Could the same principles behind deep brain stimulation—and even future AI‑guided implants—help pancreatic islet cells mature into the insulin‑producing specialists the body needs? A team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University thinks so. In a new Science study, they report that an ultrathin, flexible electronic mesh can integrate directly into developing pancreatic tissue and deliver rhythmic electrical pulses that coax stem‑cell–derived islet cells toward functional maturity. The approach, they say, may eventually point to new ways of generating functional human islets for diabetes care. The paper is titled “Implanted flexible electronics reveal principles of human islet cell electrical maturation,” and was recently published.

Diabetes, particularly type 1 diabetes, destroys the pancreatic islets that produce insulin—a hormone essential for maintaining blood‑sugar balance. Roughly two million Americans live with type 1 diabetes, and for the most severe cases, replacing lost islet cells can be life‑saving. But donor organs and islet clusters are scarce, and even when available, patients must take lifelong immunosuppressants. Lab‑grown pancreatic tissue offers an attractive alternative, yet these stem‑cell–derived islets often fail to fully mature, limiting their ability to sense glucose and release hormones with the precision of natural cells.

Juan Alvarez, PhD, senior author and assistant professor of cell and developmental biology at Penn, saw an opportunity to apply deep stimulation to the pancreas. “The words ‘bionic,’ ‘cybernetic,’ ‘cyborg,’ all of those apply to the device we’ve created,” he said. “Just like pacemakers help the heart keep rhythm, controlled electrical pulses can help pancreatic cells develop and function the way they’re supposed to.”

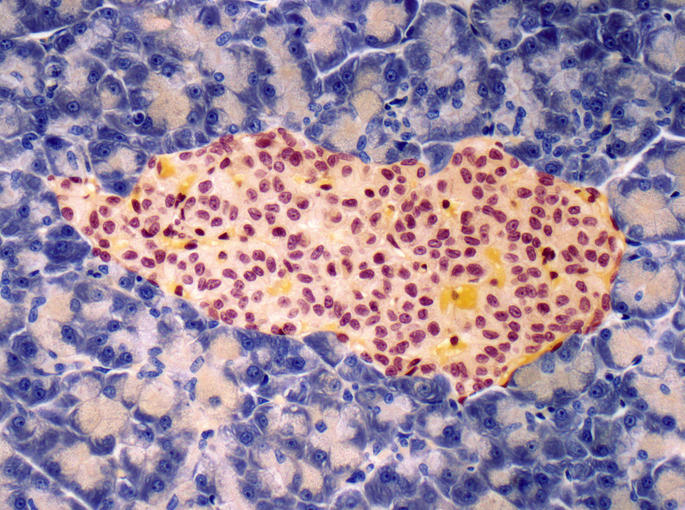

Alvarez’s lab teamed up with Jia Liu, PhD, at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, whose group specializes in tissue‑like electronic implants. Together, they embedded a stretchable mesh—thinner than a human hair—between layers of developing pancreatic cells. As the cells clustered into islets, the mesh recorded their electrical activity for two months, offering a rare, single‑cell view of how α and β cells acquire their characteristic firing patterns. The researchers then introduced a natural 24‑hour electrical rhythm, mimicking the body’s circadian cycles. “SC-α cells fired more rapid action potentials under low versus high glucose, which is consistent with glucagon secretion, whereas SC-β cells showed the opposite pattern, which is consistent with insulin release,” the authors wrote.

Alvarez described this developmental shift with a metaphor: “I like to call it when cells get their PhDs,” he said. “It is when cells stop being undecided undergrads and commit to their career path of being pancreatic or islet cells.”

The stimulation didn’t just improve individual cell behavior—it helped the cells synchronize, firing in coordinated patterns that matched their hormone‑secreting roles. That synchronization is essential for real‑world glucose control.

Looking ahead, the team sees multiple paths. Lab‑grown islet cells might be electrically “zapped” before transplantation to ensure they’re fully mature. Alternatively, the mesh could remain in place as a long‑term monitor and stimulator, preventing cells from regressing under stress. “In the future, we could have a system that runs without human intervention,” Alvarez said, envisioning AI‑driven implants that sense cellular behavior and adjust stimulation automatically.

For now, the work offers a powerful new window into islet biology—and a glimpse of how electronics and biology may merge to address diabetes in the years ahead.