Biologists often say that structure determines function. In a new study, Northwestern University researchers show that this principle applies not only to proteins but may also to cancer vaccines—where the nanoscale arrangement of a single peptide can dramatically alter therapeutic potency. By re‑engineering the orientation of an HPV‑derived antigen on a spherical nucleic acid (SNA) platform, the team created a vaccine that slowed tumor growth and extended survival in preclinical models of HPV‑driven cancer.

The work, published in Science Advances and titled “E711‑19 Placement and Orientation Dictate CD8⁺ T Cell Response in Structurally Defined Spherical Nucleic Acid Vaccines,” explores how subtle architectural changes can reshape immune activation. HPV‑positive head and neck cancers, which are rising in incidence, often present at advanced stages and are treated with toxic regimens, according to the authors. While prophylactic HPV vaccines prevent infection, they do not help patients with established tumors—leaving a need for therapeutic strategies that can safely drive strong cytotoxic T‑cell responses.

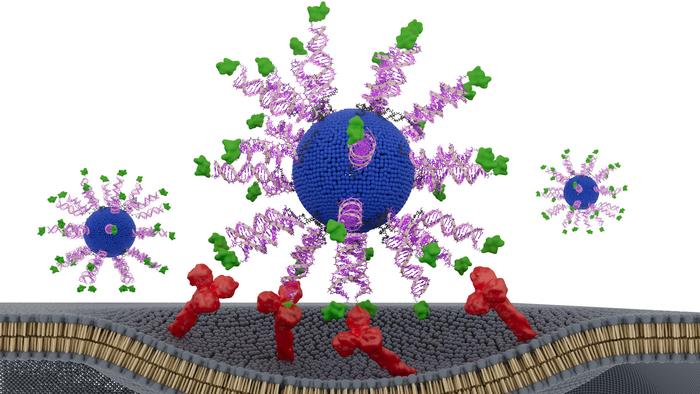

To address this, the researchers designed three SNA‑based vaccines containing identical components: a lipid core, CpG adjuvant, and a short HPV16 E711‑19 peptide. The only difference was how the antigen was displayed. One formulation buried the peptide inside the nanoparticle, while two others attached it to the surface through either the N‑terminus or C‑terminus—a small structural shift with potentially large immunological consequences.

The differences were striking. All three SNAs enhanced dendritic cell activation and CD8⁺ T‑cell cytotoxicity compared to a simple peptide‑adjuvant mixture, but the N‑terminally displayed version, dubbed N‑HSNA, consistently outperformed the others. It induced roughly eight‑fold higher interferon‑γ secretion and about 2.5‑fold greater cytotoxicity in primary human cells, the authors wrote.

In tumor‑bearing AAD mice, the N‑HSNA formulation cut tumor burden by more than threefold and extended survival, while also driving a noticeable expansion of CD8⁺ T cells. The same design performed strongly in patient‑derived HPV‑positive head and neck cancer spheroids, where it produced roughly a 2.5‑fold increase in tumor‑cell killing—a sign that the structural tuning may translate across model systems.

The findings highlight the emerging field of “structural nanomedicine,” which emphasizes the deliberate arrangement of vaccine components rather than simply mixing them together—what lead author Chad A. Mirkin, PhD, calls the “blender approach.”

“There are thousands of variables in the large, complex medicines that define vaccines,” said Mirkin, the George B. Rathmann Professor at Northwestern. “The promise of structural nanomedicine is being able to identify the configurations that lead to the greatest efficacy and least toxicity. In other words, we can build better medicines from the bottom up.”

By demonstrating that antigen placement and orientation can dictate immune potency, the study provides a blueprint for revisiting past cancer vaccines that failed not because of their ingredients, but perhaps because of their architecture. The authors suggest that rational design—potentially aided by machine learning—could accelerate the development of more effective therapeutic vaccines for HPV‑driven tumors and beyond.