It has been a tough, if interesting, year for the gene therapy space, with many ups and downs culminating in some optimism and increased funding and investment as 2025 drew to a close.

A continued financial slump in biotech investment after an all-time high in 2021, combined with financial uncertainty triggered by tariffs and inflation concerns at the beginning of Trump’s second term in January, caused the XBI biotech index, a fund that usually indicates the state of the U.S. biotech industry, to hit a pre-COVID low of $66 in April.

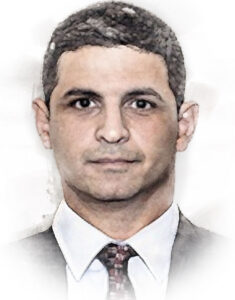

CEO

Lexeo Therapeutics

Within weeks of taking office, the new administration began cutting National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding, amounting to around $9.5 billion in cuts by June. A series of around 20,000 redundancies at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and NIH over the year also appeared to slow regulatory review and make outcomes more uncertain.

“We’ve had a lot of turnover at the senior levels in the unit of the FDA that regulates gene therapies,” agreed Nolan Townsend, CEO of Lexeo Therapeutics, a cardiology and neurology-focused genetic medicine company based in New York.

February saw Pfizer announce that it was discontinuing production of Beqvez, its hemophilia B adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based gene therapy. Despite FDA approval of the therapy in 2024, disappointing nonexistent uptake prompted the company to ditch the asset, which effectively emptied its gene therapy portfolio.

“Gene therapy is correcting a defect which will provide a lifetime cure. We get so excited about it that we forget that even then it needs to be a business proposition,” said Miguel Forte, MD, PhD, president of the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) and CEO of cell and gene therapy biotech Kiji Therapeutics. “It cannot just be a case of, ‘Because we cure the patient, everybody will line up to have it.’ It needs to still be a value proposition that makes business sense.”

CEO

Kiji Therapeutics

Other companies such as Biogen, Roche, and Vertex followed Pfizer’s example as the year progressed and either stopped or dramatically reduced their gene therapy or gene editing pipelines.

It was a bad year for Sarepta, with three deaths linked to its approved AAV therapy Elevidys for Duchenne muscular dystrophy between March and July. Rocket Pharmaceuticals also reported a therapy-associated death in a Phase II trial of its AAV-based therapy for Danon disease in May. Another AAV-linked death, albeit using a novel capsid, was reported in Capsida’s trial of its therapy for developmental and epileptic encephalopathy later in the year.

These events had a knock-on effect on investment in the sector, although towards the end of the year there were signs of improvement with some decent funding rounds, like Kriya Therapeutics’ $320 million Series D round in September and Addition Therapeutics’ $100 million Series A round in December. Pharma acquisitions, collaborations, and licensing deals with biotechs in the space also increased in the last few months of the year.

CEO

Circio

Erik Wiklund, PhD, is CEO of Circio, a Norwegian biotech with a focus on boosting AAV gene therapy efficacy using circular RNA. He believes that investors are focusing on second generation AAV therapies. “Companies are pulling out of conventional AAV,” he noted. “The ones that are doing true R&D and building the next generation therapies are doing the opposite and reinvesting into AAVs. I think Eli Lilly is a great example. They are putting significant resources into it.”

Navigating a tough funding environment

“The first half of the year was not positive for biotech. In fact, I would argue we probably hit the low point from a financing capital markets, overall valuation perspective across the biotech sector in the first half of this year,” said Townsend.

“I think gene therapy was, in particular, one of the sectors most impacted. It was the combination of a somewhat unpredictable regulator at that time for our particular part of the FDA. There was a handful of high-profile safety events that occurred around the same time frame. And while these had very specific reasons behind them … unfortunately, they impacted all companies, despite the fact that they probably should not have.”

Investment into gene therapy began to increase after FDA approvals of the ophthalmic gene therapy Luxturna and the two CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapies for blood cancer, Kymriah and Yescarta, in 2017. The number of new gene therapy trials then went up rapidly, with more than 1,300 new trials listed as ongoing or completed in a worldwide gene therapy trial database between 2017 and 2023. Overall investment in the cell and gene therapy sector, including all financing sources, also went up enormously from around $4.5 billion in 2017 to a high point of $23.1 billion in 2021.

The high in 2021 was likely assisted by the COVID-19 pandemic-associated biotech funding boom, with two mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines highlighting the value of molecular medicine to investors. However, since then, investment has been on a downward trajectory, dropping to $12.6 billion in 2022 and $11.7 billion in 2023.

Overall investment in cell and gene therapy did increase to about $15.2 billion in 2024, but estimates suggest the final number for 2025 will be significantly lower, with figures for the first three quarters of the year currently at $7.9 billion, according to the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine. The second half of the year is predicted to be better than

the first.

CEO

Treehill Partners

“I think it’s been a year of retraction, in the sense of … there’s been a lot of money, a lot of time, energy, and focus that has been put in cell and gene therapy,” said Ali Pashazadeh, MBBS, CEO of Treehill Partners, an international investment banking and strategic advisory firm focused on the healthcare sector. “I think that has, to a large extent, come to an end.”

Things were looking up towards the end of the year with new deals and strong signs of more money coming into the market, proving that not all big pharma are leaving the sector. For example, Eli Lilly acquired a number of gene therapy assets in 2025, including ophthalmic gene therapy company Adverum and its wet age-related macular degeneration AAV therapy in October and the exclusive rights to MeiraGTx’s gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis type 4 in November.

Addressing safety and regulatory concerns

The Sarepta and Rocket AAV therapy-linked deaths this year have brought some key issues with these vectors back into the spotlight.

“Part of the challenge in the gene therapy field is that it’s completely dominated by AAVs,” said Philippe Chambon, MD, PhD, CEO of Parisian biotech EG 427, which is developing a localized form of gene therapy with non-replicative herpes simplex virus 1 vectors. “We’ve seen AAVs having a mixed record with some, I would say, good progress when they are using a very local manner, such as in the ophthalmology field.”

CEO

EG 427

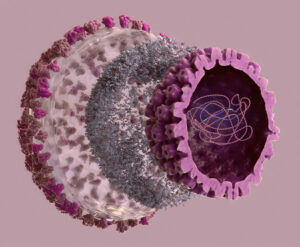

For a long time, AAVs were the only real option to make gene therapies that worked in humans and could be scaled up. However, over the last decade or so, it has become clear that there are some significant limitations that come with using these vectors.

To begin with, adenoviruses are common and many people already have immunity against AAVs, which can block them from having treatment. If people don’t already have immunity, they often develop strong anti-AAV antibodies after only one dose of therapy, making repeat dosing difficult.

AAVs can also only carry a relatively small genetic cargo in a small circular episome, meaning they are too small to be suitable for treating many genetic diseases.

“There’s a couple of challenges that episomes present,” said Michael Severino, MD, who is the CEO of Boston-based genetic medicine company Tessera Therapeutics. The company leverages target-primed reverse transcription for engineering the genome.

“First of all, they’re not terribly efficient in producing proteins, so they’re not transcribed and then ultimately translated into protein with high efficiency. So you have to use high doses, and those doses can be quite toxic in certain settings.

“The other challenge that that AAV vectors present is that these episomes are not stably integrated into the genome and don’t replicate with the host cell in the way the genome does. So if you’re trying to treat a disease where the target of interest is in a replicating cell population, that signal can be lost over time,” said Severino.

Finally, manufacturing AAVs is difficult and expensive, with quite a high amount of waste, which means that costs are driven up.

So far all the approved gene therapies, not including gene-edited therapies or CAR T-cell therapies, use AAVs, barring a few ex vivo therapies that use lentiviral vectors. For example, Krystal Biotech’s non-replicating herpes virus vector Vyjuvek for the topical treatment of the skin condition epidermolysis bullosa and the newly approved Papzimeos, Precigen’s non-replicating AAV therapy for treatment of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

There is some debate in the field about whether efforts should be focused on finding new and better ways to deliver gene therapy with different vectors, or whether the many years of AAV research should be harnessed to develop a new generation of AAV vectors that creatively manage the associated problems.

“Short term, AAV is what works,” said Wiklund. “There is nothing else that you can use at the moment that is validated in patients and can be manufactured. If you want the gene therapy quickly … the only viable strategy at the moment is AAV.”

Circio is creating a special DNA “cassette” that can be inserted into an AAV. Once inside the cell, this cassette makes circular RNA molecules that are very stable and can drive higher, longer‑lasting protein production than normal mRNA.

“For the patient, it gives you that toxicity advantage,” explained Wiklund. “Manufacturing and cost-wise this is also important because when you need to give a really high dose, it complicates the manufacturing.”

Adapting AAVs is one approach to creating next-generation therapies. Other companies such as Lexeo are using carefully chosen AAV vectors that are particularly suitable for their indications. For example, for its Friedreich’s ataxia cardiomyopathy program, Lexeo uses AAV vectors with strong heart tropism so that more of the dose goes to the myocardium and less goes to off‑target organs such as the liver.

Others in the sector, like EG 427, are developing different vectors. Non-replicating herpes virus vectors are particularly appropriate for very localized conditions on which treatment is just needed in a small area. EG 427 is using this technology to correct nerve-related diseases like overactive bladder, initially in people with pre-existing spinal injury.

“We’re seeing good progress on the non-replicative herpes front with Krystal Biotech … and with our first-in-human, Phase Ib/IIa clinical trials with our first product, where we got really strong preliminary results right out of the gate with our first cohort of patients,” said Chambon. “Now we’re at six months of data with these patients, and the efficacy profile is fully maintained.”

It was not all bad news for gene therapy in 2025, as several companies including Lexeo and EG 427 had good clinical results for their therapies. In September 2025, uniQure reported data from its pivotal Phase I/II study of its in vivo AAV‑based gene‑silencing therapy that uses an artificial microRNA to lower huntingtin production in the brain in people with Huntington’s disease. The company showed around 75% slowing of disease progression in high‑dose patients versus an external natural‑history control.

Initially hailed as very good news, uniQure was planning to seek accelerated approval in the U.S. on the back of these results. In November, they announced that the FDA was no longer open to using an external control as the main comparator and had asked for more data before approval.

“They reached an alignment with the FDA to use that Phase I study to support their Biologics License Application. However, when the leadership of the FDA changed, they actually changed their position on that,” said Townsend.

“It’s unclear whether they are going to make them run another three-year study, or if there is some version of the existing study combined with some post-approval data that will still allow the patients access to this therapy commercially next year.”

uniQure is not the only company in the sector to face frustrating changes in FDA expectations and responses this year. Ultragenyx, Rocket, and Capricor received Complete s to their Biologics License Applications in July, delaying progress of their candidate therapies due to manufacturing inspection issues rather than efficacy.

These are just a few examples, but they are not the only ones impacted. Overall, the FDA’s approach to gene therapies during the year became more demanding on safety, as problems with AAV therapies were highlighted by patient deaths, but more flexible and platform‑oriented for ultra‑rare and bespoke therapies.

Providing patients access to therapies

One of the biggest challenges is getting gene therapies to patients, even once regulators have signed off. Glybera is often cited as a warning: it became the first gene therapy approved in Europe in 2012 but was pulled from the market soon after, with just 31 patients ever receiving it.

More than ten years down the road, this is still happening with the withdrawal of Pfizer’s Beqvez, its AAV gene therapy for hemophilia B, a year after approval by the FDA. The therapy had a large price tag of $3.5 million per person and according to the company, it had no uptake from patients in the year since its approval.

Gene and cell therapies are currently expensive to manufacture, as reflected in their list prices. Improving manufacturing and making production more efficient could be one option to reduce costs.

“A lot of the technology that currently exists is developed by individual companies accessing individual manufacturers. We haven’t yet seen the group manufacturing solution, where there’s a platform paid for and then that platform is used in multiple indications,” said Pashazadeh.

“It’s not very different to the automotive industry. You see lots of incredible automotive companies that had great technologies that no longer exist. If you look back at the technology they had in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, they were probably three to four decades ahead of their time. They just hadn’t thought through commercial viability and scalability. You look at these beautiful cars, and you realize they only manufactured six of them.”

Notably, newer gene therapy developers seem to be learning lessons from the launch failures of the past. Both Townsend and Chambon say they plan to launch more affordable products onto the market, assuming they succeed in later clinical trials.

“We’ve engineered a manufacturing platform that we could envision at some point would have a cost of goods close to biologics for gene therapy,” said Townsend. “Obviously, achieving a price point in that range could give some flexibility on price so that we can access not only the U.S. and some of the large developed markets in Europe, but potentially even broader than that.”

EG 427 is taking advantage of the fact that its vector is cheaper to produce than AAVs. “It’s a standard fermentation process. We said very publicly [that] we believe that our cost of goods once we reach commercial stage will be below $1,000 a dose,” said Chambon.

In December a new company called Aradigm came out of stealth mode. It is essentially a specialized health benefits and financing platform organized as a public benefit corporation focused on cell and gene therapies. It sits between employers, health plans, and treatment centers.

Aradigm’s mission is to get more cell and gene therapies to more people by tackling the finance issue. It plans to spread the huge current cost of approved gene therapies across many employers and health plans through a shared risk pool.

“We work with purchasers, either self-insured employers or payers, and we carve out the risk for them,” explained Aradigm co-founder and CEO Will Shrank, MD.

“We charge them a premium, and we pool those premiums across all the purchasers in order to create a risk pool that offers much more stability and predictability. We have a reinsurance syndicate as a partner that creates a backstop, so we cap our purchasers’ risk at the premium, and then we pay out all the claims over the course of the year.”

By acting as the middleman, Aradigm is also planning to negotiate directly with gene therapy developers and manufacturers to get the best value for patients.

“We’re contracting directly with manufacturers for value-based deals, and we measure outcomes for our patients, even if they change employer or insurer. If pre-specified outcomes aren’t met, we claw those dollars back and return them to the pool and then back to our purchasers,” said Shrank.

“The idea there is, if you’re paying over $3 million for a therapy, and it doesn’t work, there should be some skin in the game here that we can return back to our purchasers.”

It’s early days for the company, but Shrank says there has been a lot of interest so far. Aradigm plans to launch formally with customers in mid-2026.

What to watch in 2026

After a turbulent 2025, investors and industry experts seem cautiously optimistic that 2026 will be a better year for the gene therapy sector.

“There was very significant negativity, I would say from mid-2024 to mid-2025. And then after the second half of 2025, the tide has turned,” said Wiklund. “Now there is a tailwind coming and much more positivity, triggered by both large fundraisings and pharma licensing.”

Townsend points out that many gene therapies are being developed for diseases that have no other treatments. If they succeed in clinical trials, there will automatically be a commercial demand, like uniQure’s therapy for Huntington’s disease.

“We’re beginning to see the impact that these therapies can have for patients. So I think as we see this impact occur, you will start to see pharma that comes back into gene therapy. You’ll start to see more funding for gene therapy. We just need those additional commercial successes to occur,” said Townsend.

“I personally think it would be unfortunate if the Huntington’s disease patients do not have a treatment next year,” he said. “We’ll have to keep watching how that all plays out. That’s a major one to watch in 2026.”

The sector is expanding beyond traditional AAV gene therapies, with new vectors being trialed and the gene editing space expanding, with new and innovative companies such as Tessera generating a lot of interest among investors. New readouts are expected in 2026 for things like prime editing, in vivo CRISPR, and some next generation AAV therapies.

“I think the space is continuing to mature. I think people are seeing that there can be real drugs here,” said Severino.

With a number of approval and next steps decisions expected from the FDA for gene therapies in 2026, it remains to be seen if the disruptions that resulted from staff and political changes in 2025 will continue.

“On the regulatory front, it’s hard to make predictions, but the one thing that I’ve learned in 25 years of drug discovery and development is that really good drugs change the regulatory landscape,” added Severino. “I think the regulatory landscape is going to continue to evolve, and I think highly effective therapies can really accelerate that.”

Shrank believes there will be more progress on how to make payment and patient access for existing gene therapies work better this year.

“You only really need to have experienced one $3 million claim to realize this is an important problem to take a proactive stance around,” he said. “I think the science is extraordinary, and I think there’s a clear recognition that it’s a matter of time before this becomes a really massive category. We’re starting to see that inflection point now. We’re seeing increasing use for a handful of these therapies. So there is a sense of real urgency to be proactive and build the solution in advance.”

Helen Albert is senior editor at Inside Precision Medicine and a freelance science journalist. Prior to going freelance, she was editor-in-chief at Labiotech, an English-language, digital publication based in Berlin focusing on the European biotech industry. Before moving to Germany, she worked at a range of different science and health-focused publications in London. She was editor of The Biochemist magazine and blog, but also worked as a senior reporter at Springer Nature’s medwireNews for a number of years, as well as freelancing for various international publications. She has written for New Scientist, Chemistry World, Biodesigned, The BMJ, Forbes, Science Business, Cosmos magazine, and GEN. Helen has academic degrees in genetics and anthropology, and also spent some time early in her career working at the Sanger Institute in Cambridge before deciding to move into journalism.