Staphylococcus aureus is listed as a high-priority pathogen by the World Health Organization.Credit: Dennis Kunkel Microscopy/Science Photo Library

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is projected to cause 39 million deaths worldwide over the next 25 years. But global efforts to find treatments for drug-resistant infections are not going to plan, according to two reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) released on 2 October1,2. The reports show that the global antibiotic drug-development pipeline is facing a dual crisis: a scarcity of drugs in development and a lack of innovation in methods to fight drug-resistant bacteria.

“Antimicrobial resistance is escalating, but the pipeline of new treatments and diagnostics is insufficient to tackle the spread of drug-resistant bacterial infections,” said Yukiko Nakatani, who is the WHO assistant director-general for health systems in Geneva, Switzerland, in a statement. “Without more investment in research and development (R&D), together with dedicated efforts to ensure that new and existing products reach the people who most need them, drug-resistant infections will continue to spread.”

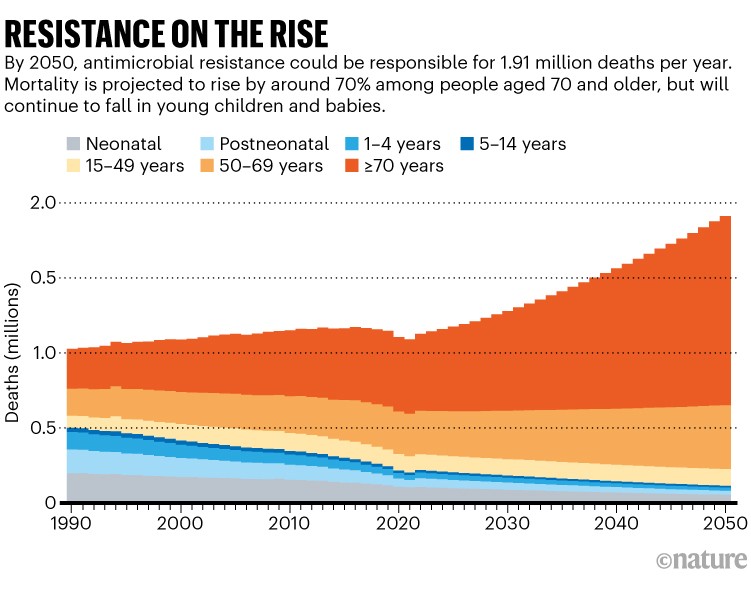

Public-health research has highlighted the extent of the AMR crisis. A report published in The Lancet3 last year found that the annual number of deaths from drug-resistant infections could increase to nearly two million by 2050, up from one million a year between 1990 and 2021. The total number of deaths attributable to AMR is predicted to rise to 1.91 million in 2050, with a further 8.22 million associated deaths (see ‘Resistance on the rise’).

“Awareness of this issue is increasing; however, it is still a silent pandemic with many deaths not being attributed to AMR,” says Rietie Venter, a microbiologist at the University of South Australia in Adelaide.

Source: Ref. 1

Too few drugs

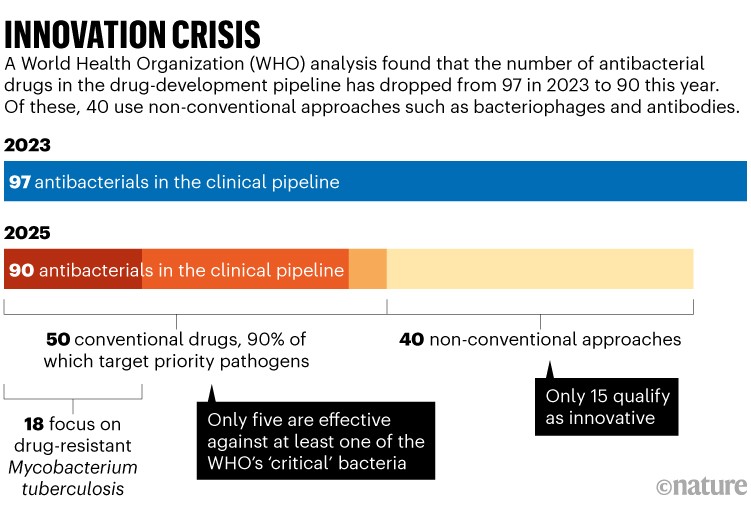

The WHO reports suggest that the world is failing to meet the United Nations’ target of reducing mortality caused by AMR by 2030 because of delays in the antibiotic drug-development pipeline. According to the analysis from the WHO, 90 antibacterial drugs are currently in development (see ‘Innovation crisis’). However, only 15 qualify as innovative — drugs that exert an additional clinically significant benefit — and only five are effective against at least one of the ‘critical bacteria’ listed on the WHO’s bacterial priority pathogen list. Since 2023, the number of antibacterial drugs in clinical-development pipelines has decreased after a WHO ruling stated that some of them were non-innovative.

The preclinical pipeline remains active, with 232 programmes across 148 groups worldwide. However, 90% of companies involved are small firms, which highlights the fragility of the R&D ecosystem, the report says. Large pharmaceutical companies have been leaving the antibiotics market for years owing to a lack of financial investment and low approval ratings of new antibiotics.

Source: go.nature.com/48evg3p

Rising infections

Even if they materialize, the development of new antibiotics still won’t be enough to curb the rise in deaths from drug-resistant infections. AMR happens when bacteria and other microorganisms evolve ways to become resistant to drugs after being exposed to them, meaning drug makers have to play a constant cat-and-mouse game of creating new antibiotics to overcome evolving resistance.

Ultimately, the misuse and overuse of antimicrobial drugs in human medicine and agriculture are the main drivers of AMR, which is why cuts to antibiotic usage are needed to reduce drug-resistant infections, alongside new antibiotic therapies. Gwen Knight and Kathryn Holt, who are co-directors of the AMR Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, say that there are insufficient data to know the relative importance of livestock versus human antibiotic use in driving AMR.

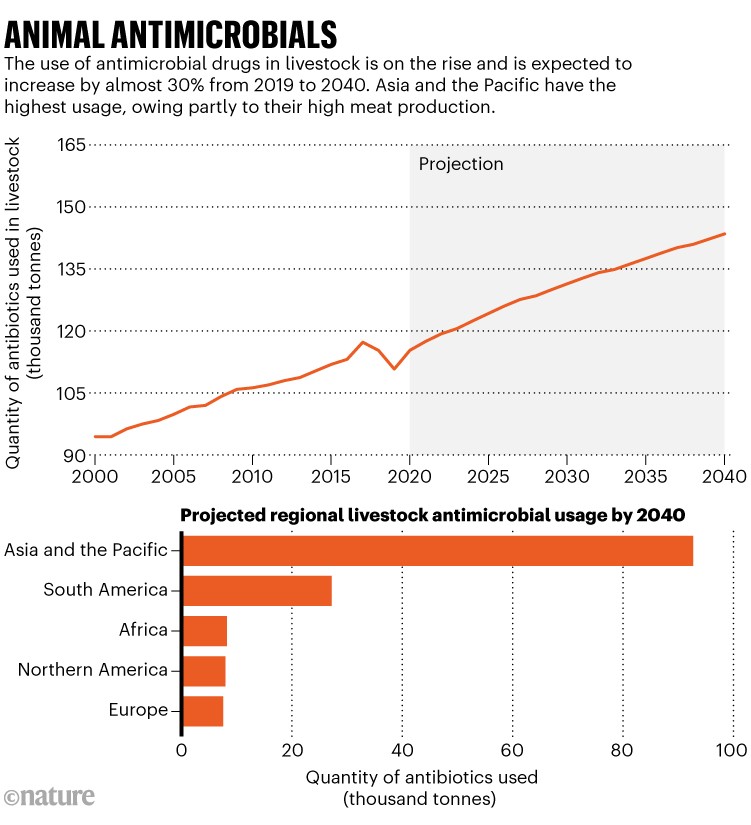

World leaders have committed to cutting the global use of antibiotics to reduce AMR-related deaths by 10% by 2030. However, the pledge doesn’t look likely to succeed, because projections suggest that antibiotic use in both humans and livestock will increase in the years ahead (see ‘Animal antimicrobials’). “We cannot prevent the development of AMR, but we can implement measures to slow it down, and currently, we are not super successful with this,” says Venter.

Source: Ref. 3

Reducing antibiotic use in livestock is a priority, because it represents 73% of global sales of a range of antimicrobial agents4. Annual antibiotic use in livestock has increased in the past few decades and, despite pledges to reduce it, is projected to increase by almost 30% by 2040 from a 2019 baseline5. The rise is due to increasing demand for meat in developing regions, especially in countries such as China and Thailand. In Asia, meat production has increased 15-fold since 1961, way above the global average of a 4-fold increase.

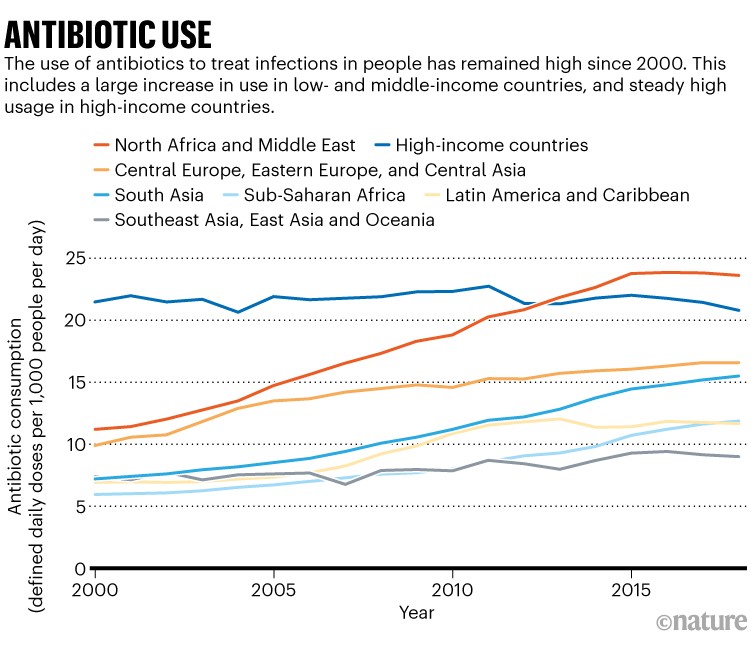

Antibiotic use in human health-care has also remained high since 20006, and is increasing in countries that do not have access to high-quality health-care infrastructure, which contributes to inappropriate antibiotic use (see ‘Antibiotic use’).

Source: Ref. 4

Priority pathogens

In 2024, the WHO published its bacterial priority pathogen list, which highlights drug-resistant bacteria on the basis of their threat level to public health (see ‘Priority bacteria’). Many of the deadliest infections are caused by a group of bacteria with particularly strong drug resistance, called gram-negative bacteria. This category includes Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter baumannii — a pathogen associated with hospital-acquired infections. Only five of the antibacterials currently in the drug-development pipeline are effective against these priority bacteria.