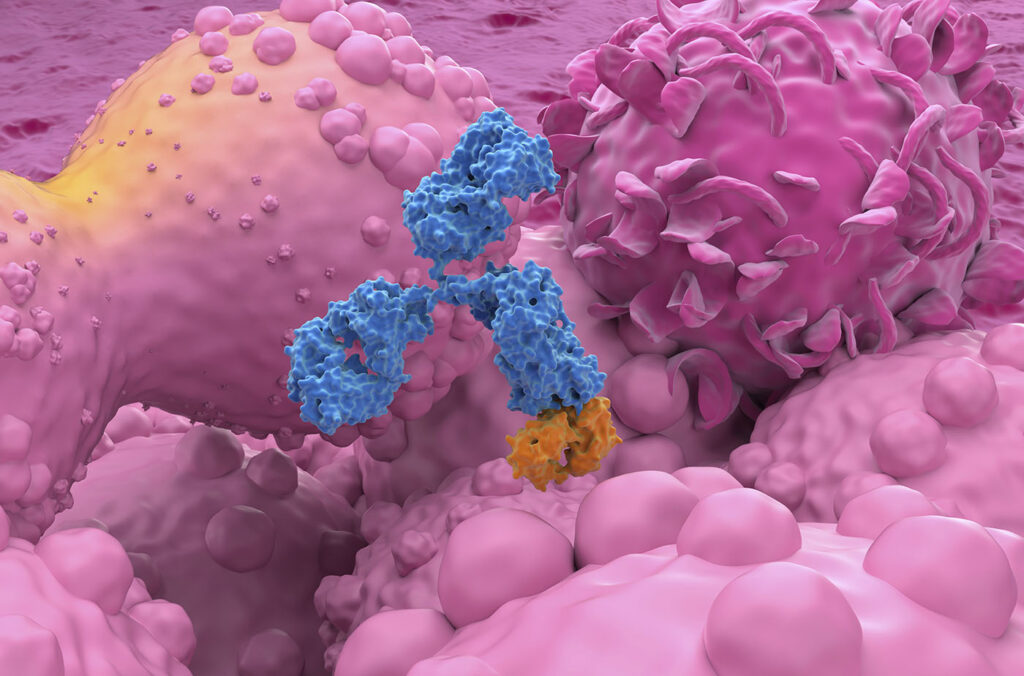

For more than three decades, therapeutic antibodies have occupied a central place in modern medicine. Engineered to bind disease-related targets with extraordinary specificity, monoclonal antibodies and their derivatives have reshaped treatment for cancer, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disorders, and chronic inflammatory conditions. They have transformed once-fatal diagnoses into manageable illnesses and created one of the most commercially successful classes of drugs in pharmaceutical history.

Yet, the antibody revolution has always carried a practical burden. Antibodies are powerful but demanding medicines. They must be manufactured outside the body in large-scale bioreactors, purified through complex downstream processes, transported under strict cold-chain conditions, and delivered to patients repeatedly—sometimes every few weeks, sometimes monthly, and often indefinitely. The burden is logistical, financial, and biological. Many patients must return to clinics for infusions or injections, drug levels fluctuate between doses, and access to treatment can be constrained by geography, adherence, or tolerance.

In many chronic diseases, the limiting factor is no longer whether antibodies work, it is whether patients can reliably receive them at the right concentration, in the right tissue, and for long enough to maintain benefit. This gap between therapeutic potential and practical delivery is especially visible in ophthalmology, neurology, and oncology—fields in which disease biology is well understood, but sustained access to treatment remains challenging.

Gene therapy proposes a fundamental inversion of this paradigm. Instead of repeatedly administering antibodies as finished products, scientists may deliver the genetic instructions that encode them. Viral vectors or lipid-based nanocarriers carry DNA or RNA into target cells, enabling those cells to manufacture therapeutic antibodies—or antibody fragments—directly within the body. In effect, tissues become living bioreactors, capable of producing biologics continuously and locally.

The appeal is obvious: sustained exposure, fewer interventions, reduced treatment burden, and the possibility of reaching tissues that conventional antibody delivery struggles to access. But the shift also introduces new challenges. Continuous in vivo expression challenges assumptions about dosing, reversibility, immune responses, and long-term safety. Antibodies optimized for intermittent exposure must be redesigned for permanent or semi-permanent residence. Delivery vehicles must be retargeted with unprecedented precision. And immune reactions—once manageable through dosing schedules—can threaten durability altogether.

Across industry and academia, several complementary strategies are emerging to meet these challenges. Four examples—spanning large pharmaceutical development, viral delivery innovation, late-stage retinal gene therapy, and antibody-decorated nanocarriers for cancer—illustrate how antibodies are being transformed from injectable drugs into programmable biological functions.

Rethinking antibody design

At Sanofi, Christian Mueller, PhD, vice president and global head of genomic medicine, frames the challenge of antibody gene therapy in three words: delivery, durability, and safety. Each is familiar from gene therapy’s history, but antibodies complicate all three in distinctive ways.

Vice President

Sanofi

“In traditional antibody therapy, dosing is intermittent and adjustable,” Mueller explained. Clinicians can titrate exposure, pause treatment, or discontinue therapy altogether. Gene therapy collapses much of that flexibility. Once a gene is delivered and expressed, the body may produce the antibody continuously for years. “You’re moving from intermittent dosing to continuous in situ production,” he said.

Delivery remains the first hurdle. Achieving therapeutic expression requires not just getting genetic material into the body, but ensuring that it is expressed in the correct tissue and cell types at appropriate levels. “It remains difficult to achieve sufficient expression in the right tissue and cell types—especially beyond immune-privileged sites—while limiting off-target exposure,” Mueller noted. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), the workhorse vectors of gene therapy, have natural tissue preferences that are not always desirable. Many serotypes accumulate in the liver even when the liver is not the intended target, reducing efficiency and increasing safety concerns.

Durability, paradoxically, is both the goal and vulnerability of gene therapy. Sustained expression is essential for long-term benefit, yet immune responses can undermine it. The immune system may recognize the viral vector as foreign, eliminate transduced cells, or generate antibodies against the expressed therapeutic protein itself. “Immune responses to the vector and/or to the expressed antibody can limit sustained expression and complicate redosing,” Mueller explained. Redosing, which is routine for injectable antibodies, is often infeasible for gene therapies, creating a one-shot risk profile.

Safety becomes more complex when exposure is continuous rather than episodic. Injected antibodies are cleared over time; gene-encoded antibodies persist. “Long-term in vivo expression requires careful control of dose, biodistribution, and antibody biology,” Mueller said. Any liability—aggregation, unintended effector function, excessive local concentration—might persist rather than dissipate.

To address these challenges, the field is redesigning antibodies specifically for gene-therapy contexts. Mueller describes advances across the entire “design-to-delivery stack,” including engineered capsids, optimized routes of administration, and tissue-specific regulatory elements that confine expression even if vectors reach unintended sites. Antibodies themselves are being reformatted into gene therapy-ready designs optimized for secretion efficiency, improved stability, extended half-life, and reduced immune liabilities, allowing them to function effectively at lower expression levels.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have become crucial enablers of this redesign. “AI/ML has been incredibly useful because the sequence space is enormous,” Mueller said. Predictive models help prioritize variants with improved solubility, reduced aggregation risk, and lower immunogenicity. Similar tools are now being applied to vector design, tissue targeting, and regulatory-element selection, shortening iteration cycles while retaining experimental validation as the ultimate arbiter.

Antibodies guide delivery

While Sanofi focuses on antibodies as gene-encoded therapeutics, Regeneron is also exploring antibodies as delivery tools. Sven Moller-Tank, PhD, director of viral delivery technologies at Regeneron, sees antibodies as molecular guides capable of steering gene therapy vectors to precise destinations.

Director

Regeneron

“Antibodies can be used for multiple applications in gene therapy due to their specific and high-affinity binding,” Moller-Tank explained. That specificity can be exploited not only to bind disease targets, but to direct delivery vehicles to tissues of interest or modulate immune responses that interfere with the effectiveness of gene therapies.

One persistent challenge is off-target accumulation in the liver. Many AAV vectors localize there by default, even when targeting muscle or brain. This can limit efficacy and raise safety concerns. “By combining antibody targeting with liver-detargeted capsids,” Moller-Tank said, “it may be possible to increase delivery to targets that have historically been hard to reach and reduce unnecessary liver exposure.”

The core innovation is the bispecific antibody. One arm binds the AAV capsid and the other binds a receptor expressed on the target tissue. Acting as a molecular adaptor, the antibody links vector to destination. Regeneron scientists have shown in preclinical studies that such bispecific antibodies can retarget AAVs to skeletal muscle or the central nervous system with potential to facilitate crossing of the blood–brain barrier—an obstacle that has long limited neurological gene therapies.1,2

When paired with liver-detargeted capsids, the approach significantly reduced markers associated with acute liver damage in non-human primates, supporting the potential for improved tolerability. Identifying effective targeting antibodies has required extensive in vivo screening, large antibody libraries, and iterative testing. “Thorough screening in vivo provides us with the most effective targeting antibodies,” Moller-Tank noted, reflecting the complexity of biological systems that cannot be fully captured in vitro.

This antibody-guided strategy is especially promising for diseases requiring gene delivery outside the liver, including skeletal muscle disorders and central or peripheral nervous system conditions. Moller-Tank also envisions extending antibody-mediated targeting beyond AAVs to other modalities, such as small-interfering RNA (siRNA) and lipid nanoparticles, potentially creating a shared delivery logic across genetic medicines.

Rewriting retinal therapy

Ophthalmology offers one of the clearest real-world tests of antibody gene therapy. Chronic retinal diseases such as wet age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy are effectively treated with antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)—but only through frequent intravitreal injections that impose a heavy burden on patients and healthcare systems.

Surabgene lomparvovec, developed by Regenxbio in collaboration with AbbVie, seeks to eliminate that burden. The therapy uses an AAV8 vector to deliver a gene encoding an antibody fragment—a fragment antigen-binding (FAB) fragment—designed to inhibit VEGF.

Chief Scientific Officer

REGENXBIO

“A one-time gene therapy can change the treatment paradigm,” said Olivier Danos, PhD, the company’s chief scientific officer. The approach is particularly well-suited to chronic retinal diseases because the eye is relatively immune-privileged, expression can be localized, and the therapeutic target is well-validated.

Standard care requires frequent injections to preserve vision. Surabgene lomparvovec is designed to “continuously deliver an anti-VEGF FAB similar to the one used in the standard of care treatment,” Danos explained. Encouraging long-term data have propelled the therapy into late-stage trials, potentially positioning it as the first gene therapy approved for a non-rare disease.

Nanoparticles meet antibodies

In oncology, viral gene delivery faces additional hurdles, prompting interest in lipid-based nanocarriers for RNA therapeutics. Here, antibodies play yet another role—as targeting ligands decorating nanoparticle surfaces.

Sherif Ashraf Fahmy, PhD, visiting associate professor at Marburg University, and his colleagues described how antibody-functionalized lipid-based nanocarriers exploit tumor-specific receptors to improve delivery precision.3 Nanoparticles benefit from passive tumor accumulation through the enhanced permeability and retention effect, but this process is variable and often insufficient. Antibody decoration enables active targeting, thereby increasing specificity and therapeutic index.

Yet this precision introduces trade-offs. Nanocarriers typically enter cells via endocytosis, where therapeutic RNA may become trapped and degraded. Bulky antibodies can hinder endosomal escape, reducing intracellular bioavailability. Researchers are addressing this challenge by using smaller antibody formats like nanobodies and single-chain variable fragments, as well as site-specific conjugation chemistries that preserve orientation while minimizing steric interference.

Despite substantial progress, clinical translation remains challenging. Manufacturing complexity, regulatory scrutiny, and cost-effectiveness all loom large. Reported tumor accumulation varies widely depending on nanoparticle composition and antibody density, underscoring the need for systematic, head-to-head comparisons.

Programming living medicines

What unites these diverse efforts is a deeper conceptual shift: antibodies delivered by gene therapy are no longer simply drugs, but dynamic biological systems. Their behavior emerges from interactions among vectors, regulatory elements, tissue biology, and immune surveillance. Dosing becomes a matter of gene regulation rather than milligrams per kilogram. Safety becomes a function of long-term equilibrium rather than short-term exposure.

This shift has implications well beyond any single therapy. Regulators must adapt frameworks designed for transient drugs to medicines that may persist for years. Clinicians must learn to think in terms of expression control rather than dose adjustment. Patients, in turn, may come to view treatment not as a recurring event but as a one-time biological intervention with long-term consequences.

Across all four examples, antibodies are being redesigned to behave predictably in this new context. Whether encoded directly, used as targeting adaptors, expressed locally in the eye, or attached to nanoparticles, antibodies are becoming tools for biological programming. Their success will depend not only on molecular engineering, but on a systems-level understanding of how living tissues respond over time.

Managing expression over time

As antibody gene therapy matures, one of its most profound challenges is neither delivery nor efficacy, but time. Traditional antibodies exist on a pharmacological clock: after administration, they circulate, bind their targets, and are eventually cleared. Gene-encoded antibodies, by contrast, operate on a biological clock. Their presence depends on gene expression, cellular turnover, immune surveillance, and tissue-specific regulation. This temporal shift forces researchers to confront questions that conventional biologics rarely raise.

Mueller’s emphasis on durability reflects this concern. Continuous antibody expression may be beneficial when stable inhibition is required, but it also reduces flexibility. If expression is too high, toxicity may emerge slowly rather than acutely. If expression is too low, therapeutic benefit may erode over years rather than weeks. In either case, the ability to intervene is limited. As a result, Sanofi and others are increasingly focused on regulatory elements that allow expression to be dialed down, localized, or—in future iterations—switched off entirely.

Targeting strategies such as those pursued at Regeneron add another layer of temporal complexity. By redirecting viral vectors with bispecific antibodies, researchers are not merely changing where genes go, but how long they persist in different cellular environments. Muscle cells, neurons, and retinal cells differ dramatically in turnover rates and immune exposure. A vector that is stable in one tissue may behave unpredictably in another. Antibody-guided delivery therefore requires long-term studies that track expression dynamics over months and years, not just initial uptake.

The retinal gene therapy Surabgene Lomparvovec highlights both the promise and the constraint of long-term expression. Anti-VEGF therapy works precisely because VEGF signaling must be continuously suppressed. Yet, VEGF plays physiological roles in tissue maintenance and repair. Encoding an anti-VEGF FAB into ocular tissue therefore demands a careful balance between therapeutic benefit and biological restraint. The eye’s compartmentalization and immune privilege make this balance achievable, but also underscore why similar strategies may be harder to generalize systemically.

In cancer nanomedicine, time manifests as intracellular fate. As Fahmy and colleagues describe, antibody-functionalized lipid nanocarriers often succeed in reaching tumors but fail to release their RNA cargo efficiently. Endosomal trapping is not merely a spatial barrier, but a temporal one: RNA that remains sequestered too long is degraded before it can act. So, the trade-off between targeting specificity and endosomal escape determines not only where a therapy goes, but whether it functions before biological clocks run out.

Across these approaches, a shared insight is emerging. Antibody-based gene therapy is not a single intervention, but a long-term relationship between engineered molecules and living systems. Success depends on predicting how that relationship evolves over time, and on designing antibodies, vectors, and carriers that behave well not just on day one, but years later.

Redefining antibody therapy

Gene therapy will not replace antibodies. It will redefine how they are made, delivered, and sustained. As the field matures, the most important question might no longer be how potent an antibody is, but how well its expression can be controlled once the body itself becomes the factory.

In that future, medicine will move closer to biology—not by abandoning drugs, but by turning them into instructions.

Read more:

- Yip, C.W., Nguyen, T., Le Rouzic, V., et al. Retargeting of AAV using bispecific antibodies. Molecular Therapy. 32(S1):Abstract 218. (2024).

- Hadaya, L., Nguyen, T., Keating, N., et al. Retargeting of AAV to CNS using antiAAV × TFR1 bispecific antibodies. Molecular Therapy. 33(S1):Abstract 542. (2025).

- Nabih, N.W., Hassan, H.A.F.M, Preis, E., et al. Antibody-functionalized lipid nanocarriers for RNA-based cancer gene therapy: advances and challenges in targeted delivery. Nanoscale Advances. 19:5905–5931. (2025).

Mike May, PhD, is a freelance writer and editor with more than 30 years of experience. He earned an MS in biological engineering from the University of Connecticut and a PhD in neurobiology and behavior from Cornell University. He worked as an associate editor at American Scientist, and he is the author of more than 1,000 articles for clients that include GEN, Nature, Science, Scientific American, and many others. In addition, he served as the editorial director of many publications, including several Nature Outlooks and Scientific American Worldview.