A study by the Molecular Oncology Research Center (CPOM) at Hospital de Amor in Barretos, Brazil, has identified distinct immune signatures in pediatric germ cell tumors (GCTs) that may guide the development of more targeted and less toxic treatments for children. Published in Frontiers in Immunology, the research analyzed the expression of about 800 immune-related genes and identified the types and behaviors of immune cells present in different GCT subtypes.

“Germ cell tumors can occur in adults as well as children and adolescents. In the pediatric population, they’re very rare, accounting for about three percent of tumors. Due to their rarity and heterogeneity, they’re difficult tumors to study,” said the study’s senior author Mariana Tomazini Pinto, PhD, a researcher of human biology at CPOM.

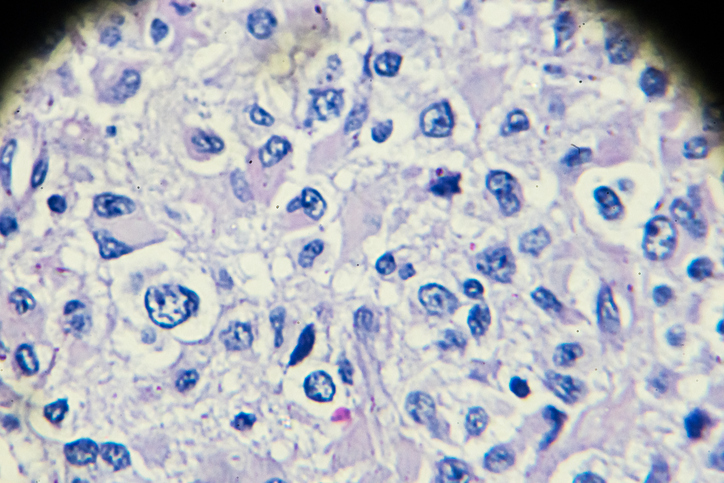

GCTs are a diverse group of cancers that originate from primordial germ cells and can arise in the ovaries, testicles, central nervous system (CNS), or retroperitoneum. Current treatments typically involve surgery to remove the tumor followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. But these standard treatments can have variable effectiveness depending on the cancer subtype and also come with long-term side effects, which a particularly pronounced in pediatric populations.

Tomazini Pinto says the researchers’ aim was to better understand the “immune environment” of GCTs, or how a patient’s immune system interacts with tumor cells. “From this analysis, we saw that different histologies have a distinct immune profile. This helps to better characterize the tumor, understand why some are more aggressive, and, at the same time, identify possible therapeutic targets. It paves the way for future studies focused on immunotherapy,” she said.

For example, the ovarian tumor dysgerminomas exhibited a relatively “immune-active” microenvironment, with high levels of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. These tumors also expressed elevated levels of immune checkpoint molecules such as CTLA4, TIGIT, and IDO1, which inhibit the immune system and have been used as targets for the development of a range of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

“This histological type, for example, had a higher number of cytotoxic T cells. This explains why it’s usually a less aggressive tumor with a good response to treatment and active defenses in the body,” Tomazini said. Based on the expression of these immune checkpoint genes, the researchers wrote, “pediatric dysgerminomas could be responsive to immunotherapies targeting multiple immune checkpoints to unlock anti-tumor immune potential.”

Contrastingly, yolk sac tumors (YSTs) showed an immunosuppressive profile, with T cells in these tumors appeared unable to mount an immune response. YSTs also showed high expression of CD24 and PVR, both of which have been linked to immune evasion and resistance to chemotherapy. “In this subtype, the defense cells recognize the tumor but are unable to act as effectively. This helps explain why YSTs are more aggressive,” Tomazini noted.

Embryonal carcinomas also expressed high levels of CD24. “YST and EC exhibited elevated levels of CD24, a molecule linked to immune evasion and chemoresistance…CD24-targeted therapies might potentiate cisplatin efficacy in pediatric GCTs, especially in resistant cases,” the researchers wrote. Prior studies have shown that blocking CD24 can re-sensitize resistant cancer cells to cisplatin, a standard chemotherapy agent.

The researchers noted that PVR, which was particularly elevated in pediatric YSTs, is increasingly recognized for its role in immune suppression and tumor progression. In other tumor types, such as pancreatic and liver cancers, PVR has been linked to worse outcomes due to its role in evading natural killer cells.

To better understand how these immune signatures differ with age, the researchers compared their pediatric cohort to existing adult GCT datasets. They found that some molecules, such as IDO1 and CD24, were consistently elevated across both age groups, while others, such as CTLA4 and PVR, varied, which points to age-specific mechanisms of immune evasion. These differences bring into focus the need for developing pediatric-specific approaches to treating pediatric GCT cancers.

“Knowing what differentiates each tumor allows us to consider personalized treatments that are more effective and less toxic for children,” Tomazini said. “This is the key issue in our study: the search for new biomarkers that can identify germ cell tumors and their subtypes in order to achieve a more accurate and specific diagnosis.”

The team’s next steps include validating these immune signatures in larger, multicenter studies and designing clinical trials to evaluate immunotherapies, particularly those targeting CD24, CTLA4, IDO1, and PVR. The researchers also noted that their findings could be the basis for developing biomarker-based diagnostics and subtype-specific treatment protocols.