Spatial proteomics maps early molecular changes in subchondral bone, offering potential biomarkers and reframing osteoarthritis as a whole-joint disease.

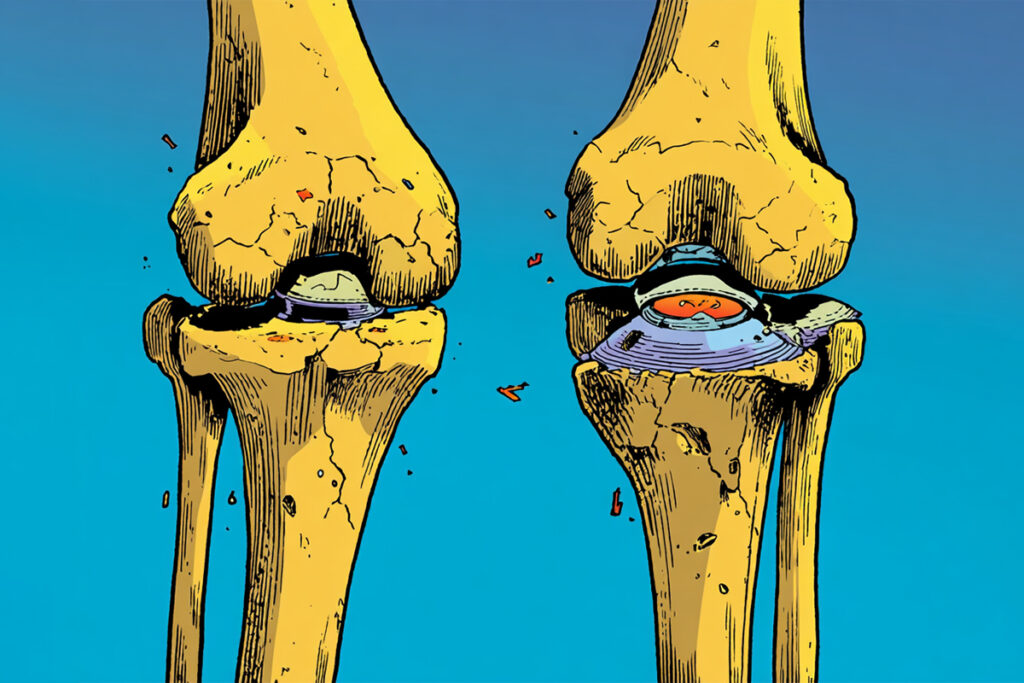

We have typically defined osteoarthritis by its end-stage symptoms – the telltale narrowing of joint gaps on an X-ray or the structural collapse of cartilage seen on an MRI – rather than the molecular shifts that precede them. Now a new study led by researchers at the Buck Institute suggests the biology may have been active long before those images turn ominous. By applying spatial proteomics to samples from knee replacements, the team built a molecular atlas that caught the disease in the act; they found ‘damaged bone signatures’ lurking beneath surface cartilage that hadn’t even begun to thin yet [1].

This research, published in Bone Research, bypasses the usual limitations of proteomics by pairing high-resolution mass spectrometry imaging with targeted enzymes to digest proteins right where they sit in the tissue. It’s a messy, technically grueling process – mostly because mineralized bone is notoriously difficult to analyze – but the payoff is a layered molecular atlas. For the first time, we can see the exact coordinates of collagen remodeling and protein shifts as they happen across the joint.

A molecular map of joint degeneration

By analyzing osteochondral samples from patients undergoing knee replacement surgery, the researchers identified differential protein patterns between damaged cartilage, relatively preserved cartilage and underlying subchondral bone. Notably, bone beneath cartilage that appeared macroscopically intact still exhibited a distinct molecular signature [1].

As the authors write, the data reveal “region-specific alterations in extracellular matrix composition” and suggest that subchondral bone remodeling may be more tightly intertwined with cartilage degeneration than previously appreciated. Collagen fragments and modified matrix proteins – including hydroxyproline-containing peptides consistent with active remodeling – were spatially localized, providing biochemical context to structural change.

Such findings lend weight to the view of osteoarthritis as a whole-joint disease, involving bone, cartilage and synovium in dynamic interplay rather than a unidirectional process of cartilage erosion. In practical terms, that reframing could matter for when and how intervention begins.

Longevity.Technology: Osteoarthritis has long been filed under “wear and tear” – a phrase that feels reassuring right up until you realize it quietly absolves us of doing anything clever about it; this study is a useful irritant to that complacency, because its molecular maps suggest the subchondral bone is not merely the silent victim of cartilage failure but an early, biochemically noisy participant, broadcasting a damage signature even beneath cartilage that still looks respectable on histology. That matters for longevity not because knees are glamorous, but because mobility is compounding interest for healthspan – once joint pain sidelines people, everything else (cardiometabolic health, muscle mass, social participation, independence) tends to follow it down the stairs. The prospect of ECM and collagen remodeling markers showing up not only in tissue but in synovial fluid hints at a future in which OA is staged and tracked by biology rather than belated radiology – which is exactly what disease-modifying trials have been missing – but we should keep our excitement on a leash: the cohort is small, the samples are largely end-stage and the leap from a beautifully resolved MALDI image to a robust, scalable diagnostic is a long one. Still, if geroscience is serious about prevention, it could do worse than start with the conditions that quietly steal movement years before they steal life – and OA has been doing that in plain sight for decades.

From tissue to biomarker

One of the more translationally relevant observations is that several extracellular matrix components identified in tissue were also detectable in synovial fluid. While synovial aspiration is not a screening tool for primary care, it is routinely performed in orthopedic settings and clinical trials; molecular markers that correlate with disease stage or progression could therefore become practical tools for patient stratification.

“This study gives us a much clearer picture of what osteoarthritis looks like at the molecular level,” said senior author Dr Birgit Schilling professor at the Buck Institute. “By understanding how joint tissues change with aging and disease, we can begin to identify earlier warning signs and develop better ways to slow or prevent joint damage.”

The emphasis on earlier warning signs is not incidental. Osteoarthritis remains largely managed with analgesia, physical therapy and, eventually, joint replacement. Disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs have proved elusive, in part because intervention often begins after structural damage is well established. A biologically informed staging system – one grounded in proteomic shifts rather than radiographic end points – could sharpen clinical trials and clarify therapeutic windows.

Technical advances in a difficult tissue

Analyzing mineralized, matrix-dense tissue is an analytical nightmare; it’s usually too ‘thick’ for standard tools to see through. By tailoring enzymatic digestion specifically for the extracellular matrix, the team managed to pull clear signals from collagen-derived peptides and modifications that usually stay hidden in the noise [1]. This isn’t just a technical win for the lab; it essentially hands us a new lens for looking at musculoskeletal aging, uncovering details that were previously invisible.

But our figurative horses still need holding; the cohort was small and composed of individuals undergoing knee replacement – effectively end-stage disease – and the cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about temporal sequence. Whether the observed bone-associated signatures truly precede cartilage degeneration, or represent parallel processes at advanced stages, will require longitudinal sampling and inclusion of earlier disease.

Movement as infrastructure

When a joint fails, it’s never just about the joint. The loss of mobility kicks off a domino effect that leads straight to muscle loss, metabolic breakdown, and frailty – creating a massive economic and social burden for aging societies. Mapping the molecular shifts in a knee won’t solve those macroeconomic crises overnight, but it gives us the ground truth we’ve been missing for early detection and smarter, more rational treatments.

In that frustrating gap between a clean X-ray and a patient’s first pang of pain lies the biology – intricate, hidden, but finally, measurable. Whether that measurement translates into preventive strategies will depend on replication, validation and careful clinical integration. For now, the map is sharper. The terrain, as ever, is complex.