seizure drug levetiracetam (Lev), prevented neurons from forming amyloid-beta 42.

“While many of the Alzheimer’s drugs currently on the market, such as lecanemab and donanemab, are approved to clear existing amyloid plaques, we’ve identified this mechanism that prevents the production of the amyloid‑beta 42 peptides and amyloid plaques,” said Jeffrey Savas, PhD, associate professor of behavioral neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “Our new results uncovered new biology while also opening doors for new drug targets.”

Savas is corresponding author of the team’s published paper in Science Translational Medicine, titled “Levetiracetam prevents Aβ production through SV2a-dependent modulation of APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease models,” in which they concluded “Together, our findings document impaired presynaptic protein degradation early in amyloid pathology and reveal the therapeutic mechanism of action for Lev to prevent the production of Aβ and, consequently, downstream irreversible damage.”

Savas said, “In our 30s, 40s and 50s, our brains are generally able to steer proteins away from harmful pathways. As we age, that protective ability gradually weakens. This is not a statement of disease; this is just a part of aging. But in brains developing Alzheimer’s, too many neurons go astray, and that’s when you get amyloid-beta 42 production. And then it’s tau (or ‘tangles’), and then it’s dead cells, then dementia, then neuroinflammation—and then it’s too late.”

Central to the researchers’ newly reported discoveries is APP, a protein that plays important roles in brain development and synaptic formation. Abnormal processing of APP can lead to the production of amyloid‑beta peptides, which play a central role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. “Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides are a defining feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD),” the authors wrote. “These peptides are produced by the proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), which can occur through the synaptic vesicle (SV) cycle.” However, they noted, how amyloidogenic APP processing impacts on SV composition and presynaptic function isn’t well understood.

Levetiracetam (Lev) is an atypical antiepileptic drug (AED) that, during the synaptic vesicle cycle—a fundamental process that underlies every thought, movement, memory or sensation—binds to a protein called SV glycoprotein 2A (SV2A). “Lev has emerged as a potential therapeutic for AD because it mitigates excess synaptic activity and because Aβ can be produced and released through the SV cycle,” the investigators continued. “In AD animal models and patients with AD, Lev treatment reduces plaque pathology and memory deficits and slows cognitive decline.” Levetiracetam is also the subject of several clinical trials for AD, the researchers noted, “… but the mechanisms by which it helps reduce AD pathology are still unclear.”

The team mined existing human clinical data to investigate whether Alzheimer’s disease patients who took levetiracetam experienced slowed cognitive decline. They obtained clinical data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center and conducted a correlative analysis, finding that Alzheimer’s patients who took levetiracetam were associated with a significant delay from the diagnosis of cognitive decline to death compared to those taking lorazepam or no/other anti-epileptic drugs. “Although the magnitude of change was small (on the scale of a few years), this analysis supports the positive effect of levetiracetam to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s pathology,” Savas said.

Findings from the studies carried out by Savas and colleagues indicate that the interaction between levetiracetam and SV2A interaction slows down a step in which neurons recycle synaptic vesicle components from the cell’s surface. By pausing this recycling process the drug enables APP to remain on the cell’s surface longer, diverting it away from the pathway that produces toxic amyloid‑beta 42 proteins. “In this study, we found that Lev reduces amyloidogenic APP processing by decreasing SV cycling, which results in increased APP cell surface expression,” the authors stated. “We found that SV2a is required for Lev to prevent Aβ42 production and correct SV protein levels.”

![Corresponding study author Jeffrey Savas points at a computer as he and his lab members discuss their recent paper in Science Translational Medicine. [Northwestern University]](https://www.genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/low-res-1-1-300x225.jpeg)

To effectively prevent Alzheimer’s symptoms, high-risk individuals would need to begin taking levetiracetam “very, very early,” Savas said, possibly up to 20 years before the new FDA-approved Alzheimer’s disease test would even capture mildly elevated levels of amyloid-beta 42. “You couldn’t take this when you already have dementia because the brain has already undergone a number of irreversible changes and a lot of cell death,” Savas said.

Because of this, Savas said he and his team might attempt to identify patient populations with genetic forms of Alzheimer’s, which includes patients with Down syndrome. Although these patients are somewhat rare, they are the key group to benefit from these discoveries.

In addition to using genetically engineered mouse models and cultured human neurons, the scientists studied human brain tissue from deceased patients with Down syndrome who died in their 20s or 30s from car accidents or other events. More than 95% of patients with Down syndrome will develop an early and aggressive form of Alzheimer’s by around age 40 years, Savas noted, because the APP gene is linked to the chromosome that is triplicated in their genome. “By obtaining Down syndrome patient brains from people who died in their 20s or 30s, we know they would have eventually developed Alzheimer’s, so it gives us an opportunity to study the very initial early changes in the human brain,” Savas said.

The study found these brains had the same accumulation of presynaptic proteins that Savas’ lab had found in engineered mouse models in a previous paper. “That is what we and others call the paradoxical stage of Alzheimer’s disease, which is that before synapses are lost and dementia ensues, the first thing that happens is presynaptic proteins accumulate,” Savas commented. “So conceivably, if you started giving these patients levetiracetam in their teenage years, it could actually have a preventative therapeutic benefit.” In their paper the authors wrote, “… because individuals with DS exhibit elevated amyloid production and similar presynaptic perturbations our findings suggest that Lev could be leveraged to delay the onset of amyloid pathology in this population.”

Savas acknowledged that levetiracetam “is not perfect,” and noted that the drug breaks down in the body very quickly. He and others are in the process of making a better version of levetiracetam, which would last longer in the body and help better target the mechanism that prevents the production of the plaques.

In their paper the team concluded, “Together, our findings document impaired presynaptic protein degradation early in amyloid pathology and reveal the therapeutic mechanism of action for Lev to prevent the production of Aβ and, consequently, downstream irreversible damage.”