University of Virginia (UVA) Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers have developed a small-molecule compound that targets advillin, or AVIL, an oncogene that drives the growth and survival of glioblastoma (GBM) cells. In a report published in Science Translational Medicine, the UVA team showed that inhibiting AVIL curbed tumor growth in cell models and in mouse models by blocking the gene’s activity without evidence of harmful side effects, providing a new avenue to potentially treat a form of cancer that has limited treatment options.

“Glioblastoma is a devastating disease. Essentially no effective therapy exists,” said senior author Hui Li, PhD, a professor of pathology at the UVA School of Medicine. “What’s novel here is that we’re targeting a protein that GBM cells uniquely depend on, and we can do it with a small molecule that has clear in vivo activity. To our knowledge, this pathway hasn’t been therapeutically exploited before.”

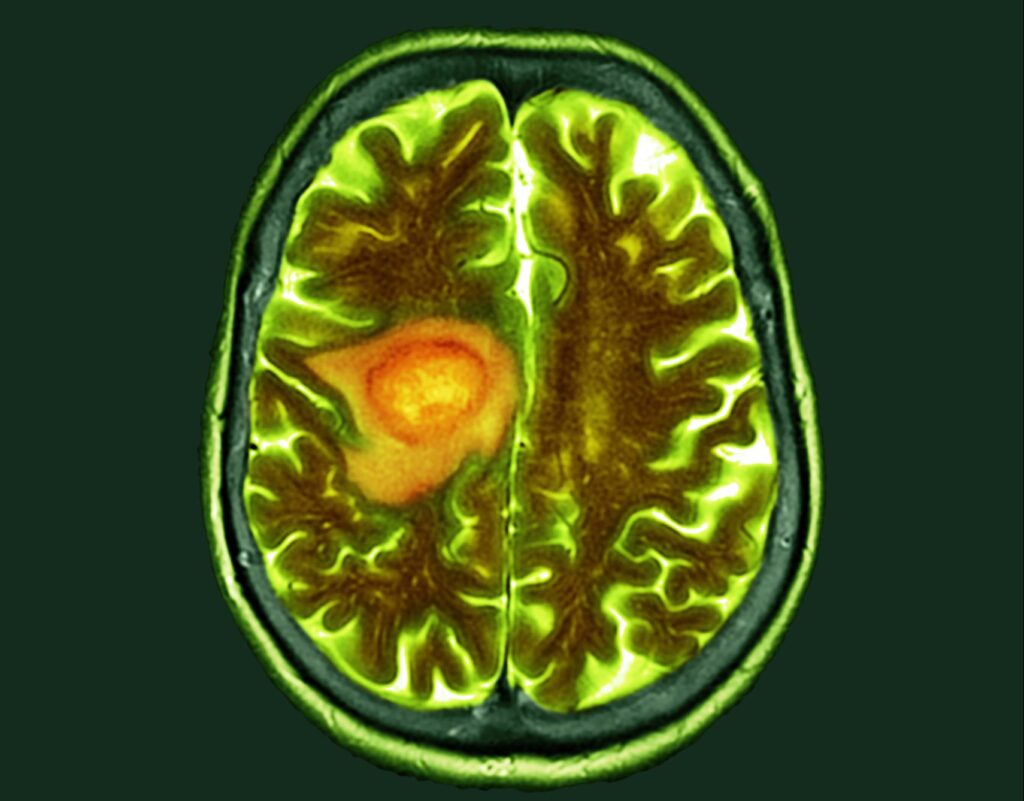

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest brain cancer, with about 14,000 new diagnoses each year in the U.S. Survival after diagnosis is typically about 15 months, and standard treatments such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy extend life only modestly. Temozolomide, the most widely used drug, adds an average of just a few months of survival and can carry substantial side effects.

Li’s research group first identified AVIL as an oncogene in glioblastoma in 2020. In that study, the researchers showed that silencing AVIL could destroy glioblastoma cells in laboratory models and halt tumor growth in mice, without affecting healthy brain cells. However, that approach, which used RNAi, is not practical for translating to a potential therapeutic for human use, which spurred the UVA team’s search for another method.

The new study examined AVIL expression across glioblastoma samples and confirmed that it is highly expressed across all molecular subtypes and cellular states, including glioblastoma stem cells and tumors resistant to temozolomide. This compares with healthy brain tissue which shows little, if any, expression of AVIL.

Several features made AVIL an appealing therapeutic target. “As a target, AVIL has several attractive features,” Li said, referencing their published research. The first is that AVIL is highly expressed in GBM compared with healthy brain tissue. While their 2020 paper found that AVIL expression is enriched in a large portion of GBMs, the new study shows that this is the case for all four molecular subtypes of glioblastoma and four single cell states. Also notable is AVIL is even more highly expressed in glioblastoma stem cells and high expression was retained in samples resistant to temozolomide (TMZ) the most prescribed oral chemotherapy for GBM.

“Our previous study has shown that AVIL alone is sufficient to transform immortalized astrocytes, and it seems to be a merging point for three main signaling pathways in GBM,” the researchers wrote. “Silencing AVIL is sufficient to kill GBM cells and prevent in vivo xenograft formation. Finally, targeting AVIL appears safe. We previously observed no effect of AVIL silencing on normal astrocytes or on neural stem cells.”

To identify a compound capable of inhibiting AVIL, the team turn to high-throughput screening to evaluate large numbers of small molecules for their ability to interfere with AVIL activity. This led them to what they term Compound A, which binds directly to the AVIL protein and blocks its interaction with actin. Encouragingly, Compound A was shown to induce changes similar to those seen when AVIL was silenced wit RNAi in the previous study. Treatment suppressed FOXM1 and LIN28B, two downstream targets involved in cell proliferation and cancer progression, and produced whole-transcriptome changes consistent with AVIL inhibition. Tumor cells with higher AVIL expression were more sensitive to the compound, while astrocytes and neural stem cells were largely spared

In animal studies, an oral formulation of Compound A showed it was capable of crossing the blood-brain. In all, the team tested the compound in five different mouse models of glioblastoma, including intracranial tumors and patient-derived xenografts that were sensitive or resistant to temozolomide. Tumor growth was reduced and even at higher doses, there was no evidence of treatment toxicity.

While Compound A is not a novel compound, “it has not been tested in humans,” Li said. With their eye clearly on moving it into Phase I clinical studies withing the next two years, Li’s lab is now focused on optimization.

“We have developed more than 160 derivatives of compound A, some of lead compounds with nanomolar IC50s,” Li said. “We are optimizing the lead compounds to improve drug-like properties.”

In the lab’s research, the team compared AVIL to another oncogene, ALK, which is known to be active in a variety of malignancies. When asked if AVIL might have similar effects as a potential treatment for other cancers, Li said, “Yes, [it is] mostly unpublished data, but we have results supporting AVIL’s critical role in pediatric sarcoma and some common solid cancer.”

As such, AVIL is a promising potential strategy for GMB as it focuses on a tumor-specific dependency compared with the current cytotoxic approaches of radiation and chemotherapy a potent breakthrough considering standard therapy “hasn’t fundamentally changed in decades, and survival remains dismal,” the researchers wrote.