Researchers at the Sant Pau Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, have developed an MRI-based tool that can more accurately identify progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD), two rare and underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonian disorders. The study, published in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, shows that structural magnetic resonance imaging can be used both to enrich clinical trials with patients who have a high probability of underlying four-repeat tau pathology and to track disease progression with greater sensitivity than functional or symptom severity scales.

“These are diseases that cause balance problems, falls, stiffness, or difficulties with speech and movement. Many patients initially present as if they had Parkinson’s disease or are simply older adults with mobility difficulties,” said first author Jesús García-Castro, a neurologist at Hospital de Sant Pau. “This means they are greatly underdiagnosed, and for years we have not known with enough certainty which disease each patient actually had.”

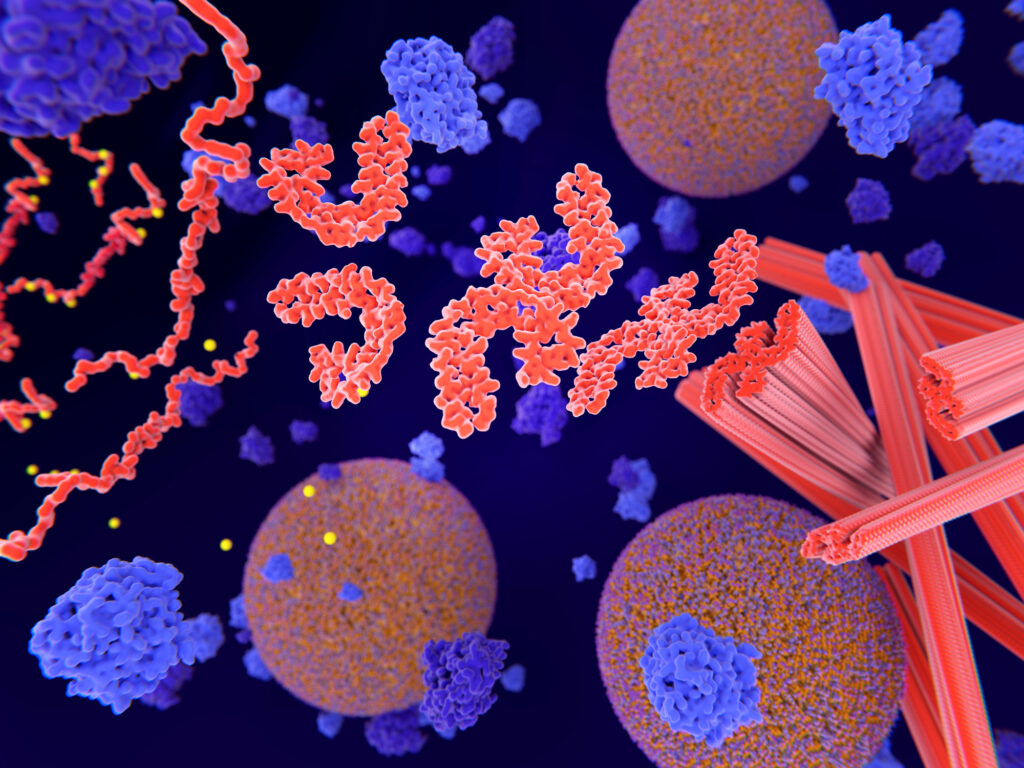

PSP and CBD are classified as primary four-repeat tauopathies, defined by pathological aggregates of tau protein composed predominantly of proteoforms with four microtubule-binding domain repeats. Tau is essential for normal neuronal function, but when it accumulates abnormally, it can cause progressive damage in specific regions of the brain, resulting in impaired movement control, balance, posture, speech, and cognition.

Because PSP and CBD share many of the same symptoms, they have been difficult to diagnose since four-repeat symptoms are often indistinguishable from those caused by other neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. “They resemble Parkinson’s because of their motor symptoms, but they share with Alzheimer’s the fact that they are caused by tau pathology. The problem is that, until now, we did not have reliable tools to distinguish them properly,” said senior author Ignacio Illán-Gala, MD, PhD, a behavioral neurologist and neuroscientist at San Pau Hospital.

To address this diagnostic gap, the Sant Pau team applied and refined an MRI-based logistic regression model that was previously trained on autopsy-confirmed cases of the two diseases. In the current study, the participants were already enrolled in the 4 Repeat Tauopathy Neuroimaging Initiative and from the Phase II/III clinical trial of Davunetide for the treatment of PSP. For this work, the researchers tested whether MRI could both improve clinical trial recruitment while also providing more accurate outcome measures.

The team’s approach sought to develop specific data-driven MRI signatures of PSP and CBD by combining regional brain volumes and cortical thickness measures. They found that in PSP, the disease-specific signature showed it affected deep brain structures, particularly the midbrain and pons, along with selective cortical thinning. In CBD, cortical regions related to motor control and sensory integration were more prominently affected.

“Although they may look very similar clinically, at the brain level, PSP and CBD damage the brain in different ways,” said Illán-Gala. “These differences are reflected on MRI, and by combining them into a signature, we can much better determine which disease each patient has.”

The work by the San Pau researchers showed that MRI-derived models can identify PSP or CBD with high accuracy, and MRI-based signatures can track disease progression more accurately than current approaches.

Perhaps the most powerful application of this new finding may be in the recruitment of patients for PSP and CBD clinical trials by more accurately identifying appropriate patients to enroll. “For a company or an academic consortium to commit to a clinical trial, it has to be feasible,” Illán-Gala noted. “If a trial requires a thousand patients, it is practically impossible. But if it can be conducted with a reasonable number of well-selected individuals and objective measures of progression, then there is a real chance of demonstrating whether a treatment works.”

There remain some hurdles in this approach before it is widely adopted, the researchers noted, including scanner heterogeneity and the need for validation of the signatures in independent patient cohorts. To address this, the San Pau team is developing approaches such as site-specific cutoffs and harmonized imaging protocols that could aid in broader implementation.

“Our goal is to reach a situation similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease, where a combination of a blood test and an MRI scan allows these diseases to be diagnosed at very early stages and with much greater confidence,” García-Castro said. “Improving diagnosis is the first step so that these patients, who currently have no therapeutic options, can begin to have them.”