Since their first descriptions in the 17th century, cells have fascinated scientists, despite being invisible to the naked eye. When virologist Joe McKellar began studying influenza viruses and cellular restriction factors during his doctoral studies at the French National Center for Scientific Research, he found himself drawn to the microscope.

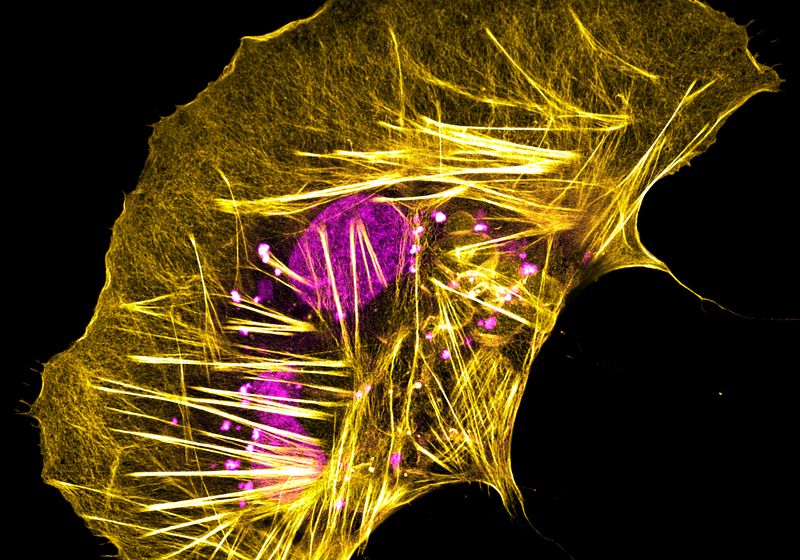

These human liver cancer cells, when grown on Poly-L-Lysine coated glass, become flattened and send out wild, spiky actin protrusions.

Joe McKellar, Institute of Molecular Genetics of Montpellier, French National Center for Scientific Research

Peering through its eyepieces, he quickly became captivated by the world of imaging. “It got me interested in everything…from confocal, super-resolution, live-imaging, all that kind of stuff.” This budding fascination grew as his postdoctoral work involved deltaviruses and provided him with access to a wide variety of unusual cell types from diverse sources, such as boa constrictors and Tasmanian devils.1

“Through working with these [cells]…you get to see that they have wild and crazy shapes,” explained McKellar. This motivated him to capture the cells’ unique features—from infiltrating viral proteins to their cytoskeleton—and share the photos on social media as a fun, artistic personal project. “Science, in itself, is kind of an art. As scientists, we are artists trying to tell a story about a biological event, function, or pathway.”

Although McKellar primarily studies deltaviruses in human, primate, and rodent cells, he also works with boa constrictor cells, thanks to collaborators who discovered the virus in snakes. 2 The image above depicts a brain-derived cell from a boa constrictor with intersecting actin fibers, shown in gold, encircling a magenta nucleus.

He investigates how to best highlight these features for imaging, either by exploring different culture conditions or identifying the compatible antibodies for staining. For this image, McKellar aimed to label what he could in the cell. The process of finding suitable antibodies that recognized reptile proteins involved a lot of trial and error; fortunately, actin worked, as it is highly conserved across species. This enabled him to showcase the dynamic network of the actin cytoskeleton in these cells.

“I hope to continue spreading the word about science and biology…[to share] how cool it is and how beautiful it can be with everybody would be the cherry on the cake.”